Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 12:58 — 13.1MB)

Thanks to Pranav for this week’s topic, the orca or killer whale!

Further reading:

https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/2019/07/killer-whales-orcas-eat-great-white-sharks/

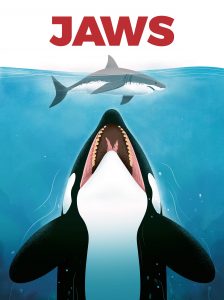

Save Our Seas Magazine (I took the Jaws art below from here too)

An orca:

Orcas got teeth:

Starboard and Port amiright:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

This week let’s return to the sea for a topic suggested by Pranav, the orca. That’s the same animal that’s sometimes called the killer whale. While it is a cetacean, it’s more closely related to dolphins than whales and is actually considered a dolphin although it’s much bigger than other dolphin species.

The orca grows up to 26 feet long, or 8 meters, and is mostly black with bright white patches. The male has a large dorsal fin that can be 6 feet tall, or 1.8 meters, while females have much shorter dorsal fins that tend to curve backwards more than males’ do. Some orcas have lighter coloring, gray instead of black or with gray patches within the black.

The orca lives throughout the world’s oceans although it especially likes cold water. It eats fish, penguins and other birds, sea turtles, seals and sea lions, and pretty much anything else it can catch.

Everything about the orca is designed for strength and predatory skill. It has good vision, hearing, sense of touch, and echolocation abilities. It’s also extremely social, living in pairs or groups and frequently hunting cooperatively.

Some populations of orca live in the same area their whole lives, traveling along the same coastline as they hunt fish. These are called resident orcas and they’re closely studied since researchers can tell individuals apart by their unique markings, so can keep track of what individuals are doing.

Other populations are called transient because they travel much more widely. Transient and resident orcas avoid each other, so they may be separate species or subspecies, although researchers haven’t determined whether this is the case yet. There’s even a newly discovered population of orcas found off the tip of South America that may be a new species. Researchers are analyzing DNA samples taken from the South American orcas with little darts. Fishers had reported seeing odd-looking small orcas in the area for over a decade, but recent photos taken by tourists gave researchers a better idea of what they were looking for. The new orcas have rounder heads and different spotting patterns than other orca populations.

Transient orcas eat more mammals than resident orcas do. Resident orcas mostly eat fish. They have clever ways of catching certain fish, too. A pod of orcas can herd herring and some other fish species by releasing bubbles from their blowholes, which frighten the fish away. A group of orcas releasing bubbles in tandem can make the school of fish form a big ball for protection. Then each orca slaps the ball with its tail. This stuns or even kills some of the fish, which the orca then eats easily. Pretty clever. An orca may also stun larger fish by smacking it with its powerful tail flukes.

But the orca is also good at catching seals and sea lions. Some orcas learn to beach themselves safely when chasing seals, since the seal will often try to escape onto land. Another hunting technique is called wave-hunting, where a group of orcas swim in a way that causes waves to slop over an ice floe. Any animal or bird resting on the ice floe is washed into the water.

Because transient orcas mostly hunt mammals that can hear the orcas’ echolocation clicks and other vocalizations, they tend to stay silent while hunting so they don’t alert their prey. Resident orcas don’t have to worry about noise as much, since most of the fish they eat either can’t hear or their calls or don’t react to them. Resident orcas are much more vocal than transient orcas as a result.

But all orcas have calls they use socially. These are calls that help members of the pod stay in contact, help them coordinate hunting activities, and identify themselves to members of other pods. A pod is usually made up of several family groups, usually ones that are related in some way. You know, like the orca equivalent of an extended family—you and your mom and siblings, maybe your dad, and your mom’s sister and her babies, and so on. Each pod has its own dialect, with their own calls not heard in other pods.

Orcas are also incredibly intelligent and show social traits that match those of humans and chimpanzees, like playfulness, cooperation, and protectiveness. Their social structure is also complex and similar in many ways to those of humans and other great apes. As you may remember from episode 134 about the magpie, complex social structures lead to intelligence in individuals. Individual orcas have what’s known as signature whistles, a unique vocalization that only applies to that one orca. In other words, orcas have names. Researchers have also identified signature whistles in other dolphin species.

