Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 11:32 — 11.7MB)

Show transcript:

Hi. If you’re hearing this, it means I’m sick or something else has happened that has kept me from making a new episode this week. This was a Patreon bonus episode from mid-August 2019. I think it’s a good one. If you’re a Patreon subscriber, I’m sorry you don’t have a new episode to listen to this time. Hopefully I’ll be feeling better soon and we can get back to learning about lots of strange animals.

Welcome to the Patreon bonus episode of Strange Animals Podcast for mid-August, 2019!

While I was doing research for the paleontology mistakes and frauds episodes, I came across the discovery of what might have been the biggest land animal that ever lived. But while I wanted to include it in one episode or the other, it wasn’t clear that it was either a mistake or a fraud. It might in fact have been a real discovery, now lost.

In late 1877 or early 1878, a man named Oramel Lucas was digging up dinosaur bones for the famous paleontologist Edward Cope. Cope was one of the men we talked about in the paleontological mistakes episode, the bitter enemy of Othniel Marsh. Lucas directed a team of workers digging for fossils in a number of sites near Garden Park in Colorado, and around the summer of 1878 he shipped the fossils he’d found to Marsh. Among them was a partial neural arch of a sauropod.

The neural arch is the top part of a vertebra, in this case probably one near the hip. Sauropods, of course, are the biggest land animals known. Brontosaurus, Apatosaurus, and Diplodocus are all sauropods. Sauropods had long necks that were probably mostly held horizontally as the animal cropped low-growing plants and shrubs, and extremely long tails held off the ground. Their legs were column-like, something like enormous elephant legs, to support the massively heavy body.

We know what Diplodocus looked like because we have lots of Diplodocus fossils and can reconstruct the entire skeleton, but for most other sauropods we still only have partial skeletons. The body size and shape of other sauropods are conjecture based on what we know about Diplodocus. In some cases we only have a few bones, or in the case of Cope’s 1878 sauropod, a single partial bone.

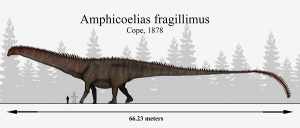

Cope examined the neural arch, sketched it and made notes, and published a formal description of it later in 1878. He named it Amphicoelias [Am-fi-sil-i-as] fragillimus.

The largest species of Diplodocus, D. hallorum, was about 108 feet long, or 33 meters, measuring from its stretched-out head to the tip of its tail. Estimates of fragillimus from Cope’s measurement of the single neural arch suggest that its tail alone might be longer than Diplodocus’s whole body.

Cope measured fragillimus’s partial neural arch as 1.5 meters tall, or almost five feet. That’s only the part that remained. It was broken and weathered, but the entire vertebra may have been as large as 2.7 meters high, or 8.85 feet. From that measurement, and considering that fragillimus was seemingly related to Diplodocus, even the most conservative estimate of fragillimus’s overall size is 40 meters long, or 131 feet, and could be as long as 60 meters, or 197 feet. This is far larger than even Seismosaurus, which is estimated to have grown 33.5 meters long, or 110 feet, and which is considered the largest land animal known.

So why isn’t fragillimus considered the largest land animal known? Mainly because we no longer have the fossil to study. It’s completely gone with no indication of where it might be or what happened to it. And that has led to some people thinking that it either never existed in the first place, or that Cope measured it wrong.

One argument is that Cope wrote down the measurements wrong and that the neural arch wasn’t nearly as large as Cope’s notes indicate. But Lucas, who collected the fossil, always made his own measurements and these match up with what Cope reported. Lucas and Cope both remarked on the size of the fossil, which was far larger than any they had ever found.

Oddly, Cope’s nemesis Marsh inadvertently vouches for him by the things Marsh didn’t do. We know that Marsh kept tabs on Cope, including even paying people to spy on his fossil excavations. Marsh was also always ready to pounce on any of Cope’s mistakes and make them a big deal. But Marsh never said anything about the neural arch not being a real find, and never questioned Cope’s measurements of it.

Cope never mentioned what happened to the fossil. It wasn’t until 1921 that two researchers pointed out that it was missing from the Cope Collection. So what happened to it?

