Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 9:43 — 11.1MB)

Sign up for our mailing list! We also have t-shirts and mugs with our logo!

This week let’s learn about a weird marine worm and its extinct ancestor!

Further reading:

Eunice aphroditois is a rainbow, terrifying

The 20-million-year-old lair of an ambush-predatory worm preserved in northeast Taiwan

Here’s the money shot of the sand striker with its jaws open, waiting for an animal to get too close. The stripy things are antennae:

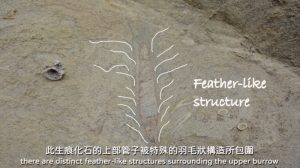

The fossilized burrow with notes:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

This week we’re going back in time 20 million years to learn about an animal that lived on the sea floor, although we’ll start with its modern relation. It’s called the sand striker and new discoveries about it were released in January 2021.

Ichnology is the study of a certain type of trace fossil. We talked about trace fossils in episode 103, but basically a trace fossil is something associated with an organism that isn’t actually a fossilized organism itself, like fossilized footprints and other tracks. Ichnology is specifically the study of trace fossils caused by animals that disturbed the ground in some way, or if you want to get more technical about it, sedimentary disruption. That includes tracks that were preserved but it also includes a lot of burrows. It’s a burrow we’re talking about today.

Because we often don’t know what animal made a burrow, different types of burrows are given their own scientific names. This helps scientists keep them organized and refer to a specific burrow in a way that other scientists can immediately understand. The sand striker’s fossilized burrow is named Pennichnus formosae, but in this case we knew about the animal itself before the burrow.

The sand striker is a type of polychaete worm, and polychaete worms are incredibly successful animals. They’re found in the fossil record since at least the Cambrian Period half a billion years ago and are still common today. They’re also called bristle worms because most species have little bristles made of chitin. Almost all known species live in the oceans but some species are extremophiles. This includes species that live near hydrothermal vents where the water is heated to extreme temperatures by volcanic activity and at least one species found in the deepest part of the ocean that’s ever been explored, Challenger Deep.

A polychaete worm doesn’t look like an earthworm. It has segments with a hard exoskeleton and bristles, and a distinct head with antennae. Some species don’t have eyes at all but some have sophisticated vision and up to eight eyes. Some can swim, some just float around, some crawl along the seafloor, and some burrow in sand and mud. Some eat small animals while others eat algae or plant material, and some have plume-like appendages they use to filter tiny pieces of food from the water. Basically, there are so many species known—over 10,000, with more being discovered almost every year, alive and extinct—that it’s hard to make generalizations about polychaete worms.

Most species of polychaete worm are small. The living species of sand striker generally grows around 4 inches long, or 10 centimeters, and longer. We’ll come back to its size in a minute. Its exoskeleton, or cuticle, is a beautifully iridescent purple. It doesn’t have eyes, instead sensing prey with five antennae. These aren’t like insect antennae but look more like tiny tentacles, packed with chemical receptors that help it find prey.

The sand striker lives in warm coastal waters and spends most of its time hidden in a burrow in the sand. It’s especially common around coral reefs. While it will eat plant material like seaweed, it’s mostly an ambush hunter.

At night the sand striker remains in its burrow but pokes its head out with its scissor-like mandibles open. When the chemical receptors in its antennae detect a fish or other animal approaching, it snaps its mandibles on it and pulls it back into its burrow. Its mandibles are so strong and sharp that sometimes it will cut its prey in half and then, of course, it pulls both halves into its burrow to eat. If the prey turns out to be large, the sand striker injects it with venom that not only stuns and kills it, it starts the digestive process so the sand striker can eat it more easily. It does all this so quickly that it can even catch fish and octopuses. The mandibles are at the end of a feeding apparatus called a pharynx, which it can retract into its body.

If a person tries to handle a sand striker, they can indeed get bitten. The sand striker’s mandibles are sharp enough to inflict a bad bite, and if it injects venom it can make the bite even more painful. Not only that, the sand striker’s body is covered with tiny bristles that can also inflict stings, with a venom strong enough that it can cause nerve damage in a human that results in permanent numbness where the person touched it. Don’t pet a sand striker.

Remember how I said the sand striker grows 4 inches or longer? That’s actually the low end of its size. The average sand striker is about 2 feet long, or 61 centimeters, but it can sometimes grow 3 feet long, or 92 centimeters, or even more. Sometimes a lot more.

In January 2009, someone noticed something in a float along the side of a mooring raft in Seto Fishing Harbor in Japan. The mooring raft had been in place for 13 years at that point and no one knew that a sand striker had moved into one of the floats. It had a nice safe home to use as a burrow. Sand strikers grow quickly and this one was living in a more or less ideal situation, so it just grew and grew until when it was found, it was just shy of 10 feet long, or 3 meters. Even so, it was still only about an inch thick, or 25 millimeters.

There are unverified reports of even longer sand strikers, some up to 50 feet long, or 15 meters. Look, seriously, do not pet it. Since sand strikers spend most of the time in burrows, it’s rare to get a good look at a full-length individual in the wild and we don’t know how long they can really get.

In case you’d forgotten, though, we started the episode talking about a fossilized burrow. In a fossil bed in northeast Taiwan, a team of paleontologists uncovered hundreds of strange burrows dating to about 20 million years ago. The burrows were L-shaped and as much as 6.5 feet long, or 2 meters, and about an inch across, or 2.5 centimeters. Even more confusingly, the fossilized sediment showed feather-like shapes in the upper section of the burrows.

The team of scientists studying the burrows had no idea what the feather-like structures were. The burrows were mysterious from start to finish anyway, since they were so much larger than most burrows in the seafloor.

They decided to do something unusual to solve some of the mysteries. They reached out not only to marine biologists but to marine photographers and aquarium keepers to get their insights. And, as you’ve probably guessed by now, the fossilized burrows most closely match those of the sand striker.

They even found out what the feather-shaped structures were. When a sand striker grabs a fish or other prey and drags it into its burrow, a lot of time it’s still alive, at least at first. Its struggles to get away can cause the sides of the burrow to shift. The sediment can’t collapse all the way because the worm lines it with mucus, so the partial collapsing and shifting results in feathery shapes.

These fossilized burrows are the first trace fossils known to be made by a marine ambush predator, which is pretty awesome. It’s even more awesome that some modern sand strikers are using the same type of burrows over 20 million years later.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. If you like the podcast and want to help us out, leave us a rating and review on Apple Podcasts or Podchaser, or just tell a friend. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us for as little as one dollar a month and get monthly bonus episodes.

Thanks for listening!