Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 11:41 — 13.5MB)

Sign up for our mailing list! We also have t-shirts and mugs with our logo!

A big birthday shout-out to Penelope this week! Thanks to Isaac for this week’s topic suggestion. We’re learning all about the sable and sable antelope!

Further reading (mostly for the pictures since there’s not much content otherwise):

Woman Rescues This Sable from Becoming Someone’s Coat

Further watching:

Kruger Park, Season 15 – this one is about some sable antelope bulls fighting

Fuzzy sable face:

Sable:

Sable antelopes:

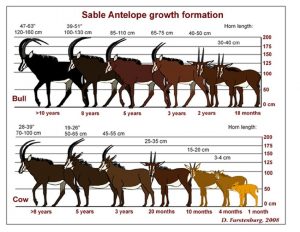

A sable antelope growth chart. I find this really interesting. NERD:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

This week we’ve got an interesting theme, with both the theme and the animals suggested by Isaac. But first, we have a birthday shout-out!

Happy birthday this week to Penelope, whose birthday is on January 15th! I hope you have the best birthday ever!

Isaac suggested the sable, which is a type of mustelid, or weasel and ferret relation, and also suggested the sable antelope! It’s the sable episode.

The word sable means black or a rich dark brown, but most of the time it’s used to refer to the fur of an animal called the sable. The fur was so highly prized in Europe and Asia that the color of the animal’s fur was used as the name of the animal itself, and has been borrowed to refer to a specific coloration of other animals like cats and dogs.

The animal called the sable is common throughout parts of Asia, especially Siberia, China, and northern Mongolia. It lives in forests and mostly hunts by sound, and will eat just about anything it can find. This includes small animals like hares, rodents, birds, and even other species of mustelid, but it will also eat carrion, berries, fish, insects, snails and slugs, and occasionally it will even manage to kill a small bovid called a musk deer. The musk deer isn’t actually a deer but is more closely related to goats and antelopes. It can stand over two feet tall at the shoulder, or 70 cm, and the male has fang-like tusks instead of antlers or horns.

For an animal that sometimes kills and eats musk deer, the sable isn’t very big. It’s long and slender like other mustelids and measures nearly 2 feet long, or 56 cm, not counting its tail, which can add another 5 inches, or 12 cm. Females are a little smaller. It’s brown all over, usually dark brown but sometimes lighter depending on where it lives, with a pale patch on its throat. It has large fox-like ears and a somewhat fox-like or cat-like face but with smaller eyes. Its legs are short but that doesn’t stop it from covering long distances every day to find enough food, more than seven miles in some cases, or 12 km.

The sable is crepuscular, meaning it’s most active during dawn and dusk. When it’s not out hunting, it sleeps in a burrow it digs among tree roots, often lined with leaves and dry grass so it’s more comfortable and warmer. The exception is during mating season when the sable is more likely to be out during the daytime. Males fight each other during this time, and when a female is deciding whether she likes a male, she and the male will play-fight and chase each other.

One unusual thing about the sable is that even though mating season is usually in summertime, and even though it only takes about a month for the babies to develop inside the mother before they’re born, the babies are born in spring. Since the sable doesn’t have access to a time machine, something else is going on.

It’s called delayed implantation or embryonic diapause, where the mother’s egg is fertilized but then stays dormant for a time before it attaches to the uterine wall and starts developing into an embryo and ultimately a baby ready to be born. This allows babies to be born at a time of year when there’s plenty of food. In the sable’s case, the fertilized eggs don’t implant for 8 months.

Sables aren’t the only mammals that practice delayed implantation. A lot of mustelids do, as well as bears, seals, armadillos, and many others. A slightly different variety of delayed implantation only happens when the mother already has a baby that’s nursing, meaning she’s still producing milk. That’s hard on the body, so in some mammals, including some rodents and marsupials, the fertilized egg waits to implant until the mother is no longer producing milk. That way the mother has more resources available to nourish the growing embryo instead of having to divide her energy between her developing embryos and her already-born babies. In other mammals, including humans, a nursing mother doesn’t usually produce eggs to be fertilized until she’s stopped producing milk for her baby.

