Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 16:28 — 18.3MB)

Thanks to William who suggested we talk about the Loch Ness Monster for our big Halloween episode!

Further reading:

1888 (ca.): Alexander Macdonald’s Sightings

1933, July 22: Mr. and Mrs. George Spicer’s Loch Ness Encounter

The 1972 Loch Ness Monster Flipper Photos

White Mice, Bumblebees, and Alien Worms? Unexpected Mini-Monsterlings in Loch Ness

Further watching:

1933 King Kong clip: Brontosaurus attack!

The following stills are from the above King Kong clip:

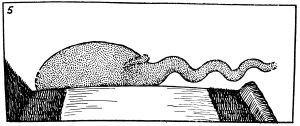

The drawing by Rupert T. Gould for his 1934 book about the Loch Ness Monster. He drew it after interviewing Mr. Spicer about his 1933 sighting:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

This week is our big Halloween episode to finish off monster month! I hope your October has been amazing and you have fun plans for Halloween. William suggested we learn about the Loch Ness Monster, so let’s go!

We talked about the Loch Ness Monster, AKA Nessie, a really long time ago, back in episode 29. Those old episodes aren’t even available in the feed anymore—you have to go to the website to find them, and the audio isn’t very good. So here’s a revised and updated Nessie episode! There are some spooky stories associated with this one, but not too scary. Let’s call it one and a half out of five monsters on the spooky scale.

First, a little background about what Loch Ness is. It’s the biggest of a chain of long, narrow, steep-sided lakes and shallow rivers that cut the Scottish Highlands right in two along a fault line. Loch Ness is 22 miles long, or 35 km, with a maximum depth of 754 feet, or 230 meters, the biggest lake in all of the UK, not just Scotland.

During the Pleistocene, or ice age, Scotland was repeatedly covered with glaciers and ice sheets that were almost a kilometer thick. The ice only completely melted about 8,000 years ago. The massive weight of the glaciers over the fault line, where the rocks are already weaker, started the process of carving out the lake, and when the ice started melting in earnest around 10,000 years ago, the massive amounts of meltwater washed the weakened rocks out and left the deep valley that is now Loch Ness. The land slowly rose from where the ice had pressed it down, so that Loch Ness is now about 50 feet above sea level, or 15 meters. In other words, Loch Ness is only about 10,000 years old.

All the lochs and their rivers have made up a busy shipping channel since the Caledonian Canal made them more navigable with a series of locks and canals in 1822, but the area around Loch Ness was well populated and busy for centuries before that. It’s a beautiful area, so Loch Ness has also long been a popular tourist destination, well before the Nessie sightings started.

There have been stories of strange creatures in Loch Ness and all the lochs, but nothing that resembles the popular idea of Nessie. The stories were mostly of water monsters of Scottish folklore, like the kelpie we talked about in episode 351, or of out-of-place known animals like a bottle-nosed dolphin that was captured at sea and released in the loch as a prank in 1868.

The oldest monster report in the area actually comes from the 7th century, but it’s supposed to have happened in the River Ness, which drains from the lake. When local people told St. Columba about a monster that had grabbed a man swimming in the River Ness, and presumably ate him, the saint went there to take care of the monster. He told one of his followers to swim across the river, which sounds pretty rough, but the saint said, “Don’t worry, fam, I gotchu,” but in old-timey language. The man started swimming and sure enough, a water beast approached. The saint made the sign of the Christian cross and said, “Stop right there, don’t touch him. Get back, monster!” The monster swam away immediately and was never seen again.

The next sighting important enough for people to write down happened more than 1,400 years later, in 1933. The newspaper Inverness Courier printed a sighting by a woman named Aldie Mackay, who saw something that looked like a whale rolling around in the lake while she looked out the car window as her husband drove. Her husband saw it too.

Mackay’s sighting happened in mid-April of 1933 and the report appeared in May. But the big sighting that pretty much everyone has heard about happened two months later, in late July. It’s sometimes reported as an August sighting because the initial report appeared in the Inverness Courier on August 4, 1933.

A couple on holiday from London, Mr. and Mrs. George Spicer, reported seeing a large creature crossing the road around 50 meters in front of their car. In his initial report, Mr. Spicer described it as grayish with a thick body and a long neck, moving jerkily. The neck twisted and moved up and down. He didn’t see legs or a tail, but thought that a flopping movement around the downward slope of the body toward the neck might be the end of the tail, curved around the body. Mrs. Spicer disagreed and thought it was a small animal being carried at its shoulder.

Mr. Spicer initially described the monster as being about 6 to 8 feet long, or 1.8 to 2.4 meters, because, he said later, he was worried about accidentally exaggerating the size. Later, after he returned to look at the road again, he realized the monster had to have been around 25 feet long, or over 7.5 meters, since it was longer than the road was wide and its front and back ends were hidden in the trees on either side.

By the time the Spicer’s car reached the monster, it had already disappeared down the slope toward the lake, although neither witness actually saw it in the water. Mr. Spicer said that the monster actually looked like “a huge snail with a long neck.”

The Spicers didn’t stop where they saw the monster, but shortly later they stopped and talked to a man on a bicycle, telling him what they’d seen. The man must have read about the April sighting, or heard about it, because he told the Spicers that there were other recent monster reports around Loch Ness.

But something else featuring monsters happened in April of 1933. The movie King Kong was released in the first week of April, before the Spicer sighting and only a few days before the Aldie Mackay sighting. In addition to the giant gorilla King Kong, the movie featured dinosaurs, including a brontosaurus that attacks some people on a raft. Like the other monsters in King Kong, the brontosaurus was filmed using stop-motion animation, where a model is moved small increments, photographed, moved a little more, photographed again, and so on, so that when the photos are put together into a film, the model appears to move. This is how Wallace and Gromit is animated, and some old holiday specials like Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer. It’s done well in King Kong, but the movements are a little jerky. To make the model look more realistic, the dinosaur was obscured by fog and trees in many scenes. It also emerges initially from the water and pursues the men onto land.

