Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 15:32 — 17.8MB)

This week we have a two-ghost rating for our episode about dinosaur mummies! It’s a little spooky because we talk about mummies, but it’s mostly an episode about dinosaurs, which are not spooky.

Further reading:

Dinosaur Mummy Found with Fossilized Skin and Soft Tissues

Dakota the Dinomummy: Millenniums in the Making

Spectacularly Detailed Armored Dinosaur “Mummy” Makes Its Debut

Was a Dinosaur Mummy Dubbed ‘Appalachiosaurus’ Found in Tennessee?

An Edmontosaurus mummy found in 1908:

A 3D model of Dakota’s skin [photo from third link above]:

The Nodosaurid ankylosaur mummy:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

It’s monster month and this week we’ve got a monster from ancient times—really ancient times. We’re talking about mummies today, DINOSAUR mummies! On our spooky scale, this one rates two ghosts out of five since we do talk about mummies, but it’s not too spooky because we mostly talk about dinosaurs!

A dinosaur named Tarbosaurus lived around 70 million years ago in what is now Mongolia. It was probably closely related to Tyrannosaurus rex and would have looked very similar, with a big strong body but teeny-tiny front legs. Its front legs were even smaller than T. rex’s in relation to its body. It grew up to about 33 feet long, or 10 meters, and probably stood about 10 feet high at the hip, or 3 meters, and its big head had a big mouth full of really big teeth. It probably killed and ate hadrosaurs, sauropods, and other big dinosaurs. Some scientists think it was so closely related to T. rex that it should be classified as another species in the genus Tyrannosaurus.

We have quite a few Tarbosaurus fossils, including some very well-preserved skulls, so we know quite a bit about it. It had a good sense of smell and good hearing, but its vision wasn’t all that great. Some paleontologists think it might have been nocturnal. We’ve also found lots of bones of big dinosaurs with bite marks from teeth the size and shape of Tarbosaurus’s.

In 1991, though, a team of scientists found something even more incredible. They found a partial skeleton of a Tarbosaurus with lots of skin impressions. In short, they’d sort of found a mummified dinosaur. (It’s not really a mummy.)

The mummy consisted of the back end of the dinosaur, including the pelvis, tail, and hind legs. It had fallen onto sandy sediment that was especially fine-grained, so when the sediment transformed into sandstone over many millennia, it retained an exceptionally clear impression of the skin, including every small pebbly scale.

The expedition members took pictures and measurements, but they didn’t collect the specimen. Another expedition returned to the area to do so in 1993, but by then the specimen was gone. It was probably stolen by fossil poachers, who probably didn’t even realize the skin impressions were far more valuable than the bones and may have destroyed them while removing the skeleton.

The lost Tarbosaurus specimen is called a fossilized mummy since a dead animal’s skeleton with skin is sort of like a mummy. When the soft tissues of a dead animal or person are preserved in some way that causes them to stop decaying, that’s considered a mummy, and there are a lot of causes.

The most famous mummies, of course, are from ancient Egypt. It was important in Egyptian culture at the time to preserve a dead person’s body, and dead animals were also mummified sometimes, especially cats. The body was treated with salt and spices that helped dry the tissues and preserve them from bacteria, and once it was fully dehydrated the body was wrapped in linen bandages, covered with a natural waterproofing material made from plant resins, and placed in a wooden coffin. Sometimes the coffin was then put into a stone sarcophagus to keep it extra safe.

Other cultures across the world have practiced mummification too, and sometimes mummification happens naturally. This mostly happens in deserts and other dry areas, or in places where it’s very cold and the body freezes before it can decay, then dries out slowly. Sometimes a body is preserved after it’s buried, when the soil of the grave or the conditions in an underground crypt are just right, although bodies found in bogs are mummified too since bogs lack oxygen and that stops the decay of soft tissues.

Another dinosaur mummy was found in 1910 in the western United States, in Wyoming. It’s an Edmontosaurus specimen that’s remarkably well preserved and nearly complete, including skin impressions and even the horny beak. Initially the scientists who studied the animal thought the stomach contents had been preserved too, but more modern studies have concluded that the plant material was probably deposited in the body cavity after death. The dinosaur died near water and flooding may have washed plants into the partially decomposed carcass. There was even a little fish among the plant material, which was probably already dead when it was washed into the body cavity.

Edmontosaurus lived in what is now North America around 67 million years ago, surviving right up to the extinction event that killed off the non-avian dinosaurs. It’s one of many species of hadrosaurid, which are often called duck-billed dinosaurs. It could grow up to 39 feet long, or 12 meters, and possibly larger, and it was relatively common throughout its range. It probably walked on all fours most of the time but could stand or walk on its hind legs only, when it wanted to. It ate plants and may have migrated long distances to find food. It probably lived in groups.

The skin impressions of the 1910 specimen were impressive, but it isn’t the only edmontosaurus mummy ever found. We have several, in fact. The earliest was found in 1908, known as specimen AMNH 5060, and it was discovered by a man named Charles Sternberg and his three sons, who all three became paleontologists later in life. They were hoping to find a good triceratops skull to sell to a museum, but they found something even better when one of the sons realized the dinosaur they were uncovering was wrapped in skin impressions.

