Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 20:41 — 22.9MB)

Subscribe: | More

Here’s the big invertebrate episode I’ve been promising people! Thanks to Sam, warbrlwatchr, Jayson, Richard from NC, Holly, Kabir, Stewie, Thaddeus, and Trech for their suggestions this week!

Further reading:

Does the Spiral Siphonophore Reign as the Longest Animal in the World?

The common nawab butterfly:

The common nawab caterpillar:

A velvet worm:

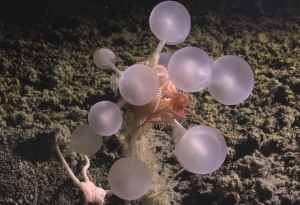

A giant siphonophore [photo by Catriona Munro, Stefan Siebert, Felipe Zapata, Mark Howison, Alejandro Damian-Serrano, Samuel H. Church, Freya E.Goetz, Philip R. Pugh, Steven H.D.Haddock, Casey W.Dunn – https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1055790318300460#f0030]:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

Hello to 2026! This is usually where I announce that I’m going to do a series of themed episodes throughout the coming year, and usually I forget all about it after a few months. This year I have a different announcement. After our nine-year anniversary next month, which is episode 470, instead of new episodes I’m going to be switching to old Patreon episodes. I closed the Patreon permanently at the end of December but all the best episodes will now run in the main feed until our ten-year anniversary in February 2027. That’s episode 523, when we’ll have a big new episode that will also be the very last one ever.

I thought this was the best way to close out the podcast instead of just stopping one day. The only problem is the big list of suggestions. During January I’m going to cover as many suggestions as I possibly can. This week’s episode is about invertebrates, and in the next few weeks we’ll have an episode about mammals, one about reptiles and birds, and one about amphibians and fish, although I don’t know what order they’ll be in yet. Episode 470 will be about animals discovered in 2025, along with some corrections and updates.

I hope no one is sad about the podcast ending! You have a whole year to get used to it, and the old episodes will remain forever on the website so you can listen whenever you like.

All that out of the way, let’s start 2026 right with a whole lot of invertebrates! Thanks to Sam, warbrlwatchr, Jayson, Richard from NC, Holly, Kabir, Stewie, Thaddeus, and Trech for their suggestions this week!

Let’s start with Trech’s suggestion, a humble ant called the weaver ant. It’s also called the green ant even though not all species are green, because a species found in Australia is partially green. Most species are red, brown, or yellowish, and they’re found in parts of northern and western Australia, southern Asia, and on most islands in between the two areas, and in parts of central Africa. The weaver ant lives in trees in tropical areas, and gets the name weaver ant because of the way it makes its nest.

The nests are made out of leaves, but the leaves are still growing on the tree. Worker ants grab the edge of a leaf in their mandibles, then pull the leaf toward another leaf or sometimes double the leaf over. Sometimes ants have to make a chain to reach another leaf, with each ant grabbing the next ant around the middle until the ant at the end of the chain can grab the edge of a leaf. While the leaf is being pulled into place alongside the edge of another leaf, or the opposite edge of the same leaf, other workers bring larvae from an established part of the nest. The larvae secrete silk to make cocoons, but a worker ant holds a larva at the edge of the leaf, taps its little head, and the larva secretes silk that the workers use to bind the leaf edges together. A single colony has multiple nests, often in more than one tree, and are constantly constructing new ones as the old leaves are damaged by weather or just die off naturally.

The weaver ant mainly eats insects, which is good for the trees because many of the insects the ants kill and eat are ones that can damage trees. This is one reason why farmers in some places like seeing weaver ants, especially fruit farmers, and sometimes farmers will even buy a weaver ant colony starter pack to place in their trees deliberately. The farmer doesn’t have to use pesticides, and the weaver ants even cause some fruit- and leaf-eating animals to stay away, because the ants can give a painful bite. People in many areas also eat the weaver ant larvae, which is considered a delicacy.

Our next suggestion is by Holly, the zombie snail. I actually covered this in a Patreon episode, but I didn’t schedule it for next year because I thought I’d used the information already in a regular episode, but now I can’t find it. So let’s talk about it now!

In August of 2019, hikers in Taiwan came across a snail that looked like it was on its way to a rave. It had what looked like flashing neon decorations in its head, pulsing in green and orange. Strobing colors are just not something you’d expect to find on an animal, or if you did it would be a deep-sea animal. The situation is not good for the snail, let me tell you. It’s due to a parasitic flatworm called the green-banded broodsac.

The flatworm infects birds, but to get into the bird, first it has to get into a snail. To get into a snail, it has to be in a bird, though, because it lives in the cloaca of a bird and attaches its eggs to the bird’s droppings. When a snail eats a yummy bird dropping, it also eats the eggs. The eggs hatch in the snail’s body instead of being digested, where eventually they develop into sporocysts. That’s a branched structure that spreads throughout the snail’s body, including into its head and eyestalks.

