Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 12:34 — 12.6MB)

This week we’re going to learn about some armored dinosaurs, a suggestion by Damian!

I love that there’s a stock picture of an ankylosaurus:

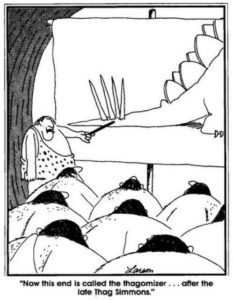

Stegosaurus displaying its thagomizer:

Thagomizer explained:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

This week’s episode is another suggestion, this one from Damian, who wants to learn about armored dinosaurs like stegosaurus. It turns out that stegosaurus and its relatives are really interesting, so thanks to Damian for the suggestion!

We’ll start with ankylosaurus, which lived near the end of the Cretaceous period, right before all the non-avian dinosaurs went extinct, about 65 million years ago. A lot of paleontologists pronounce it ANKillosaurus, but it’s properly pronounced anKYlosaurus and for once, I’m finding the correct pronunciation easier, probably because it has the name Kylo right in the middle, like Kylo Ren of Star Wars.

There are a lot of species in the ankylosauridae family, but ankylosaurus was the biggest and is probably the one you would recognize since it’s a popular dinosaur. It’s the one with a big club on the end of its tail, but its leathery skin was studded with armored plates called osteoderms or scutes that made it look something like a modern crocodile. It also had spikes along its sides, although they weren’t as long or as impressive as some of the other ankylosaurids’ spikes.

We don’t know exactly how big ankylosaurus could get because we’re still missing some key bones like the pelvis, but paleontologists estimate it could grow around 33 feet long, or ten meters. Is legs were relatively short and its body wide, something like a turtle. When it felt threatened, it may have just dropped to the ground to protect its unarmored belly and laid there like a huge spiky tank.

Because we only have a few fossil specimens of ankylosaurus, there’s actually a lot we don’t know about it. Much of what we do know is actually mostly from ankylosaurus relatives. Researchers think ankylosaurus actually may not have been a typical ankylosaurid. They aren’t sure if the few fossils found mean it was a rare animal or if it just lived inland, away from water, since fossilization is much more common when water is involved. It lived in what is now North America, although it had relatives that lived throughout much of the world.

Ankylosaurus had a beak something like a turtle’s but it also had teeth that it probably used to strip leaves from stems before swallowing them whole. It probably ate ferns and low-growing shrubs. It had a massive gut where plant material would have been fermented and broken down in what was probably a long digestive process. But some researchers think it may have mostly eaten grubs, worms, and roots that it dug up with its powerful forelegs or its beak, sort of like a rooting hog. Its nostrils are smaller and higher on its nose than in other ankylosaurids, which could be an adaptation to keep dirt out. This might also explain why ankylosaurus appears different from other ankylosaurids, which definitely ate plants.

Ankylosaurus had a remarkably small brain for its size. Paleontologists think it may have used its massive tail club as a defensive weapon, but they don’t know for sure. The tail might just have been for display, or maybe males used their tail clubs to fight during mating season. It probably couldn’t walk very fast and was probably cold-blooded, which allowed it to survive after other dinosaurs went extinct after the big meteor struck. Eventually the plants it ate started going extinct, and since it was a big animal that needed a lot of food, it finally went extinct too. Researchers think bird ancestors survived because they were small and could live by eating plant seeds.

One interesting thing about ankylosaurs of all kinds is how they kept from overheating. Large bodies retain heat better than small bodies, which is why polar bears and mammoths are such chonks. Ankylosaurs were massive animals that lived in warm climates. New research published in late 2018 shows that they kept their brains cool by having extremely convoluted nasal passages with blood vessels alongside them. This helped cool the blood before it reached the brain, keeping it from overheating.

