Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 10:48 — 12.2MB)

This week we have a mystery animal from South America, the hueque!

Further reading:

Llamas are having a moment in the U.S., but they’ve been icons in South America for millennia

Whatever happened to the hueque? Seeking the lost llama of Chile

A dressed up person and her dressed up llama (picture from llama article linked above):

The noble guanaco:

Cuddly alpacas!

The noble vicuña:

A 1646 picture of a hueque:

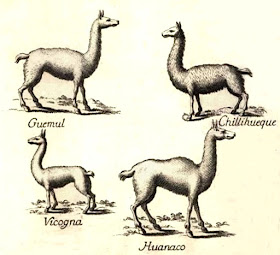

A 1776 engraving of four camelids of South America, including the hueque. The “guemul” in the upper left is actually a llama (the huemul is a type of deer found in a small part of southern Patagonia):

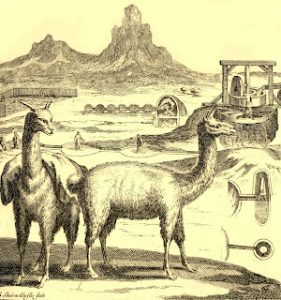

A 1716 engraving supposedly depicting a hueque (central figure) alongside a llama (on the left with the carry-bags over its back):

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

We’ve done a lot of listener suggestions lately and I still have lots more, but this week let’s look at a mystery animal that I really want to learn more about. It’s a South American animal, specifically from central Chile, called the chilihueque or hueque.

Whether the heuque turns out to be an animal unknown to science or not, it’s definitely a camelid of some kind. Camelids include camels, llamas, and their relations, four of which are native to South America. Those four are the guanaco, the llama, the vicuña, and the alpaca, which are all closely related.

The vicuña lives in high elevations in the Andes Mountains while the guanaco lives in lower elevations. The vicuña is smaller and more delicate than the guanaco. It grows not quite three feet tall at the shoulder, or about 85 cm, with a long, slender neck and small head, and a short fuzzy tail. Its legs are long and slender too. It’s white and light brown with thick, incredibly soft fur that keeps it warm in its mountain home. It eats grass and other plants.

The vicuña lives in small groups, usually consisting of a male, several females, and their babies. When the babies are about a year old or a little older, males leave and initially form small bachelor groups while females leave and form small groups too, called sororities. Eventually both males and females of various bachelor groups and sororities will seek each other out during mating season.

Vicuña wool is extremely soft and fine, and in the days of the Inca Empire, around 500 to 600 years ago, only royalty were allowed to wear clothes made of it. It’s actually not wool like sheep wool but a fiber similar to cashmere from goats or angora from bunnies. Because the vicuña is a wild animal, it has to be captured and its fur cut off, or shorn, but it’s hard to catch. Not only that, since the vicuña is small, it doesn’t give very much fiber so you need to shear a whole lot of the animals to get enough to make a single piece of clothing.

In the olden days, the Inca people constructed traps and worked together to herd vicuña into the traps. Then they would shear the animals and release them again, but only once every four years. These days the practice has been re-instituted by the Peruvian government, although the capture and shearing is done every three years. The fiber is only supposed to be sold outside of Peru after it has been certified by the government as being gathered lawfully and humanely, and most of the money remains with the villagers who gather it. It’s extremely expensive to buy, but unfortunately that means that poachers will sometimes kill the animals to shear and sell the fiber illegally, even though it’s a protected species.

I don’t remember if I’ve ever mentioned this on the podcast, but one of my hobbies is spinning. I can take raw wool from a sheep or fiber from some other animal and turn it into yarn or thread using my spinning wheel or hand spindle, and yes, I have bought legal vicuña fiber and spun it into thread. I bought a single gram of it ages ago, and spun it using a very small support spindle, because the fibers are so fine and short that they’re hard to spin any other way. My single gram produced enough thread to knit into a square about the size of a small handkerchief, which I made for a quilt the handspinning guild I was part of at the time was putting together to showcase all sorts of different animal fibers. It was a pretty amazing quilt, by the way. One woman cut her own hair short and spun her hair into thread which she then wove into a square with a small hand loom. Human hair is actually really coarse when you spin it, because the ends stick out and are prickly.

Anyway, the guanaco is very similar to the vicuña but it’s a larger, more robust animal that’s brown above and white underneath, with a gray face. It’s common in the lower elevations of the Andes and throughout much of Patagonia. It also produces soft fiber, but it’s not quite as fine or soft as the vicuña’s.

The alpaca is the domestic descendant of the vicuña while the llama is the domestic descendant of the guanaco. One interesting thing is that all four of these animals have quite thick skin on the neck. This helps protect their necks from the bites of predators.

All these animals are in the genus Lama, and they all look very similar, like small, delicate camels without humps. But until just a few hundred years ago, there might have been a fifth member of the genus Lama in parts of Chile, the hueque.

As reported by Spanish and Dutch explorers and colonizers, the hueque was a domesticated animal kept for its meat and its fine, soft, very long fur. Its fur was so long that it supposedly brushed the ground. It wasn’t supposed to be the same animal as the guanaco, which lived in the area and was also sometimes kept as a semi-domesticated animal. It was smaller than a llama or guanaco but larger than a vicuña, standing up to four feet tall at the shoulder, or about 1.2 meters.

As more Spanish colonized Chile and other parts of South America, bringing sheep and cattle with them, the hueque became less and less common. Not only did the introduced animals compete with the hueque and other South American camelids for resources, they brought diseases that camelids could catch. Eventually the local people switched to raising sheep for wool and meat and the hueque was supposed to have died out completely by the late 18th century.

Many people have suggested that the hueque was actually another word for the alpaca, which did decline in numbers during this time, although of course it didn’t go extinct. The hueque might have been a particular variety of alpaca or even a subspecies that looked somewhat different. Remember that the alpaca is a domesticated animal descended from the vicuña. Other people hypothesize that the hueque was a type of llama or guanaco, and remember that the llama is the domesticated descendant of the guanaco.

In December of 2016, the scientific journal Nature published a genetic study of camelid remains found on Isla Mocha, a volcanic island off the coast of Chile. The people living on the island in the early 17th century kept hueques, according to reports of Dutch and Spanish explorers. People have lived on the island for about 1,500 years but the hueque probably didn’t. Instead, it was transported to the island in small boats on special occasions, to be used as ritual sacrifices where the meat was then eaten. Then again, there is at least one report that the animal did live on the island and was used to pull plows or possibly wagons.

A 1615 report by a Dutch captain who saw the hueque is that it was like a “sheep of a very wonderful shape, having a very long neck and a hump like a camel, a hare lip and very long legs.” This is strange because while it is otherwise a good description of any South American camelid, no South American camelid has a hump like a camel. The hump the captain reported might actually have been thick fur that can look a little bit like a hump above the shoulders.

The 2016 report looked at DNA samples extracted from the subfossil remains of 14 camelids found on the island, including the complete genomes of three individual animals. Then the samples were compared to those of other South American camelids. They most closely matched the DNA profile of the guanaco.

The study suggests that “chilihueque” was the local term for the guanaco, especially a guanaco kept as a domesticated or semi-domesticated animal.

That’s just one study of one specific island, of course. Hopefully genetic analysis of other camelid remains will be made soon and we can learn more about what exactly the hueque might have been.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. If you like the podcast and want to help us out, leave us a rating and review on Apple Podcasts or Podchaser, or just tell a friend. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us for as little as one dollar a month and get monthly bonus episodes.

Thanks for listening!