The sporocyst branches that are in the snail’s eyestalks further develop into broodsacs, which look like little worms or caterpillars banded with green and orange or green and yellow, sometimes with black or brown bands too—it depends on the species. About the time the broodsacs are ready for the next stage of life, the parasite takes control of the snail’s brain. The snail goes out in daylight and sits somewhere conspicuous, and its body, or sometimes just its head or eyestalks, becomes semi-translucent so that the broodsacs show through it. Then the broodsacs swell up and start to pulse.

The colors and movement resemble a caterpillar enough that it attracts birds that eat caterpillars. A bird will fly up, grab what it thinks is a caterpillar, and eat it up. The broodsac develops into a mature flatworm in the bird’s digestive system, and sticks itself to the walls of the cloaca with two suckers, and the whole process starts again.

The snail gets the worst part of this bargain, naturally, but it doesn’t necessarily die. It can survive for a year or more even with the parasite living in it, and it can still use its eyes. When it’s bird time, the bird isn’t interested in the snail itself. It just wants what it thinks is a caterpillar, and a lot of times it just snips the broodsac out of the snail’s eyestalk without doing a lot of damage to the snail.

If a bird doesn’t show up right away, sometimes the broodsac will burst out of the eyestalk anyway. It can survive for up to an hour outside the snail and continues to pulsate, so it will sometimes still get eaten by a bird.

Okay, that was disgusting. Let’s move on quickly to the tiger beetle, suggested by both Sam and warblrwatchr.

There are thousands of tiger beetle species known and they live all over the world, except for Antarctica. Because there are so many different species in so many different habitats, they don’t all look the same, but many common species are reddish-orange with black stripes, which is where the name tiger beetle comes from. Others are plain black or gray, shiny blue, dark or pale brown, spotted, mottled, iridescent, bumpy, plain, bulky, or lightly built. They vary a lot, but one thing they all share are long legs.

That’s because the tiger beetle is famous for its running speed. Not all species can fly, but even in the ones that can, its wings are small and it can’t fly far. But it can run so fast that scientists have discovered that its simple eyes can’t gather enough photons for the brain to process an image of its surroundings while it runs. That’s why the beetle will run extremely fast, then stop for a moment before running again. Its brain needs a moment to catch up.

The tiger beetle eats insects and other small animals, which it runs after to catch. The fastest species known lives around the shores of Lake Eyre in South Australia, Rivacindela hudsoni. It grows around 20 mm long, and can run as much as 5.6 mph, or 9 km/hour, not that it’s going to be running for an entire hour at a time. Still, that’s incredibly fast for something with little teeny legs.

Another insect that is really fast is called the common nawab, suggested by Jayson. It’s a butterfly that lives in tropical forests and rainforests in South Asia and many islands. Its wings are mainly brown or black with a big yellow or greenish spot in the middle and some little white spots along the edges, and the hind wings have two little tails that look like spikes. It’s really pretty and has a wingspan more than three inches across, or about 8.5 cm.

The common nawab spends most of its time in the forest canopy, flying quickly from flower to flower. Females will travel long distances, but when a female is ready to lay her eggs, she returns to where she hatched. The male stays in his territory, and will chase away other common nawab males if they approach.

The common nawab caterpillar is green with pale yellow stripes, and it has four horn-like projections on its head, which is why it’s called the dragon-headed caterpillar. It’s really awesome-looking and I put it on the list to cover years ago, then forgot it until Jayson recommended it. But it turns out there’s not a lot known about the common nawab, so there’s not a lot to say about it.

Next, Richard from NC suggested the velvet worm. It’s not a worm and it’s not made of velvet, although its body is soft and velvety to the touch. It’s long and fairly thin, sort of like a caterpillar in shape but with lots of stubby little legs. There are hundreds of species known in two families. Most species of velvet worm are found in South America and Australia.

Some species of velvet worm can grow up to 8 and a half inches long, or 22 cm, but most are much smaller. The smallest lives in New Zealand on the South Island, and only grows up to 10 mm long, with 13 pairs of legs. The largest lives in Costa Rica in Central America and was only discovered in 2010. It has up to 41 pairs of legs, although males only have 34 pairs.

Various species of velvet worm are different colors, although a lot of them are reddish, brown, or orangey-brown. Most species have simple eyes, although some have no eyes at all. Its legs are stubby, hollow, and very simple, with a pair of tiny chitin claws at the ends. The claws are retractable and help it climb around. It likes humid, dark places like mossy rocks, leaf litter, fallen logs, caves, and similar habitats. Some species are solitary but others live in social groups of closely related individuals.

The velvet worm is an ambush predator, and it hunts in a really weird way. It’s nocturnal and its eyes are not only very simple, but the velvet worm can’t even see ahead of it because its eyes are behind a pair of fleshy antennae that it uses to feel its way delicately forward. It walks so softly on its little legs that the small insects and other invertebrates that it preys on often don’t even notice it. When it comes across an animal, it uses its antennae to very carefully touch it and decide whether it’s worth attacking.