Spicer admitted in an interview a few months after his sighting that he had seen King Kong and that his monster strongly resembled the dinosaur in the movie. It’s possible that he and his wife really did see something crossing the road that they couldn’t identify, and that their memories of the King Kong dinosaurs filled in the gaps of what they couldn’t actually see. Remember that Mr. Spicer described the animal as moving jerkily with its neck moving up and down and twisting, something that also happens in the movie. He didn’t see any legs, and most of the time in the movie the brontosaurus’s legs are hidden or mostly hidden.

After the Spicer sighting, lots of previous monster sightings were reported. For instance, the Northern Chronicle newspaper printed a letter it received about an 1888 sighting, or sightings. A man named Alexander Macdonald traveled on the mail steamer pretty frequently, and he often saw what he said looked like a stubby-legged, really big salamander in the water. But by 1933 Macdonald was long dead, so no one could ask him if the letter-writer maybe just made it all up.

One good thing has come from Nessie’s popularity. Loch Ness has been studied far more than it would have been otherwise. The water is murky with low visibility, so underwater cameras aren’t much use. However, submersibles with cameras attached have been deployed many times in the loch. In 1972 a dramatic result was reported, with a clearly diamond-shaped flipper photographed from a submersible, but it turned out that the flipper was basically painted onto two photos that otherwise show nothing but the reflection of light on silt or bubbles.

Sonar scanning has been done on the entire lake repeatedly, in 1962, 1968, 1969, twice in 1970, 1981 through 1982, 1987, 2003, and 2023. They found no gigantic animals. The 1987 scan resulted in three hits of something larger than the biggest known salmon in the loch, but much smaller than a lake monster. It’s possible that the hits were only debris such as sunken boats or logs. From all the scans, though, we know there are no hidden outlets to the sea under the lake’s surface.

There are lots of known animals in and around the loch, from salmon to otters, and lots and lots of birds. Seals frequently visit, coming up the shallow River Ness through its locks. Any of these animals, especially the seals, may have contributed to Nessie sightings over the years, together with boats seen in the distance and floating debris such as logs. The lake doesn’t contain enough fish to sustain a population of large mystery animals even if they had somehow eluded all those sonar scans. No bones or dead bodies have been found, and no clear photographs have ever been taken of an unknown animal.

In the 1970s the idea that sightings of the Loch Ness Monster might actually be sightings of unusually large eels became popular. A 2018 environmental DNA study brought the idea back up, since the study discovered that there are a whole, whole lot of eels in Loch Ness. The estimate is a population of more than 8,000 eels in the loch, which is good since the European eel is actually critically endangered. But most of the eels found in Loch Ness are smaller than average, and the longest European eel ever measured was only about 4 feet long, or 1.2 meters. An eel can’t stick its head out of the water like Nessie is supposed to do, but it does sometimes swim on its side close to the water’s surface, which could result in sightings of a string of many humps undulating through the water.

There are also lots of suggested weather and water conditions in Loch Ness that could make people believe they’d seen a monster, from rare mirages to less rare standing waves. But whatever Nessie really is, there is a mystery animal in Loch Ness. It’s just not very exciting so very few people have heard of it.

A 1972 search for Nessie by the same team that announced that famous underwater photograph of a flipper, which later turned out to be mostly painted on, filmed something in the loch that wasn’t just paint. They were small, pale blobs on the grainy film. The team called them bumblebees from their shape.

Then in July of 1981, a different company searching not for Nessie but for a shipwreck from 1952, filmed some strange white creatures at the bottom of the loch. One of the searchers described them as giant white tadpoles, two or three inches long, or about 5 to 7 cm. Another searcher described them as resembling white mice but moving jerkily.

The search for the wreck lasted three weeks and the white mystery animals were spotted more than once, but not frequently. Afterwards, the company sent video of them to Dr. P Humphrey Greenwood, an ichthyologist at the Natural History Museum in London. Since this was the 1980s, of course, the film was videotape, not digital, but Dr. Greenwood got some of the frames computer enhanced. The enhancement showed that the animals seemed to have three pairs of limbs and Dr. Greenwood tentatively identified them as bottom-dwelling crustaceans, but not ones native to Loch Ness. A few years ago, zoologist Karl Shuker suggests they might be some kind of amphipod.

Amphipods are shrimp-like crustaceans that live throughout the world in both the ocean and fresh water, and most species are quite small. While they do have more than three pairs of legs—eight pairs, in fact, plus two pairs of antennae—the 1981 video wasn’t of high quality and details might easily have been lost. Some of the almost 10,000 known species of amphipod are white or pale in color and grow to the right size to be the ones filmed in Loch Ness. But no amphipods of that description have ever been caught in Loch Ness.

New amphipods are discovered all the time, of course. They’re simply everywhere, and the smallest species are only a millimeter long. But because they’re so common, it’s also easy to transport them from one body of water to another. It’s possible that the white mice crustaceans in Loch Ness traveled there on a monster hunter’s boat.

If you’re lucky enough to visit Loch Ness, definitely bring your binoculars just in case you see something big in the water. But keep your scientist hat on too, because it’s more likely that you’ll see a floating log or stump, a big fish, an anomalous wave causing an optical illusion, or some other reasonable explanation for the sighting. But you never know! Happy Halloween!

You can find Strange Animals Podcast at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us for as little as one dollar a month and get monthly bonus episodes.

Thanks for listening!