Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 15:02 — 15.0MB)

This week we’re learning about the hammerhead worm and the ichthyosaur, two animals that really could hardly be more different from each other. Thanks to Tania for the hammerhead worm suggestion! They are so beautifully disgusting!

Make sure to check out the podcast Animals to the Max this week (and always), for an interview with yours truly. Listen to me babble semi-coherently about cryptozoology and animals real and maybe not real!

Here are hammerhead worms of various species. Feast your eyes on their majesty!

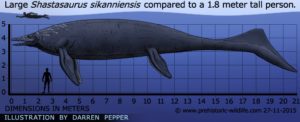

An ichthyosaur:

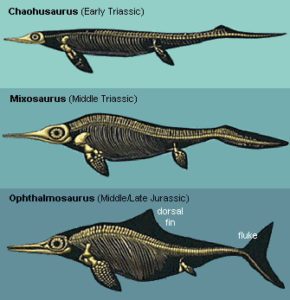

More ichthyosaurs. Just call me DJ Mixosaurus:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

This week we’re looking at a couple of animals that have nothing in common. But first, a big thank you to the podcast Animals to the Max. The host, Corbin Maxey, interviewed me recently and the interview should be released the same day this episode goes live. If you don’t already subscribe to Animals to the Max, naturally I recommend it, and you can download the new episode and listen to me babble about cryptozoology, my favorite cryptids, and what animal I’d choose if I could bring back one extinct species. There’s a link to the podcast in the show notes, although it should be available through whatever app you use for podcast listening.

This week’s first topic is a suggestion from Tania, who suggested hammerheaded animals. We’ve covered hammerhead sharks before way back in episode 15, but Tania also suggested hammerhead worms. I’d never heard of that one before, so I looked it up. I’ve now been staring at pictures of hammerhead worms in utter fascination and horror for the last ten minutes, so let’s learn about them.

There are dozens of hammerhead worm species. They’re a type of planarian, our old friend from the regenerating animals episode, and like those freshwater planarians, many hammerhead worms show regenerative abilities. They’re sometimes called land planarians. Most are about the size of an average earthworm or big slug, with some being skinny like a worm while others are thicker, like a slug, but some species can grow a foot long or more. Unlike earthworms, and sort of like slugs, a hammerhead worm has a flattened belly called a creeping sole. Some hammerhead worms are brown, some are black, some have yellow spots, and some have stripes running the length of their bodies. Hmm, it seems like I’m forgetting a detail in their appearance. …oh yeah. Their hammerheads! Another name for the hammerhead worm is the broadhead planarian, because the head is flattened into a head plate that sticks out like a fan or a hammerhead depending on the species.

The hammerhead worm’s head contains a lot of sensory organs, especially chemical receptors and some eye-like spots that probably can only sense light and dark. Researchers think the worms’ heads are shaped like they are to help the worm triangulate on prey the same way many animals can figure out where another animal is just by listening. That’s why most animals’ ears are relatively far apart, too.

One species of hammerhead worm, Bipalium nobile, can grow over three feet long, or one meter, although it’s as thin as an earthworm. It has a fan-shaped head and is yellowish-brown with darker stripes. It’s found in Japan, although since it wasn’t known there until the late 1970s, researchers think it was introduced from somewhere else. That’s the case for many hammerhead worms, in fact. They’re easily spread in potted plants, and since they can reproduce asexually, all you need is one for a species to spread and become invasive.

While hammerhead worms do sometimes reproduce by mating, with all worms able to both fertilize other worms and also lay eggs, when they reproduce without a mate it works like this. Every couple of weeks a hammerhead worm will stick its tail end to the ground firmly. Then it moves the rest of its body forward. Its body splits at the tail, breaking off a small piece. The piece can move and acts just like a new worm, which it is. It takes about a week to ten days for the new worm to grow a head. Meanwhile, the original worm is just fine and is busy growing another tail piece that will soon split off again into another worm.

