Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 21:13 — 21.9MB)

Subscribe: | More

It’s October, MONSTER MONTH! We’re starting it off right with an episode about the Yeti! I literally could have made this episode an hour long without even touching on half the information out there, but no one wants to listen to me talk for that long. If you’re intrigued and want to hear more about our big furry friend from the Himalayas, check out the fine podcasts listed below.

The Himalayas, in map form:

A Himalayan brown bear (tongue blep alert!):

A bear standing up (this is a brown bear from Alaska but I like the picture. Bears stand up a lot):

Recommended listening:

Museum of Natural Mystery – episode 14: “Backtracking with Bigfoot” – highly recommended for information about North American bigfoot/Sasquatch lore and history. It’s family friendly and not very long. I heart it.

MonsterTalk – episode 116 “Yetipalooza” – lots of Yeti information and some terrible, terrible puns

Strange Matters Podcast – “Legendary Humanoid Creatures” – a good overview of a lot of different bigfoot type monsters, including the Yeti

Hidden Creatures Podcast – Episode Six A “Yearning for the Yeti’s Discovery” and Episode Six B “The Yeti…Again” – lots of info on the Yeti

All of the above should be family friendly, with possible mild language.

Resources/further reading:

The Historical Bigfoot by Chad Arment

Abominable Science! by Daniel Loxton and Donald R. Prothero

Hunting Monsters by Darren Naish

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

It’s October and that means monsters. Let’s jump right in with one of the biggest stars of cryptozoology, bigfoot!

As part of my research for this episode, I listened to other podcasts that have covered bigfoot and his kin. One of those was the Museum of Natural Mystery’s episode 14, Backtracking with Bigfoot. I was more than a little dismayed when I listened to that one, because it’s exactly what I had hoped to do with this episode. In fact, while Museum of Natural Mystery covers other topics than just animals, when they do focus on animals they scratch the same itch I created Strange Animals podcast to scratch. If I’d discovered them earlier, the podcast you’re listening to now would probably be about music or something, not animals.

There’s a link to Backtracking with Bigfoot in the show notes and I highly recommend you go listen to it. It focuses mainly on the Bigfoot phenomenon in North America, from Sasquatch to skunk apes. Rather than cover the same ground, my focus here is going to be on bigfoot legends from other parts of the world. There’s so much fascinating information out there that I had to break the episode into two parts. This week we’re looking at the yeti.

But first, some background. There are a couple of starting places for the modern concept of bigfoot. In 1921, the Everest Reconnaissance Expedition found tracks in the snow resembling a bare human foot. They realized the tracks were probably made by wolves, the front and rear tracks overlapping and the snow melted enough to obscure the paw pads. Expedition leader Charles Howard-Bury wrote that the expedition’s Sherpa guides claimed the tracks were made by a wild hairy man.

At about the same time, the 1920s, British Columbian schoolteacher John W. Burns was collecting reports of Native encounters with giant wild people. He coined the term Sasquatch by anglicizing a couple of different words from several different Native dialects.

Burns published his stories in magazines. Howard-Bury talked to reporters about his Everest expedition. The idea of bigfoot took shape and took off in the public imagination. It merged with giant apes and ape-men in popular culture, like King Kong in 1933 and the movie Tarzan the Ape Man in 1932, both of which were huge hits.

Before this, from the early 19th century to around the 1940s, newspaper reports that would today be called bigfoot sightings were attributed to wild men or occasionally to escaped gorillas or other apes. Some were hoaxes, some seem to concern real humans living outside of society, and some are probably misidentifications of bears and other real animals. Very few suggest the wild man in question was a creature unknown to science. This doesn’t mean there aren’t any legit sightings of an actual bigfoot mixed in, just that bigfoot wasn’t yet a common concept.

But by 1967, year of the famous Patterson-Gimlin film, the notion of bigfoot as a huge, hairy, upright ape was firmly planted in western culture. Most of us know a fair amount about North American Sasquatches just from popular culture. ‘Squatch-hunters on TV stumble around in the woods at night, which by the way I never understood since apes are not nocturnal. Bigfoot appears in TV commercials, movies, and is the subject of documentaries that are all pretty much identical. But most of us are less familiar with the Yeti.

