Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 11:25 — 12.8MB)

Thanks to Maryjane and Siya for their suggestions this week!

Further reading:

Look, don’t touch: birds with dart frog poison in their feathers found in New Guinea

The hooded pitohui:

The rufous-naped bellbird:

The regent whistler:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

This week we’re going to learn about some birds that by human standards seem pretty mean, although of course the birds are just being birds. Thanks to Maryjane and Siya for their suggestions this week!

We’ll start with Maryjane’s suggestion, the Northern shrike. It lives in North America, spending winter in parts of Canada and the northern United States. In summer it migrates to northern Canada. It’s a lovely gray and black bird with a dark eye streak, white markings on its tail and wings that flash when it flies, and a hooked bill. It’s a strong bird about the size of an American robin, and both the male and female sing. They will sometimes imitate other bird songs, and during breeding season a pair will sing duets. The Northern shrike looks very similar to the loggerhead shrike that lives farther south, in the southern parts of Canada and throughout most of the United States and Mexico.

Most important to us today, the Northern shrike is sometimes called the butcher bird, because in the olden days, butchers would hang meat up to cure–but we’ll get to that part.

It prefers to live in the edges of a forest near open spaces, and in the summer it lives along the border of the boreal forest and tundra. While it’s just a little songbird, in its heart it’s a falcon or hawk. It eats a lot of insects and other invertebrates, especially in summer, but it mainly kills and eats other songbirds and small mammals like mice and lemmings, even ones that are bigger and heavier than it is.

The shrike has ordinary feet for a perching bird, not talons, but its feet are strong and can hold onto struggling prey. Its beak is deadly to small animals. The bill has a sharp hook at the end and is notched so that it has two little projections that act like fangs. It will hover and drop onto its prey, or grab a bird in mid-flight and bear it to the ground to kill it. Sometimes it will hop along the ground until it startles a bird or insect into flying away. It will even flash the white patches on its wings to frighten hidden prey into moving.

If the shrike kills a wasp or bee, it will remove the stinger before eating it. It will pick off the wings of large insects and will sometime beat a dead insect against a rock or branch to soften it up and break off parts of the hard exoskeleton before eating it.

Shrikes are territorial and will chase away birds that are much bigger than them, like ducks and even geese. During nesting season, the female takes care of the eggs and the male provides food for her. To prove that he can provide lots of food for the female while she’s incubating the eggs, he will cache food throughout his territory in advance. This is something shrikes do anyway, but it’s especially important during nesting season.

If a shrike catches an animal it doesn’t want to eat right away, it will store it for later. It will cram it into a crack in a rock, impale it on a thorn or other sharp item like the points of a barbed wire fence, or wedge it into the fork of a tree branch. Then it can come back and eat it in a day or two when it’s hungry, or take the food to its mate.

When the eggs hatch, both parents help feed the babies. When the babies are old enough to leave the nest, the parents go their separate ways, but they will often each take some of the fledglings with them so they can continue to feed them and help them learn to hunt. Since a nest can have as many as nine babies, it’s not always possible for one parent to take all the babies. The siblings stick together even once they’re mostly grown and independent, often through their first winter.

This is what a Northern shrike sounds like:

[Northern shrike call]

We talked about some poisonous birds in episode 222, but Siya wanted to learn more about them. In that episode we mostly talked about the hooded pitohui, but since then, two more poisonous birds have been discovered in New Guinea.

Let’s refresh our memories about the hooded pitohui, mostly because its discovery by scientists is such a fun story.

The hooded pitohui lives in forests throughout much of New Guinea and eats seeds, insects and other invertebrates, and fruit. It’s related to orioles and looks very similar, with a dark orange body and black wings, head, and tail. It’s a social songbird that lives in family groups where everyone works to help raise the babies.

The people who live in New Guinea knew all about its toxicity, of course. They mentioned this to European naturalists as long ago as 1895, but weren’t believed, because the scientists had never heard of a toxic bird. It wasn’t until 1989 that a grad student studying birds of paradise made a surprising discovery.

Jack Dumbacher was trying to net some birds of paradise to study but kept catching pitohuis in his nets. He would untangle the birds and let them fly away, but naturally they were upset and one scratched him. He was in a hurry so he just licked the cuts clean. His tongue started to tingle, then burn, and then it went numb.