One common hammerhead worm accidentally introduced to North America from Asia is frequently called the landchovy. It’s slug-like, tan or yellowish, with a thin brown stripe and a small fan-shaped head. It looks like a leech and if I saw one I would assume that I was about to die. But I would be safe, because hammerhead worms only eat invertebrates, mostly earthworms but also snails, slugs, and some insects.

When a hammerhead worm attacks its prey, say an earthworm, it hangs on to it with secretions that act like a sort of glue. The earthworm can’t get away no matter what it does. The hammerhead worm’s mouth isn’t on its head. It’s about halfway down its body. Once it’s stuck securely to the earthworm, the hammerhead worm secretes powerful enzymes from its mouth that start to digest the earthworm. Which, I should add, is still alive, at least for a little while. The enzymes turn the worm into goo pretty quickly, which the hammerhead worm slurps up. The hammerhead worm’s mouth is also the same orifice that it expels waste from. I’m just going to leave that little factoid right there and walk away.

Hammerhead worms haven’t been studied a whole lot, but some recent studies have found a potent neurotoxin in a couple of species. That could explain why hammerhead worms don’t have very many predators. Or many friends.

[gator sound]

Our next animal is a little bit bigger than the hammerhead worm, but probably didn’t have a hammerhead. We don’t know for sure because we don’t have a complete skeleton, just a partial jawbone. It’s the giant ichthyosaur, and its discovery is new. In May of 2016 a fossil enthusiast named Paul de la Salle came across five pieces of what he suspected was an ichthyosaur bone along the coast of Somerset, England. He sent pictures to a couple of marine reptile experts, who verified that it was indeed part of an ichthyosaur’s lower jawbone, called a surangular. They got together with de la Salle to study the fossil pieces, and after doing size comparisons with the largest known ichthyosaur, determined that this new ichthyosaur probably grew to around 85 feet long, or 26 meters.

So what is an ichthyosaur? Ichthyosaur means fish-lizard, which is a pretty good name because they are reptiles that adapted so well to life in the ocean that they came to resemble modern fish and dolphins. This doesn’t mean they’re related to either—they’re not. But if you’ve heard the phrase convergent evolution, this is a prime example. Convergent evolution describes how totally unrelated animals living in similar habitats often eventually evolve to look similar due to similar environmental pressures.

The first ichthyosaurs appear in the fossil record around 250 million years ago, with the last ones dated to about 90 million years ago. In 1811, a twelve-year-old English girl named Mary Anning took her little brother Joseph to the nearby seashore to look for fossils they could sell to make a little money, and they discovered the first ichthyosaur skeleton. That sounds pretty neat, but Mary’s story is so much more interesting than that. First of all, when Mary Anning was barely more than a year old, a neighbor was holding her and standing under a tree with two other women, when the tree was struck by lightning. The three women all died, but Mary survived. She had been considered a sickly child before that, but after the lightning strike she was healthy and grew up strong.

Mary’s family was poor, so anything she and her brother could do to make money helped. At the time, no one quite understood what fossils were, but people liked them and a nice-looking ammonite or other fossilized shell could bring quite a bit of money when sold as a curio. Mary’s father was a carpenter, but the whole family was involved in collecting fossils from the nearby cliffs at Lyme Regis in Dorset, where they lived, and selling them to tourists. After her father died, selling fossils was the only way the family could make money.

As Mary and her brother became more proficient at finding and preparing fossils, geologists became more and more interested. She made detailed drawings and notes of the fossils she found, and read as many scientific papers as she could get her hands on. At the time, women weren’t considered scholars and certainly not scientists, but Mary taught herself so much about fossils and anatomy that she literally knew more about ichthyosaurs than anyone else in the world.