The English-speaking world first learned about the Yeti after a 1921 expedition to Mount Everest. As I mentioned a few minutes ago, the expedition members recognized that a line of huge human-like prints they spotted in the snow above 20,000 feet probably belonged to wolves or some other four-legged animal. The forepaw and hind paw prints overlapped, making a double track of what looked like long, relatively narrow footprints. Then the snow partially melted, obscuring the details and enlarging the prints. Colonel Howard-Bury, the expedition leader, was very clear about this in the London Times in October 1921, and dismissed as superstition the Sherpas’ statement that the tracks belonged to a hairy wild man.

Maybe all that was true, but if you’re a journalist hoping to sell papers, which story are you going to run with? After the expedition returned to India, journalist Henry Newman interviewed the porters and published a sensational account of their stories. He translated their name for the wild man, Metoh kangmi, as “abominable snowman.” Maybe you’ve heard of it.

As it turns out, Metoh kangmi means something closer to man-bear. In fact, it means man-bear, man-bear, because both mi-te and kangmi mean the same thing.

The peoples who live in and around the Himalayas speak a lot of different languages. They also have a lot of different names for what we call the Yeti. Yeti is a corruption of a Sherpa term, yeh-teh, meaning “animal of rocky places,” although it may be related to the term meh-teh, which means man-bear. Other terms translate to wild man, cattle bear, brown bear, and white bear. I’m going to refer to all these creatures as the Yeti for convenience sake.

While the pop culture version of the Yeti is a white bigfoot striding through the snow, actual sightings of Yetis are of brown, black, or even reddish creatures. Local Yeti lore throughout the Himalayas doesn’t describe a specifically upright apeman or even a particularly human-like monster, either. To locals, yetis are fairly amorphous, and when they are described, they tend to have bear-like or even big-cat-like characteristics.

As an example, here’s a quote from one of the earliest Yeti reports, from 1889. I’m taking the quote from the book Abominable Science by Daniel Loxton and Donald Prothero. Links to all the books I used in my research are in the show notes, of course. Anyway, the quote itself comes from a book called Among the Himalayas by Laurence A. Waddell:

“Some large footprints in the snow led across our track, and away up to higher peaks. These are alleged to be the trail of the hairy wild men who are believed to live amongst the eternal snows, along with the mythical white lions, whose roar is reputed to be heard during storms. The belief in these creatures is universal among Tibetans. None, however, of the many Tibetans I have interrogated on this subject could ever give me an authentic case. On the most superficial investigation it always resolved itself into something that somebody heard tell of.”

Waddell goes on to declare that the wild man was nothing more than a bear, then says that the people of the area are just superstitious ignoramuses.

I dislike that most descriptions and discussions about Yetis are filtered through European experiences, and that the older reports especially have a high-handed tone that ruffles my feathers—not just racist, but classist as well. Brown people and poor people are not stupid, and what someone from one culture dismisses as a superstition may be a deeply held religious belief in another culture. Moreover, as anthropologist John Napier wrote in 1973, the superstitious sherpas that white explorers sneer at may actually have been having a sly joke at their employers’ expense—that or they’re just being polite and telling their employers what they think they want to hear. Or both, heck. People are complicated.

But consider what has happened when Europeans eager to discover the “truth” of the Yeti encounter Buddhist monks with Yeti relics. In 1959 Tom Slick, a rich Texas oilman who liked to indulge his hobby of bigfoot hunting—we met him in the giant salamander episode, you may remember—funded an expedition to Nepal to hunt for the Yeti. This was his fourth Yeti hunt, and some historians suspect he and many other explorers in the area had CIA connections. This was during the cold war, remember. But Slick’s interest in the Yeti was genuine, and during his 1958 expedition he had tried to buy a mummified Yeti hand from a Buddhist monastery in Pangboche, Nepal. The hand, along with a Yeti scalp, was a sacred relic and definitely not for sale. So in 1959 Slick arranged for explorer Peter Byrne to go back to the monastery and steal a finger from the hand. Supposedly Byrne replaced the missing finger with a human finger he had brought with him. Where on earth do you even get a human finger? Anyway, as Byrne reports, to get the finger out of Nepal he gave it to the actor Jimmy Stewart, who was one of the expedition’s backers. Stewart’s wife Gloria smuggled the Yeti finger out of the country in her lingerie case. It was later analyzed and found to be a human finger.

