Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 7:51 — 8.7MB)

Further reading:

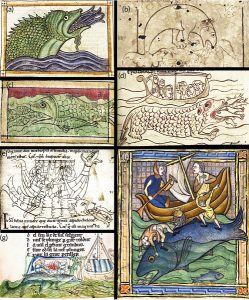

Many renditions of the hafgufa/aspidochelone:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

Back in the olden days, as much as 1700 years ago and probably more, up through the 14th century or so, various manuscripts about the natural world talked about a sea monster most people today have never heard of. In ancient Greek it was called aspidochelone, contracted to aspido in some translations, while in Old Norse it was called the hafgufa. But it seemed to be the same type of monster no matter who was writing about it.

The animal was a fish, but it was enormous, big enough that it was sometimes mistaken for an island. When its jaws were open they were said to be as wide as the entrance to a fjord. A fjord is an inlet from the sea originally formed by glaciers scraping away at rocks, and then when the glaciers melted the sea filled the bottom of what was then a steep valley. I’m pretty sure the old stories were exaggerating about the sea monster’s mouth size.

The sea monster ate little fish, but it caught them in a strange way. It would open its mouth very wide at the surface of the water and exude a smell that attracted fish, or in one account it would regurgitate a little food to attract the fish. Once there were lots of little fish within its huge mouth, it would close it jaws quickly and swallow them all.

Generally, any sea monster that’s said to be mistaken for an island was inspired by whales, or sometimes by sea turtles. The hafgufa is actually included in an Old Norse poem that lists types of whales, and the aspidochelone was considered to be a type of whale even though the second part of its name refers to a sea turtle. So whatever this sea monster was, we can safely agree that it wasn’t a fish, it was a whale. Up until just a few centuries ago people thought whales were fish because of their shape, but we know now that they’re mammals adapted to marine life.

But the hafgufa’s behavior is really weird and doesn’t seem like something a whale would do. We’ve talked about skim feeding before, where a baleen whale cruises along at the surface with its mouth held open, until it’s gathered enough food in its mouth and can swallow it all at once. But whales aren’t known to hold their mouths open at the surface of the water and just sit there while fish swim in. At least, they weren’t known to do this until 2011.

In 2011, marine biologists studying humpback whales off Canada’s Vancouver Island in North America observed some of the whales catching herring and other small fish in an unusual way. The whales would remain stationary in the water, tails straight down with the head sticking up partly out of the water. A whale opened its mouth very wide and didn’t move until there were a lot of fish in its mouth, which it then swallowed. Soon after, another team of marine biologists studying Bryde’s whales in the Gulf of Thailand in South Asia observed the same activity when the whales were feeding on anchovies at the surface of the water.

The term for this activity is called trap feeding or tread-water feeding, and at first the scientists thought it was a response to polluted water that had caused the fish to stay closer to the surface. But once the two teams of scientists compared notes, they realized that it didn’t appear to have anything to do with pollution. Instead, it’s probably a way to gather food in a low-energy way, especially when there isn’t a big concentration of fish in any particular spot, and when researchers remembered the story of the hafgufa, they realized they’d found the solution to that mystery sea monster.

The only question was whether the accounts were accurate that the hafgufa emitted a smell or regurgitated food to attract fish. Further observation answered that question too, and it turns out that yes, the old stories were at least partially right. The smell has been compared to rotten cabbage, but it isn’t emitted by the whale on purpose. It’s a smell released when phytoplankton is eaten in large numbers, whether by fish or whales or something else, and it does attract other animals.

As for the regurgitation, this is always something that happens to some degree when a baleen whale feeds. The whale fills its mouth with water that contains the fish and other small animals it eats, and it presses its huge tongue upwards to force the water through its baleen, which acts as a sieve. Whatever’s left in its mouth after the water is expelled, it swallows. But baleen is tough and fish are small and delicate in comparison. Often, fish and other small animals get squished to death against the baleen, and parts of them are expelled with the water. This creates a sort of yucky slurry that could be interpreted as a whale regurgitating food to attract more fish. The scientists think that fish are mainly attracted not to any smell or potential food in the water, but to the supposed shelter offered by the whale’s giant mouth.

It appears that trap feeding is a fairly rare behavior in whales, but one that’s been around a lot longer than the last few years. It’s also possible that because whaling drove many species nearly to extinction and whale numbers are only just starting to recover, until recently whales didn’t need to use this feeding strategy. It seems to be used when a preferred food is widely scattered so that chasing after the fish isn’t worth the energy cost, and that’s more likely to happen when there are a lot of whales around.

It’s amazing that this type of feeding strategy has been identified in two different species of whale, and it’s even more amazing that it matches up so well with ancient accounts. It’s easy to assume that in the olden days, people were kind of stupid, but people back then were just as intelligent as people now. They just didn’t have our technology and modern knowledge. They were often extremely observant, though, and luckily for us, sometimes they were able to write their observations down in books that we can still read.

Thanks for your support, and thanks for listening!