Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 11:05 — 12.7MB)

This week we answer a question you probably didn’t ask, did dinosaurs ever get sick? The answer is yes (or else it would be a super short episode). (Thanks to Llewelly for some corrections!)

A big birthday shout-out to Gwendolyn! Have a great birthday!

The unlocked Patreon episode about green puppies

Further reading:

Researchers discover first evidence indicating dinosaur respiratory infection

Sauro-throat, Part 3: what does Dolly’s disease tell us about sauropods?

Giant Dinosaur Had 2 Tumors on Its Tailbone

Dinosaurs got sick, too–but from what?

cough cough:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

This week we have a dinosaur episode, but not one you may expect. We’re going to learn about some dinosaur fossils found with evidence of sickness to answer the question, did dinosaurs get sick? Yes, they did. Otherwise this episode would be about two minutes long.

I know some people get squicked when they hear about illness and disease, so I’ve also unlocked a Patreon episode about puppies that are born green. Don’t worry, the puppies are fine! There’s a link in the show notes so you can click through and listen to the episode on your browser, no login needed.

Before we get to the dinosaurs, we have a birthday shout-out! Happy birthday to Gwendolyn, who is turning two years old this week! Oh my gosh, Gwendolyn, you’re going to learn so many new things this year! I hope you have a wonderful birthday.

And now, the dinosaurs.

Just a few days ago as this episode goes live, researchers announced that they’d found the fossilized remains of a young sauropod dinosaur. It lived around 150 million years ago in what is now the United States, specifically in southwestern Montana. The fossil was nicknamed Dolly by the paleontologists who studied it.

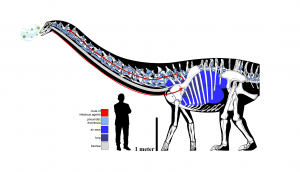

Dolly was a sauropod in the family Diplodocidae, and like other sauropods the Diplodocids all had huge neck vertebrae because their necks were so long. The bones weren’t solid, though, but contained air sacs that made the bones lighter and also connected to the respiratory system. This is the case in birds too. Technically the air sacs in the bones are called pneumatic diverticula, but that’s hard to say so I’m just going to call them air sacs.

When a bird breathes, instead of its lungs inflating and deflating, the air sacs throughout its body and bones inflate and deflate. This pumps fresh air through the lungs and allows the bird to absorb a lot more oxygen with every breath than most mammals can.

The bones of Dolly’s neck had unusual bony protrusions around the spaces where the air sacs once were. When the paleontologists made a CT scan of the protrusions they discovered they were abnormal bone growths that probably resulted from an infection. Sauropods share a common ancestor with birds and researchers think they might have sometimes caught a respiratory illness similar to aspergillosis [asper-jill-OH-sus], a disease common in birds and reptiles today.

Dolly would have had a fever, difficulty breathing, coughing, a sore throat, and other symptoms familiar to us as flu-like or pneumonia-like. Aspergillosis can be fatal in birds, so this respiratory infection might have actually been what killed Dolly. I think we can all agree that the worst symptom to have as a sauropod, whose necks were as much as 30 feet long, or 9 meters, is a sore throat.

That’s not the only indication of illness in a dinosaur fossil, of course. A 2003 paper published in Nature detailed the results of a study where paleontologists scanned 10,000 dinosaur vertebrae from over 700 animals to see if any of them showed tumors. They found 97 individuals that did, all of them from around 70 million years ago and all of them hadrosaurs. Those are the duck-billed dinosaurs that were common in the late Cretaceous in many parts of the world, especially in what is now North America and Asia. Hadrosaurs had flattened snouts that made the skull look like it has a duck bill, but it wasn’t a birdlike bill and hadrosaurs had teeth.

The hadrosaur was a plant-eater and it especially liked to eat conifers. Conifers were really common through most of the Cretaceous and are still around today, including pines, cedars, junipers, hemlocks, redwoods, yews, cypresses, larches, spruces, and more. Most are fast-growing evergreens with scaly or needle-like leaves, and many of them produce resins that are high in toxins to help ward off insects and fungus, and help keep many animals from eating the leaves. Amber is fossilized resin from conifer trees.

