Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 7:49 — 9.2MB)

Thanks to Morgan for suggesting this week’s topic, the Antarctic Death Star!

Further reading:

Echinoderm Tube Feet Don’t Suck! They Stick!

Bodies of Starfish and Other Echinoderms Are Really Just Heads, New Research Suggests

The Antarctic death star [from first link listed above]:

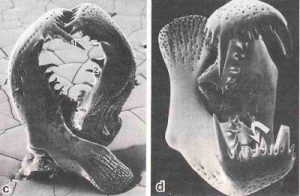

The “beartrap” structures, magnified [from first link listed above]:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

It’s been way too long since we talked about an invertebrate, so this week we’ll look at one suggested by Morgan, the Antarctic death star.

It has a lot of other names too, including the Antarctic sun starfish and the wolftrap or beartrap starfish. Its scientific name is Labidiaster annulatus. I’m going to call it the death star because I think that’s hilarious.

As you may have guessed from its common names, the Antarctic death star is a starfish that lives in cold ocean waters near the Antarctic, AKA the south pole. But its common names also hint at how it gets its food, and this would be a good time to take a moment and be glad you’re not a copepod that also lives in the Antarctic Ocean.

The death star is reddish-brown on its dorsal side, white underneath. It’s a large starfish, up to two feet across, or 60 cm, and it also has a lot of legs, more properly called rays—up to 50 of them. The rays are long, narrow, and very flexible, and the undersides have rows of little structures called tube feet. All echinoderms, including starfish, have these tube feet and they’re used for several purposes. One important purpose is helping the animal stick to a hard surface, which allows it to climb around more easily and right itself if it gets flipped over.

For over 150 years scientists thought the tube feet acted like little suction cups, but that didn’t explain how a starfish or other echinoderm could stick to porous surfaces. It wasn’t until 2012 that a study was published explaining how the tube feet actually work. The tube feet exude tiny amounts of a sticky chemical that acts like glue.

The death star’s body also has little spines and bumps all over it, but it also has some structures that give the animal its other names, the wolftrap or beartrap starfish. The structures are called pedicellariae [PED-uh-suh-LAIR-ee-aye], which are also common in echinoderms. Most echinoderms seem to use them to keep algae and other organisms from settling on the body, although scientists aren’t completely sure. Pedicellariae have muscles and sensory receptors, and when something touches them, they snap shut like a trap. In the case of the Antarctic death star, its pedicellariae are extra big and really sharp. When a krill or other tiny animal brushes against one of these little traps, it grabs the animal and then the death star can eat it.

But that’s just part of what’s going on when the death star goes hunting, so let’s discuss it in more detail.

Most starfish spend almost all their time on the ocean floor, walking around looking for food. The death star does this too, but not all the time. Quite often a death star will climb on top of a rock or other large structure, and then it will extend some of its rays up and out into the water. It waves its rays around and if it touches a small animal, it will wrap the rays around it. The pedicellariae also snap shut. Then the death star can eat whatever it caught. Usually this is krill or amphipods, but it’s not a picky eater. Since it will eat animals it finds already dead, researchers aren’t completely sure if the death star ever catches fish. They’ve certainly found dead fish in death star stomachs, but the water it lives in is so cold that not many fish live there anyway. Fish don’t make up a big part of the death star’s diet, whether or not it’s catching them itself. The death star also eats other starfish, including smaller death stars.

Like other starfish, the death star can eat surprisingly large pieces of food because it can evert its stomach. This means it can actually push its stomach out through its mouth and engulf whatever large food it’s found or caught. The digestion process starts right away, which allows the starfish to eat food that can’t actually fit through its mouth. It doesn’t chew its food because it doesn’t have any kind of teeth or jaws, but who needs teeth and jaws if your stomach can just reach out and grab food?

While I was researching the death star, I came across a study published in November 2023 about echinoderms, so let’s learn something surprising about starfish and their relations in general.

Echinoderms demonstrate radial symmetry instead of bilateral symmetry. That’s why you can’t tell when a starfish or other echinoderm is facing forward, because it doesn’t actually have a forward. But it’s actually more complicated than it sounds, because the distant ancestor of echinoderms, which lived during the Cambrian almost half a billion years ago, did demonstrate bilateral symmetry, and the larvae of modern echinoderms do too. When a modern echinoderm larva develops into an adult, the left side of its body is the only part that grows. The right side of its body is absorbed and from then on the body develops radially. It actually shows pentaradial symmetry, with five sections around the central part of the body. That’s why so many starfish have five rays, although obviously not all of them. The death star starts out with five rays but adds more and more as it grows.

For a long time scientists have wondered if echinoderms technically have heads or if they’re just bodies. They don’t have eyes or nostrils or most other body parts that we associate with the head, just an oral opening in the middle of the underside of the disc. Starfish do have cells at the ends of their rays that act as eyespots, which are sensitive to light and dark but can’t actually see anything else. Instead of a brain, it has a nerve ring around its mouth and connected nerve nets in its rays, and its digestive system extends into its rays.

In other words, it sure seems like an echinoderm has no head and is basically just a weird body. But the new study came to a surprising conclusion. The study examined starfish genetics and discovered that the genes associated with head development were there. It was the genes associated with the development of a body and tail that were missing. In other words, the starfish, and echinoderms in general, are just really complicated heads.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us for as little as one dollar a month and get monthly bonus episodes.

Thanks for listening!