Everything about this story is horrible. First of all, it is not cool to steal sacred relics. Second, it’s not cool to swap out human body parts to cover your theft. And third, you know what they did with the stolen Yeti finger that turned out to be human? They lost it, that’s what they did. For decades no one knew where it had gone. Fortunately, it was rediscovered in a London museum in 2008, and DNA analysis confirmed it was human. The BBC interviewed Byrne in 2011 and his story had changed somewhat about his acquisition of the finger. He now says he paid the monastery for it. Mmhm. Sure. Someone stole the rest of the hand from the monastery in the 1990s, along with a yeti skull-cap.

Other Yeti remains have been analyzed more ethically. Sir Edmund Hillary, the guy who first summited Everest, and zoologist Marlon Perkins mounted an expedition in 1960 through ‘61, and went back to the Pangboche monastery to examine their relics. But this time, no one stole anything. In fact, the expedition paid for some repairs to the monastery, and paid for a village elder to accompany a Yeti scalp they were allowed to borrow, which they sent to be analyzed. They also raised money to construct schools and medical clinics in remote villages, among other good works.

The Yeti scalp, and others like it, turned out to be made from the shoulder skin of a goat-like wild animal called a serow. In fact, the Hillary-Perkins expedition was able to make its own Yeti scalps with serow skins dried over a conical wooden mold. It sent its homemade scalps with the borrowed scalp for analysis without telling the lab that some were not authentic. The results came back that all the scalps were made from the same type of animal skin.

In 1986 mountaineer Reinhold Messner had a terrifying encounter with an unknown animal. I’m going to quote it at length because it’s pretty awesome. It’s from his book My Quest for the Yeti, but I have taken the quote again from Abominable Science.

“Making my way through some ash-colored juniper bushes, I suddenly heard an eerie sound—a whistling noise, similar to the warning call mountain goats make. Out of the corner of my eye I saw the outline of an upright figure dart between the trees to the edge of the clearing, where low-growing thickets covered the steep slope. The figure hurried on, silent and hunched forward, disappearing behind a tree only to reappear again against the moonlight. It stopped for a moment and turned to look at me. Again I heard the whistle, more of an angry hiss, and for a heartbeat I saw eyes and teeth. The creature towered menacingly, its face a gray shadow, its body a black outline. Covered with hair, it stood upright on two short legs and had powerful arms that hung down almost to its knees. I guessed it to be over seven feet tall. Its body looked much heavier than that of a man of that size, but it moved with such agility and power toward the edge of the escarpment that I was both startled and relieved. Most I was stunned. No human would have been able to run like that in the middle of the night. It stopped again beyond the trees by the low-growing thickets, as if to catch its breath, and stood motionless in the moonlit night without looking back.”

Messner finishes the sighting by saying it rushed up the slope out of sight on all fours. Messner fled to the nearest village.

After that he spent the next ten years searching for more information on the Yeti. He examined Yeti remains in various monasteries and in all cases found they were either taxidermied creations made from various known animals, or the pelts of bears. In 1997 in the peaks of the Nanga Partains, he and his guide Rozi Ali saw what the locals called a dremo. That’s a Tibetan word commonly used for both the yeti and the Himalayan brown bear. Here’s his description:

“One afternoon, after a long trek, we encountered another dremo. He fled when he saw us, but then seemed to stop and rest in a hollow. I approached the spot from behind some ridges so that he wouldn’t pick up my scent. Rozi Ali followed me. When I began to climb down to where the animal was sleeping in the grass, Rozi Ali tried to stop me. I broke free from his grasp and came within twenty yards of the animal, where I took some good pictures. Rozi Ali, crouching some way back, begged me to make a run for it. He was sweating with fear.

“The animal woke up and looked at me in the way a startled child would a stranger. It was a young brown bear.”

He also says they saw another dremo later, while in Kashmir, and it was “running away on two legs. From a distance it looked uncannily like a wild man”. But it too was a brown bear.