A female sable usually has two or three babies in a litter but sometimes more. The babies are born with a little bit of fuzzy hair to help keep them warm, but like puppies and kittens they’re born with their eyes sealed shut. It takes about a month for their eyes to open. The mother weans them when they’re about two months old but continues to take care of them, first by regurgitating food for them to eat, then by teaching them how to hunt and forage for themselves.

The sable’s fur is exceptionally soft and beautiful, and as a result it’s been killed for its fur for centuries and has always been expensive to buy. One Russian population is jet black with a white tip to each hair, which was even more highly prized than the rest. But the best way to experience the beautiful fur of a sable is by petting a live one, not the skin of a dead one. Some people have started keeping sables as pets, although they’re not actually domesticated and can be difficult or even dangerous to keep.

Next, another beautiful non-domesticated animal is the sable antelope. It lives in forested savannas in parts of eastern and southern Africa. There are four subspecies, the largest of which is the giant sable antelope. That makes it sound enormous but it’s only a little bigger than other subspecies, and is critically endangered. In fact, the giant sable antelope was suspected of having gone extinct during a terrible civil war in Angola, which is the only place in Africa where it lives. Fortunately a herd of them was caught on camera trap in 2004, and the giant sable antelope is now protected.

Sable antelope cows give birth to one baby during the rainy season, which varies depending on where they live. The calves are light brown or pale reddish-brown but as they grow older, their fur becomes darker. Mature females are usually dark brown but adult males are black. Adults and older calves also have white patches on the face, belly, and rump.

The sable antelope has a short tail with a little tuft at the end, and it also has a short mane that usually stands upright like a donkey’s mane. Males are bigger than females, standing some 4 and a half feet tall at the shoulder, or 1.4 meters.

Both males and females have horns, though. Antelopes are bovids, which means they have true horns like cattle and goats, not antlers like deer that are shed every year. The sable antelope’s horns are really impressive, too. They’re dark gray or black and arch up and back from the head like really big goat horns. A female can have horns up to 3 and a half feet long, or 102 cm, while a male can have horns 0ver 5 feet long, or 165 cm. That’s right, his horns can be longer than he is tall. Sable antelopes are so spectacular that when you think of an antelope, you probably think of an animal that has horns like this.

Unfortunately, those horns have caused the sable antelope to be a target for big game hunters who want the horns as a trophy. These days, though, the biggest threat is habitat loss as humans fence their grasslands to graze livestock.

During the rainy season, the sable antelope lives in small herds of up to 30 females and their young, who share a territory with a single bull. The herd is led by the oldest females who know where the best places are to graze and find water. When the herd moves, the male usually follows right behind to make sure everyone stays together.

The sable antelope eats tree leaves and some kinds of grass, and spends the hottest parts of the day lying down and chewing its cud because, like other bovids, it’s a ruminant. The calves are always in the middle of the resting herd and the adults lie facing outward so they can watch for danger and meet it with their horns. When the adults are moving around to graze, young calves stay in a group called a creche, watched over by a few adults.

During the dry season when there’s not as much to eat, herds will come together to graze in the best pastures with access to water. When young males mature, the older male drives them away from the herd to fend for themselves. Young bulls often form small bachelor herds or may be solitary.

When a bull challenges another bull in an attempt to take control of his territory, they fight with their horns, although they don’t usually injure each other. The sable antelope also uses its horns to fight off and sometimes even kill predators like lions and leopards.

This is the only reliable audio I could find of a sable antelope. There’s a link to the original video in the show notes. The sound is of a bull who’s stuck in the mud, although he later manages to get out.

[sable antelope sound]

You can find Strange Animals Podcast at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. If you like the podcast and want to help us out, leave us a rating and review on Apple Podcasts or Podchaser, or just tell a friend. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us for as little as one dollar a month and get monthly bonus episodes.

Thanks for listening!