Because orcas are so large, so social, so intelligent, and travel such enormous distances every day—up to 50 miles, or 80 km—it doesn’t make any sense to keep them in captivity. But there are a lot of orcas in captivity. In the last decade or so people have started to realize that maybe this is not good for the orcas. Captive orcas develop mental and physical problems that they don’t have in the wild, including bad teeth. A 2017 study of captive orcas found that all of them had tooth problems and more than 65% of them had teeth so worn that the tooth pulp was exposed. That’s the sensitive part of your tooth, so you can imagine the agony this must cause the orca. It’s so bad that over 61% of the orcas studied had had the pulp removed from some of their teeth, which at least stops the pain but which leaves the orca more prone to infection and disease, plus weakens the tooth and can lead to it cracking. Such awful tooth problems mostly result from the orca chewing on concrete and steel in its tank, and this kind of chewing is due to extreme anxiety and other mental problems due to captivity. It’s not seen in orcas in the wild at all. So no, there shouldn’t be any orcas in captivity, or any other cetaceans, unless it’s for rehabilitation purposes with the goal of releasing the orca back into the wild after it’s healthy again.

The orca can live to be at least 90 years old, possibly older. Females especially live much longer than males overall. Female orcas lose the ability to have babies after about age 40 and enter a stage of life called menopause. Humans do this too, and studies show that it’s for the same reasons. Older females help younger females care for their children, and they’re also group leaders who teach younger orcas where to find food and how to catch it.

The orca is an apex predator, meaning there is nothing in the wild that hunts and eats it. Even the great white shark. On average the orca is larger than the great white, and it has an advantage because it hunts cooperatively. Where there are orcas around, there are usually not any great white sharks. This is partly because the two species eat the same thing and the orca out-competes the shark, but it’s also because the orca can and will eat great white sharks.

Some orcas have figured out that they can turn a shark upside down and keep it there in order to hypnotize it. This is called tonic immobility and researchers aren’t entirely sure why it happens, but the shark remains immobile until it wears off after a few minutes. It doesn’t work in all shark species or for every shark, but it makes the shark a lot easier for the orca to kill since it can’t fight back. In 1997 witnesses saw an orca hold a great white upside down for 15 minutes, trying to hypnotize it. It didn’t work, but since sharks have to keep moving to breathe, since they can’t pump water through their gills otherwise, the shark in question actually suffocated and the orca ate it.

But a pair of orcas have taken predation of great white sharks to a whole new level.

The phenomenon was first spotted in 1997 off the coast of San Francisco in western North America. People in a whale-watching tour saw two orcas attack a great white shark and eat its liver. Just its liver. They knew exactly where the liver was and aimed for it during the attack. A great white’s liver is huge and full of yummy fat.

Later that year, researchers studying elephant seals in the area noticed that all the great white sharks that usually preyed on seal colonies had vanished. They’d actually moved out of the area instead of staying to eat the seals. Studies of tagged great whites determined that they avoided orcas to the point of migrating away from feeding sites entirely if orcas were around.

Twenty years later, a marine biologist in South Africa named Alison Kock studied a pair of orcas named Starboard and Port who were attacking sharks the same way and eating their livers. Initially they targeted sevengill sharks, which can grow up to ten feet long, or 3 meters. But all the sevengill sharks fled and in 2017 the carcasses of great white sharks started to wash ashore with their livers eaten. Dr. Kock was pretty sure Starboard and Port were the culprits. When she studied the dead sharks, she recognized tooth marks from orcas.

Remember how earlier I said there were two types of orcas known, the residential and the transient groups? Plus the newly discovered group? Well, there’s actually a fourth group called the offshore orca. These are populations of orcas that live farther away from shore than most other groups. They travel widely and are the only orcas known in the wild to have teeth that are worn down flat almost like the captive orcas. Researchers think the offshore orcas specialize in hunting sharks and their relatives, and that the tooth wear comes from the sharks’ rough skin. Unlike the captive sharks, the tooth wear doesn’t affect the orcas’ overall health. Studies of offshore orcas have determined that more than 93% of their diet is made up of sharks.

Starboard and Port are now mostly after the bronze whaler shark, which grows up to 11 feet long, or 3.3 meters. No shark is safe.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast online at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. We also have a Patreon if you’d like to support us that way.

Thanks for listening!