Messner concluded, not unreasonably, that the Yeti was a bear. Many others agree. As it happens, I agree too, and I wonder if a bear that walks upright like a person is perhaps considered to have supernatural traits. After all, Messner found it eerie even when he knew what he was seeing. That might explain the overlap between terms for yeti and terms for bears, and would also explain why so many words translated as yeti actually mean man-bear. But I’d be delighted if a strange upright animal lives in the remote parts of the world, even if that strange animal just turns out to be a new species of bear.

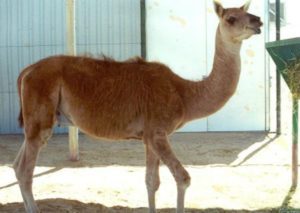

In 2014, geneticists from Oxford University analyzed hair samples from a Himalayan bear and determined that the DNA was similar to that of a 40,000 year old polar bear. But a new analysis in 2015 by geneticists from the Smithsonian and the University of Kansas was a lot less exciting, determining that the hair belonged to a native brown bear after all—but probably to a rare, endangered subspecies of brown bear that lives in parts of the Himalayas, sometimes called the Tibetan blue bear. It’s not blue, by the way. It’s brown. I don’t know why it’s called a blue bear.

The Himalayan brown bear usually lives above the timber line in the mountains and like other bears is omnivorous. That means it eats both plants and meat. It especially likes to eat marmots, a chubby rodent related to squirrels that looks a lot like a prairie dog.

Many cryptozoologists think the Yeti and other bigfoot-type creatures must be either an unknown offshoot of the human family, like a Neandertal, or another unknown great ape that has developed an upright stance, such as a descendant of Gigantopithecus. They even propose that different types of bigfoots are different species of upright ape, all unknown to science.

I do think there are a lot of unknown animals out there, but I’m definitely skeptical that somehow we’ve overlooked multiple living species of giant apes, and not only that, that we haven’t even found fossil or subfossil remains of any of them. Gigantopithecus, by the way, is RIGHT out as a possibility. It was huge, sure, and an ape, sure, but it disappeared from the fossil record 300,000 years ago and ate mostly bamboo. Some researchers think it died out due to competition with pandas, in fact. It was related to orangutans and probably looked more like a big gorilla than a human, and would not stand upright. Remember that among all mammals, humans are the only ones who have developed true bipedalism, and we’ve sacrificed a lot in exchange. For instance, we have weak backs, childbirth is much more difficult, and we frequently die from falling off our own feet and cracking our heads, despite our massively thickened skulls. Other apes would not have developed bipedalism unless they faced the same intense evolutionary pressures that our ancestors did millions of years ago. But we have found no evidence whatsoever that other apes developed bipedalism.

So what about the Yeti being the descendants of Neandertals or other close human relatives? That’s a stronger argument, but if you’ve listened to episode 25 about our close cousins, you’ll remember that they were wearing jewelry and making tools before disappearing from the fossil record only around 30,000 years ago. They didn’t have fur and wouldn’t have been walking around in the snow with bare feet. Our cousins basically looked and acted a whole lot like we do. Remember also that the ancestors of humans and our close relations have been painting our bare skins with ochre and other minerals for 300,000 years for social reasons. We’re not going to go back to sprouting thick fur coats and wandering the mountains in solitude, not without many millions of years of selective evolutionary pressures. But bears are already big hairy solitary animals, and bears can and do walk upright for stretches, especially younger animals.

I could talk about the Yeti for the next hour and still not cover all the material available, so if you’re a Yeti enthusiast who’s sputtering about me skipping all the best evidence, there are a ton of excellent podcasts who’ve covered the topic in much more detail and come up with much different conclusions than I have. I’ve included links to a bunch of them in the show notes for anyone who’s interested in digging a lot deeper into the Yeti’s history.

Next week we’ll be visiting other remote areas of the world to look at more obscure bigfoot-type legends, from Australia’s bunyip and yowie to the giants of Patagonia. Until then, remember to sample the candy you bought to give out on Halloween, to make sure you made good choices. It’s okay if you have to get more later.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast online at strangeanimalspodcast.com. We’re on Twitter at strangebeasties and have a facebook page at facebook.com/strangeanimalspodcast. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. If you like the podcast and want to help us out, leave us a rating and review on iTunes or whatever platform you listen on. We also have a Patreon if you’d like to support us that way. Rewards include stickers and twice-monthly bonus episodes.

Thanks for listening!