Ankylosaurus was related to stegosaurus. Stegasaurus lived in North America around 150 million years ago, during the Jurassic, but its ancestors were found in many other parts of the world. Like its cousin, stegosaurus had a small brain but grew to enormous size, as much as 30 feet long, or 9 meters. You definitely know what a stegosaurus looks like, since next to T rex it’s probably the most recognizable dinosaur. It had big dermal plates that stood up in rows along its spine and four spikes on the end of its tail, called a thagomizer. I’m not even making that name up, it really is called a thagomizer and the term really is from the Far Side cartoon. Its forelegs were shorter than its hind legs, and researchers think it probably stood with its head down to browse on low-growing vegetation, with its tail sticking up as a warning to any predator foolish enough to get too close.

The thagomizer spikes were probably used for defense. Not only do a lot of the spikes show injuries, we have a fossilized tail vertebra from an Allosaurus with a hole punched right through it. The hole matches the size and shape of a stegosaurus’s tail spike.

Paleontologists aren’t as sure about what the plates were for. They were made of bone covered with a keratin sheath that might have been brightly colored or patterned. There are signs that the plates contained a lot of blood vessels for their size, which suggests they helped with thermoregulation—that is, they might have helped the animal absorb and shed heat. Then again, new studies also suggest that the males had larger, broader plates while females had smaller, sharper ones. This argues that the plates might have been for display. Of course, they could be for both display and for thermoregulation.

Sometimes you’ll hear that stegosaurus had such a small brain that it had a second brain in the hip to help it control its tail. This isn’t the case, though. There is a canal in the stegosaurus’s hip near the spinal cord, but this is something found in other dinosaurs and in modern birds. In birds it’s where a structure called the glycogen body is, but researchers don’t actually know what the glycogen body is for. That’s right, something present in all birds, even chickens and pigeons, is more or less still a mystery to scientists. But whatever it is, it’s not a second brain.

There are other mysteries associated with the stegosaurus, like how it ate. It had a tiny head for its size, about the size of a dog’s head, with peglike teeth that seem to have been used for chewing or shearing plant material. But because the head was so small, and the teeth weren’t shaped for grinding, it probably couldn’t have chewed its food up like modern grazing mammals do. But it also doesn’t seem to have ingested gastroliths, small stones used for grinding up food in the stomach.

There were lots of other armored dinosaurs, generally related to stegosaurus and ankylosaurus. I was going to talk about triceratops too, but technically it didn’t have armor, just head frills and horns. Besides, I think triceratops and its relations need their own episode pretty soon. So we’ll finish up with another ankylosaurid, Akainacephalus.

The only fossil we have of akainacephalus was discovered in 2008 in Utah. It’s a remarkably complete fossil, including the skull and jaws, and has been dated to around 76 million years old. It had a spiky ridge over its eyes and short triangular horns on its cheeks that pointed downward. It also had a tail club that ankylosaurids are known for.

Akainacephalus was formally described in 2018 as not just a new species of ankylosaurid, but one in its own genus. Even though it was found in North America, researchers have determined that it’s more closely related to the ankylosaurids that lived in Asia.

Before Akainacephalus evolved, Asia and North America were connected with a land bridge due to low sea levels. This land bridge is called Beringia, and while it’s currently underwater, at different times in the past it’s been exposed and allowed animals to cross from Asia to North America and from North America to Asia. Beringia is about 600 miles wide, or around 1,000 km, when it’s above water. At the moment, it’s represented by a couple of little islands in the shallow Bering Strait, since it’s been underwater for the last 11,000 years.

Previously researchers thought this land bridge had only been open once during the Cretaceous, but that was before paleontologists examined akainacephalus. Since akainacephalus is related to ankylosaurids that lived in Asia after the land bridge was submerged, it’s possible there was a second opening of Beringia that allowed akainacephalus’s ancestor to migrate from Asia to North America.

That’s one of the really neat things about science. You start by looking at a cool spiky fossil skull, and you end up learning something new about how deep the oceans were 80-some million years ago.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast online at strangeanimalspodcast.com. We’re on Twitter at strangebeasties and have a facebook page at facebook.com/strangeanimalspodcast. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. We also have a Patreon if you’d like to support us that way.

Thanks for listening!