Fortunately the effects didn’t last long, but he mentioned it to another researcher who had had a similar experience. They realized something weird was going on, so Dumbacher asked some of the local people what the cause might be. They all said, “Yeah, don’t lick the pitohui bird.”

Dumbacher did, though, because sometimes scientists have to lick things. The next time his nets caught a pitohui, Dumbacher plucked one of its feathers and put it in his mouth. His mouth immediately started to burn.

Dumbacher was amazed to learn about a toxic bird, but it took a year for anyone else to take an interest, specifically Dr. John W. Daly, an expert in poison dart frogs in Central and South America. Back in the 1960s while he was studying the frogs, in order to determine which ones were actually toxic and which ones weren’t, he frequently poked a frog and licked his finger, so Daly completely understood Dumbacher putting a feather in his mouth.

Maybe don’t put random stuff in your mouth. Both Dumbacher and Daly were lucky they didn’t die, because it turns out that poison dart frogs and pitohuis both contain one of the deadliest neurotoxins in the world, called batrachotoxin.

A chemical analysis determined that both animals excrete the same toxin. In captivity, poison dart frogs lose their toxicity. Daly was the one who figured this out, but he couldn’t figure out why except that he was pretty sure they absorbed the toxins from something they were eating in the wild. He thought the same might be true for the pitohui.

Dumbacher agreed, and after he achieved his doctorate he started making expeditions to New Guinea to try to find out what. Both he and Daly thought it was probably an insect. But there are a lot of insects in Papua New Guinea and he couldn’t stay there and test insects for toxins all the time. He came and went as often as he could, and to make his trips easier he left his equipment in a village rather than hauling it back and forth with him.

What he didn’t know is that one villager, named Avit Wako, had gotten interested in the project. When Dumbacher was gone, he continued the experiments. In 1995 Dumbacher sent a student intern to the village, since he didn’t have time to go himself, and Avit Wako said, “Hey, good to see you! I solved your problem. The toxin comes from this particular kind of beetle.” He was right, too. The toxin comes from beetles in the genus Choresine.

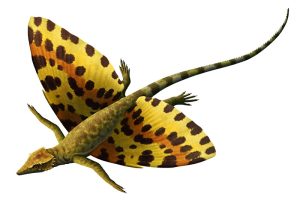

But the pitohui isn’t the only toxic bird in New Guinea. In 2018 and 2019, two researchers from the University of Copenhagen in Denmark got interested in poisonous birds and did some studies. One of the scientists is Kasun Bodawatta, whose colleagues thought he was having a rough time during the trip. The life of a scientist in the field can be hard, and Bodawatta kept having issues with a runny nose and weepy eyes. It wasn’t allergies or exhaustion, though, but the result of handling poisonous birds and their feathers. He described it as feeling “like cutting onions, but with a nerve agent.”

Bodawatta’s team discovered that two more birds in New Guinea contain the same toxins as the pitohui in their feathers and skin. The rufous-naped bellbird is gray-brown with white and yellow markings, and a patch of rufous on the back of its head. The regent whistler is black and yellow with a white patch on its throat. Both eat insects as a large part of their diets, and both show similar genetic mutations that allow them to sequester the Choresine toxins in their feathers and skin. Not only does this keep potential predators from eating the birds, it also probably helps kill mites and other parasites that might otherwise want to live in their feathers.

A 2023 study on the birds’ toxins discovered something new. In addition to the neurotoxin the birds absorb from beetles, the regent whistler’s skin also contains a different toxin that doesn’t have anything to do with beetles or other insects. The regent whistler’s skin glands contain a population of symbiotic bacteria that secrete a completely different toxin made of previously unknown molecules. The toxin helps protect the birds from harmful bacteria and fungi that are known to infect the skin and feathers of birds.

In 2024, a team of microbiologists and chemists began studying the antimicrobial secretions in hopes of creating a new type of antimicrobial drug for use in humans and other animals. So thank you, little birds, and thank you to the scientists and citizen scientists who study them.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us for as little as one dollar a month and get monthly bonus episodes.

Thanks for listening!