Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 12:43 — 13.9MB)

Thanks to Elizabeth, Alexandra, Kimberly, Ezra, Eilee, Leon, and Simon for their suggestions this week!

Further reading:

New population of blue whales discovered in the western Indian Ocean

An Endangered Dolphin Finds an Unlikely Savior–Fisherfolk

The humpback whale:

The gigantic blue whale:

The tiny vaquita:

The Indus river dolphin:

The false killer whale:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

This week we’re going to have a big episode about various dolphins and whales! We’ve had lots of requests for these animals lately, so let’s talk about a bunch of them. Thanks to Elizabeth, Alexandra, Kimberly, Ezra, Eilee, Leon, and Simon for their suggestions.

We’ll start with a quick overview about dolphins, porpoises, and whales, which are called cetaceans. All cetaceans alive today are carnivorous, meaning they eat other animals instead of plants. This includes the big baleen whales that filter feed, even though the animals they eat are tiny. Cetaceans are mammals that are fully aquatic, meaning they spend their entire lives in the water, and they have adaptations to life in the water that are simply astounding.

All cetaceans alive today belong to either the baleen whale group, which filter feed, or the toothed whale group, which includes dolphins and porpoises. The two groups started evolving separately about 34 million years ago and are actually very different. Toothed whales are the ones that echolocate, while baleen whales are the ones that have extremely loud, often beautiful songs that they use to communicate with each other over long distances. It’s possible that baleen whales also use a limited type of echolocation to navigate, but we don’t know for sure. There’s still a lot we don’t know about cetaceans.

Now let’s talk about some specific whales. Ezra wanted to learn more about humpback and blue whales, so we’ll start with those. Both are baleen whales, specifically rorquals. Rorquals are long, slender whales with throat pleats that allow them to expand their mouths when they gulp water in. After the whale fills its mouth with water, it closes its jaws, pushing its enormous tongue up, and forces all that water out through the baleen. Any tiny animals like krill, copepods, small squid, small fish, and so on, get trapped in the baleen. It can then swallow all that food and open its mouth to do it again. The humpback mostly eats tiny crustaceans called krill, and little fish.

The humpback grows up to 56 feet long, or 17 meters, with females being a little larger than males on average. It’s mostly black in color, with mottled white or gray markings underneath and on its flippers. Its flippers are long and narrow, which allows it to make sharp turns.

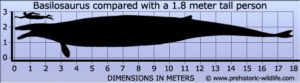

The humpback is closely related to the blue whale, which is the largest animal ever known to have lived. It can grow up to 98 feet long, or 30 meters, and it’s probable that individuals can grow even longer. It can weigh around 200 tons, and by comparison a really big male African elephant can weigh as much as 7 tons. Estimates of the weight of various of the largest sauropod dinosaurs, the largest land animal ever known to have lived, is only about 80 tons. So the blue whale is extremely large.

The blue whale only eats krill and lots of it. To give you an example of how much water it can engulf in its enormous mouth in order to get enough krill to keep its massive body going, this is how the blue whale feeds. When it finds an area with a lot of krill floating around, it swims fast toward the krill and opens its giant mouth extremely wide. When its mouth is completely full, its weight—body and water together—has more than doubled. Its mouth can hold up to 220 tons of water. Since the whale is in the water, it doesn’t feel the weight of the water in its mouth.

Blue whales live throughout the world’s oceans, but a few years ago scientists analyzing recordings of whale song from the western Indian Ocean noticed a song they didn’t recognize. It was definitely a blue whale song, but one that had never been documented before. Not long after, one of the same scientists was helping analyze humpback whale recordings off the coast of Oman and recognized the same unusual blue whale song.

After the finding was announced, other scientists checked their recordings from the Indian Ocean and a few realized they had the mystery blue whale song too. The recordings come from a population of blue whales that hadn’t been documented before, and which may belong to a new subspecies of blue whale.

Elizabeth, Alexandra, and Leon all wanted to learn about dolphins. Kimberly also specifically wanted to learn about the Indus River dolphin and Leon about the vaquita porpoise. Dolphins and porpoises are considered toothed whales, but they’re also relatively small and can swim very fast. Orcas are actually dolphins even though they’re often called killer whales.