When Mary was 27 years old, she opened her own shop, called Anning’s Fossil Depot. Fossil collectors and geologists from all over the world visited the shop, including King Frederick Augustus II of Saxony, who bought an ichthyosaur skeleton from her. Collecting fossils could be dangerous, though. In 1833 she almost died in a landslide. Her little dog Trey was just in front of her, and he was killed by the falling rocks. Probably Trey had not heard about the lightning incident or he wouldn’t have stuck so close to Mary.

Although Mary Anning was an expert, and every collection and museum in Europe contained fossil specimens she had found and prepared, she got almost no credit for her work. She was not happy about this, either. Her discoveries were claimed by others, just because they were men. Mary was the one who figured out that the common conical fossils known as bezoar stones were fossilized ichthyosaur poops, called coproliths. Her expertise wasn’t just with ichthyosaurs, either. She was also an expert on fossil sharks and fishes, pterosaurs, and plesiosaurs, and she discovered ink sacs in belemnite fossils. Her friends Anna Pinney and Elizabeth Philpot frequently accompanied Mary on collecting expeditions. I picture them frowning and kicking scientific butt.

Okay, back to ichthyosaurs. Ichthyosaurs were warm-blooded, meaning they could regulate their body temperature internally, without relying on outside sources of heat. They breathed air and gave birth to live babies the way dolphins and their relations do. They had front flippers and rear flippers along with a tail that resembled a shark’s except that the lower lobe was larger than the upper lobe. Some species had a dorsal fin too. They had huge eyes, which researchers think indicated they dived for prey. Many ichthyosaur bones show damage caused by decompression sickness, when an animal surfaces too quickly from a deep dive—called the bends by human scuba divers. Not only were their eyes huge, they were protected by a bony eye ring that would help the eyes retain their shape even under deep-sea pressures.

Ichthyosaurs had long jaws full of teeth, but different species ate different things. Many ate fish and cephalopods like squids, while other specialized in shellfish, and others ate larger animals. We have a good idea of what they ate because we have a lot of high quality fossils, so high quality that we can see the contents of the animals’ stomachs. We also have all those coproliths that paleontologists cut open to see what ichthyosaur poop contained.

Ichthyosaurs lived before plesiosaurs and weren’t related to them. Plesiosaurs are usually depicted with long skinny necks, but more recent reconstructions suggest their necks were actually thick, protected by muscles and fat. Ichthyosaurs appear to have been outcompeted by plesiosaurs once they began to evolve, but ichthyosaurs were already on the decline at that point, although we don’t know why.

Until very recently, the biggest known species of ichthyosaur was Shonisaurus sikanniensis, which grew to almost 70 feet long, or 21 meters. It was discovered by Elizabeth Nicholls, continuing Mary Anning’s legacy of kicking butt and finding ichthyosaurs, and described in 2004. But the new ichthyosaur just discovered was even bigger.

In the mid-19th century, some fragments of fossilized bones were found near the village of Aust in England. They were assumed to be dinosaur bones, but now researchers think they may have been from giant ichthyosaurs, maybe even ones bigger than the one whose jawbone was recently found.

As a comparison, the biggest animal ever known to have lived is the blue whale. It’s alive today. Every time I think about that, it blows my mind. A blue whale can grow almost 100 feet long, or 30 meters. Until very recently, researchers didn’t think any animal had ever approached its size. Even megalodon, the biggest shark known, topped out at about 60 feet, or 18 meters. If the estimated size of the giant ichthyosaur, 85 feet or 26 meters, is correct, it’s possible there were individuals that were bigger than the biggest blue whale, or it’s possible that the jawbone we have of the giant ichthyosaur was actually from an individual that was on the small side of average. Let’s hope we find more fossils soon so we can learn more about it.

Mary Anning would have been out there looking for more of its fossils, I know that.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast online at strangeanimalspodcast.com. We’re on Twitter at strangebeasties and have a facebook page at facebook.com/strangeanimalspodcast. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. If you like the podcast and want to help us out, leave us a rating and review on Apple Podcasts or whatever platform you listen on. We also have a Patreon if you’d like to support us that way.

Thanks for listening!