AMNH 5060 had died in an area that was very dry, so instead of rotting away, all the moisture in the body dried out and the skin remained stretched across the bones. It was essentially a natural mummy at that point. Then, as in the 1910 specimen, flooding probably covered the dead animal with sediment that preserved it in fine detail. Not only is the skeleton mostly intact, it’s also articulated so that the fossilized body parts are in the same places they were when the animal died, instead of having been scattered around after death.

More edmontosaurus mummies were found later, too, but it wasn’t until 2006 when the most important find so far was discovered in North Dakota, part of the United States. It isn’t just skin impressions we have from this specimen, which is nicknamed Dakota. We have actual fossilized skin and muscles and tendons, along with bones.

Dakota was discovered by Tyler Lyson on his uncle’s ranch when he was still in high school. He knew the dinosaur was there but he didn’t realize how important the find was until five years later when he was a paleontology student. The specimen was excavated in 2006 and was identified as an adolescent edmontosaurus that died about 67 million years ago. It was recently given a new 3D scan and results will hopefully be published soon, letting us all know if there are any fossilized organs inside the body.

Because so much of the soft tissues were preserved in place, we know a lot about how edmontosaurus looked when it was alive. For instance, the intervertebral discs that act as little shock absorbers between vertebrae are still in place, which means we know exactly how long Dakota was when it was alive, about 40 feet long, or 12 meters. Because so many of its tendons and muscles are preserved, scientists can calculate how fast it could run. Dakota could probably run 28 mph, or 45 km/hour. We even have a clue about Dakota’s pattern, if not its coloration. Differences in scale size and texture suggest that the dinosaur might have had stripes on at least part of its body.

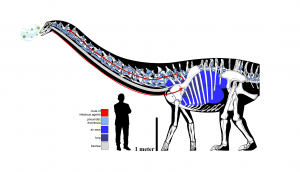

Edmontosaurus fossils aren’t the only dinosaur mummies, though. In 2011, an amazing ankylosaur fossil was discovered in a Canadian mine. Ankylosaurs had short legs and wide bodies covered in armor, and while some had club-like tails, Nodosaurids had regular tails but spikes on their backs that pointed sideways. The Canadian ankylosaur mummy is a nodosaurid.

Researchers think the dinosaur was probably caught in a flash flood, which swept it out to sea. It probably swam as long as it could, but its armored body made it heavy and it eventually drowned. Its body sank into the bottom sediment, which protected it from decay, scavengers, weathering, and other things that might have destroyed it. 110 million years later, an equipment operator fortunately noticed how weird the rock was that he’d just uncovered, and the world now has an amazing idea of what a living ankylosaur looked like.

The animal’s armored plates from the front of its body, some skin, and even its stomach contents are beautifully preserved, and the body is still articulated. It looks like it lay down to sleep and turned to stone. Some chemical pigments called melanosomes were discovered during study of the skin, which suggests that its skin was probably reddish-brown in color with a lighter-colored belly. It had massive spikes on its shoulders and along the sides of its neck, along with the smaller osteoderms that made up its armor on the rest of its body.

We know it mostly ate ferns because that was mostly what was in its stomach when it died. There was also some charcoal in its stomach, and researchers think it was probably eating ferns that had grown in an area where a wildfire had been recently. The ferns are so well preserved that scientists can determine their stage of growth, which means the dinosaur probably died in early to mid-summer.

Another dinosaur mummy is a Brachylophosaurus nicknamed Leonardo. Leonardo was found in July 2000 and wasn’t full grown when it died, only maybe three or four years old. Its skin and some of its internal organs are fossilized, and 3D scans have allowed scientists to learn a lot about it.

Brachylophosaurus was a hadrosaurid that lived around 80 million years ago in North America, and it could grow up to around 36 feet long, or 11 meters. It may have lived and migrated in groups. It had a flat crest on its head and a frill down the back, although some individuals had big crests and some had small ones. Paleontologists think big crests might have been a trait found only in males or only in females, we’re not sure which.

It ate plants, and we know from studies of Leonardo’s fossilized digestive system that it had eaten a lot of ferns right before it died, as well as leaves and other material from ancient relatives of conifers and magnolias. It also had worms. That’s right, even the parasites in Leonardo’s digestive system were fossilized. They were needle-like bristly worms who left more than 200 tiny burrows in the digestive lining, fossilized for eternity. Leonardo also had an internal pouch in its neck that was similar to a modern bird’s crop, where food was stored immediately after swallowing and where the digestive process may have started.

We’ll finish by talking about a story from April 2022, which discusses a dinosaur mummy found in my own state of Tennessee. The dinosaur was called Appalachiosaurus and was at least 77 million years old, and its skin and even some of its internal organs were reportedly intact—so much so that DNA was able to be extracted from them. The problem is that this particular story was posted to Facebook on April 1, also known as April Fool’s Day, and yes, it was a hoax. But Appalachiosaurus is a real species of dinosaur, a theropod that grew at least 21 feet long, or 6.5 meters, and probably quite a bit longer since the most complete specimen found so far is a juvenile. We don’t know a lot about Appalachiosaurus since only a few partial remains have ever been discovered. It would be fantastic if a fossilized mummy of one really did turn up one day.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. If you like the podcast and want to help us out, leave us a rating and review on Apple Podcasts or Podchaser, or just tell a friend. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us for as little as one dollar a month and get monthly bonus episodes.

Thanks for listening!