Even a small cetacean is really big, but the exception is the vaquita. It’s the smallest cetacean alive today, not even five feet long, or 1.5 meters. It lives only in the upper Gulf of California and is gray above and white underneath, with black patches on its face.

The vaquita spends very little time at the surface of the water, so it’s hard to spot and not a lot is known about it. It mostly lives in shallow water and it especially likes lagoons with murky water, since that’s where it can find lots of the small animals it eats, including small fish, squid, and crustaceans.

The vaquita is critically endangered, mostly because it often gets trapped in illegal gillnets and drowns. There may be as few as ten individuals left alive. Attempts at keeping the vaquita in captivity have failed, but it’s strictly protected by both the United States and Mexico. Some scientists worry that even though vaquita females are still having healthy calves, there are so few of the animals left that they might not recover and are functionally extinct. But only time will tell, so the best thing everyone can do is what we’re already doing, keeping the vaquita and its habitat as safe as possible.

Another small cetacean is the Indus River dolphin, which grows up to 8 and a half feet long, or 2.6 meters. As you can probably guess from its name, it actually lives in fresh water instead of the ocean, specifically in rivers in Pakistan and India. It’s pinkish-brown in color and has a long rostrum, or beak-like nose, which turns up slightly at the end and is filled with sharp teeth that it uses to catch fish and other small animals. Because the rivers where it lives are murky, the dolphin doesn’t have very good eyesight. It probably can’t see anything except light and dark with its tiny eyes, but it can sense its surroundings just fine with echolocation.

Like most cetaceans, the Indus River dolphin is endangered, but it’s doing a lot better these days than it was just a few decades ago. In the 1970s only about 150 of the little dolphins were left alive, and by 2001 there were a little over 600. Today there are around 2,000. Habitat loss, pollution, and accidental drowning in fishing nets are still ongoing problems, but these days the fishing families that live along the river are helping it whenever they can. The fishers rescue dolphins who get stranded in shallow water and irrigation canals, and the government encourages this by paying the fishers a small amount for their help. Since this part of the country is very poor, a little bit of extra money can mean a big difference for the families, and of course their help means a lot to the dolphins too.

One interesting thing is that the Indus River dolphin often swims on its side. That is, it just tips over sideways and swims around as though that’s the most normal thing in the world. Scientists think this helps it navigate shallow water. And the Indus River dolphin isn’t very closely related to other dolphins and whales.

Quite a while ago now, Simon brought the false killer whale to my attention. In 1846 a British paleontologist published a book about British fossils, and one of the entries was a description of a dolphin. The description was based on a partially fossilized skull discovered three years before and dated to 126,000 years ago. It was referred to as the false killer whale because its skull resembled that of a modern orca. Scientists thought it was the ancestor of the orca and that it was extinct.

Or maybe not, because in 1861, a dead but very recently alive one washed up on the coast of Denmark.

The false killer whale is dark gray and grows up to 20 feet long, or 6 meters. It mostly eats squid and fish, including sharks. It’s not that closely related to the orca and actually looks more like a pilot whale. It will sometimes hang out with dolphins, including occasionally hybridizing with bottlenose dolphins, but then again sometimes it will eat dolphins. Watch out, dolphins.

Finally, Eilee wanted to learn about little-known whales, and that definitely means beaked whales. There are 24 known species of beaked whale, but there may still be species unknown to science. We know very little about most of the known species, because they live in remote parts of the ocean. They prefer deep water and are extremely deep divers, with the Cuvier’s beaked whale recorded as diving as deep as 1.8 miles, or almost 3 km, and staying underwater without a breath for 222 minutes. That’s approximately 220 minutes longer than a human can hold their breath.

Let’s finish with Sato’s beaked whale, which was only described in 2019. It’s black with a chunky body and small flippers and dorsal fin. It also has a short beak. It lives in the north Pacific Ocean and was thought to be a darker population of Baird’s beaked whale, which is gray, but genetic studies and a careful examination of dead beached individuals proved that it was a completely different species. It grows up to 23 feet long, or 7 meters, but since no female specimens have ever been found, we don’t know if the female is larger or smaller than the male.

We basically know nothing about this whale except that it exists, and the fact that it is alive and swimming around in the ocean right now, along with other whales, is an amazing, wonderful thing.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us for as little as one dollar a month and get monthly bonus episodes.

Thanks for listening!