Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 10:02 — 10.0MB)

This week let’s find out what has paleontologists so excited about this dinosaur!

Further reading:

The Nature article that kicked this all off (you can only read the abstract for free but it’s full of good information)

Paleontologist Who Uncovered Prehistoric River Monster’s Tail Explains Why It’s Such a Game Changer (Newsweek)

Further watching:

A good video about the new findings

Spinosaurus’s updated look:

This trackway from a swimming animal may have been made by a Spinosaurus (photo by Loic Costeur):

A male Danube crested newt, with a tail that somewhat resembles that of Spinosaurus:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

If you follow any paleontologists on social media, you’ve probably heard them talking about the new spinosaurus article just published in Nature. It sounds like the sort of discovery that makes other paleontologists take a closer look at fossils of dinosaurs related to spinosaurus, so this week let’s find out what the discovery is and what it means!

I could swear we’ve talked about Spinosaurus before, but a quick search revealed that we actually learned about its relative, Baryonyx, in episode 151. Baryonyx grew at least 33 feet long, or 10 meters, and lived around 125 million years ago. It had a skull similar to Spinosaurus’s but otherwise didn’t resemble it that much, and as far as we know it waded in shallow water to catch fish and other aquatic animals.

Spinosaurus was a therapod dinosaur that lived in the Cretaceous, roughly 112 to 93 million years ago. It lived in what is now North Africa and the species we’re talking about today is Spinosaurus aegyptiacus, which as you can probably guess was first discovered in Egypt.

Spinosaurus was as big as Tyrannosaurus rex, possibly larger depending on what measurements you’re looking at. It could probably grow some 52 feet long, or 16 meters, possibly as much as 59 feet long, or 18 meters. But it didn’t look very much like a T. rex. For one thing, its front legs were large and strong. Instead of T. rex’s massive skull and jaws, Spinosaurus had a more slender, narrow skull that was shaped something like a crocodile’s. It also had long neural spines on its back that may have formed a type of sail similar to Dimetrodon’s, although of course Spinosaurus and Dimetrodon weren’t related at all. Dimetrodon wasn’t a dinosaur or even technically a reptile, as we learned in episode 119.

Spinosaurus’s neural spines could grow almost five and a half feet long, or 1.65 meters, and if they did form a sail, it was roughly squared off instead of shaped like a half-circle. Some researchers think it wasn’t a sail at all but a fatty hump on its back something like a buffalo’s shoulder hump or a camel’s humps. The neural spines would help give the hump structure. Other researchers think it was a sail used for display, while one team of paleontologists suggested as early as 2014 that it was a sail that acted as a dorsal fin in the water, since it’s shaped like a sailfish’s dorsal fin.

Spinosaurus probably ate both meat and fish, so it makes sense that it lived in swampy areas like mangrove forests and tidal flats where it could hunt both terrestrial and water animals. Its hind legs were short, its feet were flat with long toes, and its toes may have been webbed. Its hind feet actually share features found in modern shorebirds, which suggests it spent a lot of time walking on soft ground like sand, marsh, and shallow water.

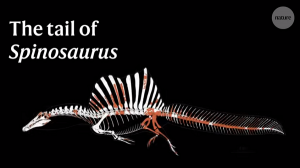

Despite its body length and short legs, Spinosaurus walked on its hind legs. Its tail was very long to balance the front of its body. And it’s the tail that is the focus of the Nature article everyone’s talking about right now.

See, despite Spinosaurus’s fish-eating, almost no one thought it was an aquatic dinosaur. No one thought any dinosaur swam around routinely to catch fish. The big predators that lived in oceans and fresh water at the same time as the dinosaurs were not dinosaurs, but were reptiles like the crocodile and Mosasaurus.

A few paleontologists, like the team that suggested Spinosaurus’s neural spines formed a sort of dorsal fin, had started suggesting Spinosaurus and its close relations were semi-aquatic. But almost no one agreed. Most scientists pointed out that Spinosaurus looked like an ordinary wading animal, not a swimming animal.

Then, in an article published in Nature on April 29, 2020, a new study revealed that Spinosaurus’s tail isn’t the ordinary long, skinny dinosaur tail. Instead, new physical models of its tail show “unambiguous evidence of [the tail acting as] an aquatic propulsive structure”. In other words, Spinosaurus could not only swim, it could probably swim quite well.

Its tail had tall neural spines like the ones on its back, some of them two feet long, or 61 cm, which gave it more surface area to push against the water. It was flexible and strong too.

So how come no one had noticed this before? Well, no one had the right fossils. Most of the tail bones studied were only found in 2018 and 2019 in Morocco by a team of Italian paleontologists. And guess what! The team of paleontologists were the same ones who suggested a few years ago that the neural spines on Spinosaurus’s back acted as a dorsal fin, led by a man named Nizar Ibrahim. While we still don’t know for sure, it’s looking more and more like they were correct. A dorsal fin provides stability in the water, and of course it could also act as a display feature to attract mates.

We don’t have very many Spinosaurus fossils. The only good specimen ever found was destroyed by a bomb in World War II, and it didn’t have a tail anyway. Until the 2018 expedition started turning up Spinosaurus vertebrae, no one knew what the tail looked like at all. The expedition found most of its tail and a lot of the rest of its bones, including part of the skull. While the fossils were found in the Sahara, back when Spinosaurus was alive the area was swampy and full of rivers, home to lots of large animals, including coelacanths and crocodiles. But Spinosaurus was probably the largest.

There is an animal that has a similar body plan to Spinosaurus’s, an amphibian called the Danube crested newt. It lives in parts of central Europe. It grows to about 7 inches long, or 18 cm, although males are smaller. It’s dark brown with black and white spots and an orange belly with larger black spots. During breeding season, the male develops a crest on its back and tail that does look a little bit like Spinosaurus’s sails. During the fall and winter it lives in the forest, but the rest of the year it lives in water. It eats small animals like insects and tadpoles.

The paleontologists studying Spinosaurus’s tail made a model of the Danube crested newt’s tail and some other animal tails and tested them to see which tail worked best to provide thrust underwater. The newt’s tail won.

That doesn’t mean Spinosaurus was necessarily a fast swimmer. The tail alone would allow it to move forward at around five miles an hour, or 1.6 km per hour. You can walk faster than that with a little effort. But if Spinosaurus also had webbed feet, it could have used them for extra propulsion in the water. It may have cruised through the water at a leisurely pace and ambushed unwary fish and other animals. In shallow water it could have used its hind feet to push off the bottom while it remained buoyant, and in fact we even have fossilized underwater tracks that may be made by Spinosaurus.

Other Spinosaurids were probably at least semi-aquatic too, although they don’t seem to be as well adapted to the water as Spinosaurus was. But now that they know what to look for, it could be that paleontologists will discover more evidence of aquatic dinosaurs soon.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast online at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. If you like the podcast and want to help us out, leave a rating and review on Apple Podcasts or wherever you listen to podcasts. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us that way.

Thanks for listening!