Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 9:44 — 10.8MB)

This week we take a look at some of the many animals that were discovered last year!

Further reading:

‘Blob-Headed’ Catfish among New Species Discovered in Peru

New Species of Dwarf Deer Discovered in Peru

Hylomys macarong, the vampire hedgehog

Hairy giant tarantula: The monster among mini tarantulas with ‘feather duster’ legs

Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution and partners discover new ocean predator in the Atacama Trench

Never-before-seen vampire squid species discovered in twilight zone of South China

The blob headed catfish [photo by Robinson Olivera/Conservation International]:

A new mini tarantula [photo by David Ortiz]:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

This week is the 8th year anniversary of this podcast, so thanks for listening! It’s also our annual discoveries episode, where we’ll learn about a few animals that were discovered last year–in this case, in 2024.

Let’s start in Peru, a country in western South America. A 2022 survey of organisms living in the Alto Mayo region was published at the very end of 2024, revealing at least 27 new species and potentially more that are still being studied. One of those new species is a fish called the blob headed catfish.

The new fish has been placed in the bristlemouth armored catfish genus, but as you can probably guess from its name, it has a big blobby head and face. Scientists have no idea why it has a blob head. It lives in mountain streams and that’s about all we know about it right now.

Another animal found in the same survey is a new mouse. It lives in swampy forests and is semi-aquatic, including having webbed toes. It’s dark gray in color and is probably closely related to the Peruvian fish-eating rat, which is mostly brown in color and was only described in 2020.

Another new species from Peru is a type of small deer, called a pudu, that has been named Pudella carlae. It’s one of those “hidden in plain sight” discoveries, because until 2024 it was thought to be the same as the northern pudu that also lives in Ecuador and Colombia. The new deer is only 15 inches tall, or 38 cm, and is dark brownish-orange in color with black legs and face. It only lives in Peru, mostly in high elevations. It’s also the first deer species discovered in the 21st century, although hopefully not the last.

While we’re talking about mammal discoveries, we have to talk about the vampire hedgehog just because of its name. It was actually described at the very end of 2023, but it’s such an interesting animal that we’ll say it’s a 2024 discovery.

The vampire hedgehog was actually discovered a whole lot earlier than 2023, but no one noticed it was new to science for a long time. A small team of researchers studying soft-furred hedgehogs decided to collect DNA samples from all the museum specimens they could find. One of the specimens was in the archives of the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, collected in 1961 but never studied. When the scientists compared its DNA to the other specimens they’d found, it didn’t match up. Not only that, a closer look showed that it had fangs. Naturally, they named it the vampire hedgehog and went searching for living ones.

The vampire hedgehog lives in parts of Vietnam and is a member of the soft-furred hedgehogs, also called gymnures, hairy hedgehogs, or moonrats. Instead of spines, moonrats have bristly fur and long noses that make them look like shrews, but hairless tails that make them look like rats. They’re not rodents but are closely related to other hedgehogs. They eat pretty much anything but especially like to eat meat. This includes mice and frogs, along with various invertebrates.

As for the vampire hedgehog’s fangs, both males and females have them, but males have bigger fangs. Scientists don’t know yet what the hedgehogs use their fangs for. It could be they help the animals keep a better hold on wiggly prey, but it could be the hedgehogs just think big fangs look good on other hedgehogs so they’re one way the animals decide on a mate.

Just a few weeks ago we talked about the biggest tarantula in the world, the goliath birdeater, but did you know that there are tiny tarantulas too? The genus Trichopelma contains miniature tarantulas with body lengths measured in millimeters, and a new one was described in 2024 from western Cuba. But the great thing is, this tiny tarantula is the largest of the two dozen species known. Of the four specimens found so far, the largest body length is 11.2 millimeters—a veritable giant among miniature tarantulas!

The new species has been named Trichopelma grande, and the males, at least, have been discovered in trap-door burrows in the ground. No female specimens have been observed yet. Ground-dwelling tarantulas usually have a lot less hair on their legs, while tarantulas that live in trees are the ones with especially hairy legs, but T. grande is ground-dwelling but has very hairy legs. Or at least the males do. We don’t know about females yet.

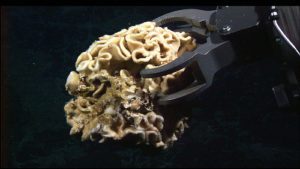

Now let’s talk about some ocean animals, and we have to go back to Peru for our first one. The Atacama Trench is also called the Peru-Chile Trench because it’s about 100 miles, or 160 km, off the coast of both countries. At this spot a continental plate in the ocean is pushing underneath the South American plate, and it’s incredibly deep as a result. It’s been measured as 26,460 feet below the ocean’s surface, or 8,065 meters. That’s five miles deep!

Not a lot of animals live near the bottom, where the water pressure is intense and there’s not much to eat, but little crustaceans called amphipods are fairly common in the trench. Amphipods are common animals throughout the world’s oceans and freshwater, with almost 10,000 species discovered so far. There’s even a terrestrial amphipod called the sandhopper. Amphipods look a little bit like tiny shrimp, although there are some giant species. Giant in this case means 13 inches long, or 34 cm, but most are like the miniature tarantulas and are measured in millimeters.

In 2023 a new amphipod was discovered near the bottom of the Atacama Trench, and it was described in 2024 as a new species in its own genus. It grows just over an inch and a half long, or almost 4 cm, and appears white because of its lack of pigment. And most interesting of all, it’s a predator that catches and eats other species of amphipod.

Our last 2024 discovery is one that I find extremely exciting. We talked about the vampire squid way way way back in episode 11, before some of my listeners were even born, and while it has the word squid in its name, it’s not exactly a squid. It’s also not exactly an octopus. It’s the last surviving member of its own order, Vampyromorphida, which shares similarities with both squids and octopuses. And as of 2024, the vampire squid is not the only member of its own order, because they’ve found a second vampire squid!

The vampire squid is a deep-sea animal that grows about a foot long, or 30 cm, and eats whatever organic material floats down from far above. That could mean part of a dead amphipod or it could mean fish poop, the vampire squid is not picky. The new species of vampire squid was found around 3,000 feet below the surface, or a little over 900 meters, in the South China Sea. A genetic study determined that it does seem to be a new species, and the scientific name Vampyroteuthis pseudoinfernalis has been proposed. The official description hasn’t yet been published, but that just means we’ll probably get to talk more about it in a future episode.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us for as little as one dollar a month and get monthly bonus episodes.

Thanks for listening!