Conifer resins contain carcinogenic chemicals, which means that eating enough conifer leaves can increase the risk of developing tumors. Hadrosaurs ate conifers all the time, so it’s not surprising that the 2003 study found a relatively high percentage of hadrosaur vertebrae with tumors. Most of the tumors were small and benign. Only two dinosaurs showed evidence of cancerous tumors. Most confusing to the researchers is that the tumors are mostly in the hadrosaurs’ tail vertebrae.

A more recent study, from 2016, found two tiny tumors on one vertebra from a titanosaur. It lived 90 million years ago in what is now Brazil in South America. Titanosaurs are some of the largest sauropods known, including one species that was 85 feet long, or 26 meters, but the tumors were only about 8 millimeters across and were benign. This was the first study that found a tumor in a dinosaur that wasn’t a hadrosaur, although they’ve been found in fossils of other animals like mosasaurs and ancient crocodiles.

A study published in 2020 found advanced cancer in the leg bone of a centrosaurus too. Centrosaurus was a ceratopsian dinosaur that lived in the late Cretaceous in what is now Canada. It had a single horn on its nose, two smaller horns over its eyes, and a frill at the back of its head that was decorated with two more small hook-like horns. It lived in herds and ate plants. The individual with the cancerous leg bone would have had trouble running or even walking on its bad leg, but it didn’t die of cancer or predation. Instead, researchers think it drowned in a flood along with the rest of its herd. This means it was protected by its herd and able to live a normal life despite its disease. In fact, when the centrosaurus bone was first discovered, researchers thought it just showed a healed fracture.

That’s the case for a disease seen in some theropod dinosaurs, specifically tyrannosaurids, including Tyrannosaurus rex. Even Sue the T. rex shows evidence of this disease and researchers think it might have been wide-spread among tyrannosaurids. Initially paleontologists thought it was the result of bite wounds from other dinosaurs, but a 2009 study presented evidence that the lesions seen in many tyrannosaurid skulls were due to a parasitic infection similar to that found in some birds today.

The infection is called trichomonosis and is especially common in pigeons, where it’s called canker, and birds of prey, where it’s called frounce. Other birds can catch it too and it can decimate songbird populations. It’s due to a parasite that only affects birds, so you can’t catch it from a sick bird. If you have a birdfeeder or birdbath in your yard, it’s a good idea to give it a good scrub every so often and let it dry out thoroughly before putting it out again in a different area. The parasite is spread from bird to bird and causes lesions in the mouth and throat that can eventually cause the bird to die.

Researchers think trichomonosis in tyrannosaurids was spread not only between individuals when fighting, but the parasite might have been present in other dinosaurs that tyrannosaurids typically killed and ate. The parasite might not have caused symptoms in other dinosaurs, but when a tyrannosaurid was infected, the parasite completed its life cycle in its host. Other researchers think tyrannosaurids practiced cannibalism, which would also spread the parasite. The parasite actually feeds on the infected animal’s jawbone, causing erosive lesions in the mouth and throat which can stop a bird from being able to swallow, so researchers think many tyrannosaurids died of it the same way birds do.

A 2011 study of a reptile called Labidosaurus, which lived about 275 million years ago in the midwestern United States, showed a bacterial infection in the jaw bone that was the equivalent to an abscessed tooth. Labidosaurus grew about a foot long, or 30 cm, and looked like a lizard with a wide head. It lived long before dinosaurs evolved. This specimen is the first fossil ever found that shows a bacterial infection in a land-dwelling animal. The reptile had bitten something that caused it to lose two teeth, and as the injury healed over, bacteria were trapped inside the jaw. This led to a bad bone infection that was still active when the animal died, although researchers aren’t sure if the infection caused the animal’s death or not.

Most diseases don’t leave any evidence in bones, so we don’t have a fossil record of them. Since all animals get sick sometimes, it’s certain that dinosaurs had various diseases too. Next time you get a sore throat, just be glad that your throat isn’t as long as a sauropod’s.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. If you like the podcast and want to help us out, leave us a rating and review on Apple Podcasts or Podchaser, or just tell a friend. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us for as little as one dollar a month and get monthly bonus episodes.

Thanks for listening!