Most researchers suspect it just crumbled away. The fossil formed in a type of rock called mudstone, which fractures easily into little irregular cubes. In fact, Cope gave the sauropod the name fragillimus because the fossil appeared so fragile—not because of the mudstone per se, but because so much of the fossil had already weathered away and as a result it looked too delicate to be part of such a large animal.

These days paleontologists treat fossils with various preservatives to harden them, but that practice didn’t start until 1880, several years after the neural arch was found. Cope only made one drawing of it, which wasn’t his usual practice. It’s possible the fossil was so delicate at that point that just turning it over to draw the other side caused it to fall apart. Many researchers suspect that Cope or one of his assistants eventually discarded it after it crumbled into a pile of mudstone blocks.

Obviously, if we don’t have the fossil Cope examined, maybe we should go looking for more fossils that Cope’s workers might have missed. Cope did mention a femur located near the neural arch that may have been another fragillimus bone, but it’s not clear if the femur was actually collected. We have Cope’s journal entry where he sketched the dig sites Lucas was working, a rough map that shows at least seven sites. But it’s been a century and a half since then and most of the sites have been lost. In 1994 a team tried to relocate the site where Lucas found the neural arch, but without luck. It’s also possible that any remaining fossils have weathered away completely. In the dig sites that have been found, the mudstone has mostly weathered away down to the underlying sandstone.

Researchers have been able to estimate a probable age for fragillimus from Cope’s notes about the stratigraphy where the neural arch was found. Fragillimus probably lived in the late Jurassic, roughly 150 million years ago. This matches up with the age of other enormously large sauropods. But if fragillimus really was so much larger than the others, how did it live? Would an animal that size actually be able to support its weight, feed itself, and function overall? Wouldn’t it overheat in the sun or starve due to not finding enough food to power its colossal body?

Researchers think that sauropods grew to such enormous sizes because their food was nutritionally lacking. That doesn’t make sense until you realize that when a herbivore’s food is poor, the longer it can keep the plant material in its digestive system, the more nutrients it can extract from it. Sauropods were probably hindgut fermenters like all modern herbivorous reptiles and a lot of birds. The best way to keep lots of plant material in the digestive system is to be really big and have a really big digestive tract. This is the case with many herbivores today, like elephants, rhinos, and horses. Other benefits come from being extremely large, too, such as being larger than potential predators.

Sauropods generally lived in semiarid savannas. Grass hadn’t evolved yet, so researchers think the main groundcover plant was ferns, which sauropods probably ate in bulk. There would also have been shrubs, small trees, and some areas with much taller trees. It’s possible that sauropods spent most of the day among the trees, sleeping in the shade, and came out at night to do most of their grazing.

Cope also found fossils from another sauropod that he named Amphicoelias altus. In fact, he described both Amphicoelias species in the same paper. Some researchers have therefore suspected that the two species were actually the same. A. altus is estimated to grow about the same size as Diplodocus, about 82 feet long, or 25 meters.

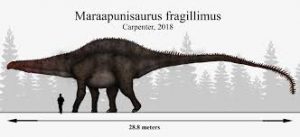

But in 2018, a paleontologist named Kenneth Carpenter examined Cope’s information on fragillimus and came to some interesting conclusions. He reclassified it from the family Diplodocidae to the family Rebbachisauridae and renamed it Maraapunisaurus fragillimus. As a result, the estimates of its size have changed. Carpenter suggests that it was much smaller, about 99 feet long, or 30 meters, but that Cope’s measurements were correct. Sauropods of this family just have larger vertebrae than Diplodocidae.

The only difficulty with fragillimus being a member of the Rebbachisauridae is that this group of sauropods isn’t known to have lived in North America, just Europe and South America. But the fossil record is incomplete and every find requires researchers to adjust what we know about where dinosaurs lived and how widespread a particular species or family was.

Hopefully, eventually more and better remains of fragillimus will turn up soon. Then we can work out exactly how big it really was.

Thanks for your support, and thanks for listening! The next episode in the main feed will be about an unusual small fish and an extinct pig relative called the unicorn pig. Basically both those animals should have gone in other episodes but I messed up and forgot to add them to strangest small fish and the weird pigs episodes, but they’re both really neat and I wanted to share them.

https://www.patreon.com/rss/strangeanimalspodcast?auth=eb94e995bdf4bc11930eeda8bc5b4a3e