When it decides to attack, it squirts slime that acts like glue. It has a gland on either side of its head that squirts slime quite accurately. Once the prey is immobilized, the velvet worm may give smaller squirts of slime at dangerous parts, like the fangs of spiders. Then it punctures the body of its prey with its jaws and injects saliva, which kills the animal and starts to liquefy its insides. While the velvet worm is waiting for this to happen, it eats up its slime to reuse it, then sucks the liquid out of the prey. This can take a long time depending on the size of the animal—more than an hour.

A huge number of invertebrates, including all insects and crustaceans, are arthropods, and velvet worms look like they should belong to the phylum Arthropoda. But arthropods always have jointed legs. Velvet worm legs don’t have joints.

Velvet worms aren’t arthropods, although they’re closely related. A modern-day velvet worm looks surprisingly like an animal that lived half a billion years ago, Antennacanthopodia, although it lived in the ocean and all velvet worms live on land. Scientists think that the velvet worm’s closest living relative is a very small invertebrate called the tardigrade, or water bear, which is Stewie’s suggestion.

The water bear isn’t a bear but a tiny eight-legged animal that barely ever grows larger than 1.5 millimeters. Some species are microscopic. There are about 1,300 known species of water bear and they all look pretty similar, like a plump eight-legged stuffed animal with a tubular mouth that looks a little like a pig’s snout. It uses six of its fat little legs for walking and the hind two to cling to the moss and other plant material where it lives. Each leg has four to eight long hooked claws. Like the velvet worm, the tardigrade’s legs don’t have joints. They can bend wherever they want.

Tardigrades have the reputation of being extremophiles, able to withstand incredible heat, cold, radiation, space, and anything else scientists can think of. In reality, it’s just a little guy that mostly lives in moss and eats tiny animals or plant material. It is tough, and some species can indeed withstand extreme heat, cold, and so forth, but only for short amounts of time.

The tardigrade’s success is mainly due to its ability to suspend its metabolism, during which time the water in its body is replaced with a type of protein that protects its cells from damage. It retracts its legs and rearranges its internal organs so it can curl up into a teeny barrel shape, at which point it’s called a tun. It needs a moist environment, and if its environment dries out too much, the water bear will automatically go into this suspended state, called cryptobiosis. When conditions improve, the tardigrade returns to normal.

Another animal has a similar ability, and it’s a suggestion by Thaddeus, the immortal jellyfish. It’s barely more than 4 mm across as an adult, and lives throughout much of the world’s oceans, especially where it’s warm. It eats tiny food, including plankton and fish eggs, which it grabs with its tiny tentacles. Small as it is, the immortal jellyfish has stinging cells in its tentacles. It’s mostly transparent, although its stomach is red and an adult jelly has up to 90 white tentacles.

The immortal jellyfish starts life as a larva called a planula, which can swim, but when it finds a place it likes, it sticks itself to a rock or shell, or just onto the sea floor. There it develops into a polyp colony, and this colony buds new polyps that are clones of the original. These polyps swim away and grow into jellyfish, which spawn and develop eggs, and those eggs hatch into new planulae.

Polyps can live for years, while adult jellies, called medusae, usually only live a few months. But if an adult immortal jellyfish is injured, starving, sick, or otherwise under stress, it can transform back into a polyp. It forms a new polyp colony and buds clones of itself that then grow into adult jellies.

It’s the only organism known that can revert to an earlier stage of life after reaching sexual maturity–but only an individual at the adult stage, called the medusa stage, can revert to an earlier stage of development, and an individual can only achieve the medusa stage once after it buds from the polyp colony. If it reverts to the polyp stage, it will remain a polyp until it eventually dies, so it’s not really immortal but it’s still very cool.

All the animals we’ve talked about today have been quite small. Let’s finish with a suggestion from Kabir, a deep-sea animal that’s really big! It’s the giant siphonophore, Praya dubia, which lives in cold ocean water around many parts of the world. It’s one of the longest creatures known to exist, but it’s not a single animal. Each siphonophore is a colony of tiny animals called zooids, all clones although they perform different functions so the whole colony can thrive. Some zooids help the colony swim, while others have tiny tentacles that grab prey, and others digest the food and disperse the nutrients to the zooids around it.

Some siphonophores are small but some can grow quite large. The Portuguese man o’ war, which looks like a floating jellyfish, is actually a type of siphonophore. Its stinging tentacles can be 100 feet long, or 30 m. Other siphonophores are long, transparent, gelatinous strings that float through the depths of the sea, and that’s the kind the giant siphonophore is.

The giant siphonophore can definitely grow longer than 160 feet, or 50 meters, and may grow considerably longer. Siphonophores are delicate, and if they get washed too close to shore or the surface, waves and currents can tear them into pieces. Other than that, and maybe the occasional whale or big fish swimming right through them and breaking them up, there’s really no reason why a siphonophore can’t just keep on growing and growing and growing…

You can find Strange Animals Podcast at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, corrections, or suggestions, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com.

Thanks for listening!

_Nemichthys_scolopaceus_2-300x300.jpg)