Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 28:39 — 29.3MB)

Subscribe: | More

It’s almost Halloween!! Our Halloween episode this year is all about some of the legends of ghostly black dogs in the UK and some other parts of the world, as well as some canid mysteries we haven’t covered before. Thanks again to Pranav for the suggestion!

This is your last chance to enter the book giveaway! You have until October 31, 2020, and that night at midnight (my time, Eastern daylight savings, or more likely when I wake up on November 1) I will randomly draw a name from all the people who have entered. To enter, just send me a message by email or Twitter or Facebook, or some other way. The contest is open to anyone in the world and if you win I’ll send you a signed copy of my books Skytown and Skyway, along with stickers and other fun stuff! I will mention that I haven’t actually received that many entries so you have a good chance of winning.

The pages I mentioned in this episode: Books I’ve Written, List of Animals, List of Cryptids, My Wishlist Page with Mailing Address

I’ve unlocked a few Patreon episodes for anyone to listen to, no login required:

The Horse-Eel

The Hook Island Sea Monster

The Minnesota Iceman

Further reading:

Shuckland

Trailing the Hounds of Hell – Black Dogs, Wish Hounds, and Other Canine Phantasms

The Lore and Legend of the Black Dog

The Mystery of North America’s Black Wolves

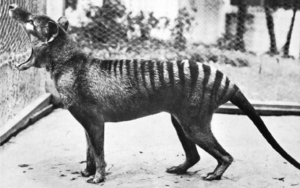

The Beast of Bungay according to the artist employed by Abraham Fleming (left) and the church door that supposedly shows burnt scratch marks from the beast’s claws (right):

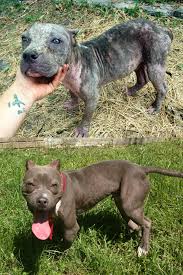

A short-eared dog AKA the ghost dog:

A Himalayan wolf:

A dhole, closest relation to the “ghost population” of extinct canids:

A black wolf (photo by Andy Skillen, and I got it from the black wolf article linked to above):

Show Transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

It’s finally Halloween, and we have an episode that’s as spooky as it gets. It’s also a little unusual, because we’re going to learn about a folklore animal called the black dog, which isn’t a real dog or a real animal. But we’ll also learn about some canid mysteries we haven’t covered before, especially some mysteries associated with wolves. This is a suggestion from Pranav, who wanted to hear about more mystery canids after episode 80.

As always before our Halloween episode, let’s take care of some housekeeping. First, I’ve unlocked some Patreon episodes for anyone to listen to. The links are in the show notes and you can click through and listen on your browser, no login required. This time we have episodes about the horse-eel, the Hook Island Sea Monster, and the Minnesota Iceman.

Next, you still have a few days left to enter the book giveaway! This is for one paperback copy each of my books Skytown and Skyway. Skytown is a fun fantasy adventure book about two young women who steal an airship and decide to become airship pirates. As you do. Skyway is about the same characters but it’s a collection of short stories, mostly set before the events of the book. The short story collection is probably about a PG rating, for parental guidance needed, while the novel is probably more PG-13, where it’s really not for people under 13 years old. To enter the giveaway, just send me a message saying you’d like to enter. At midnight on Halloween night I will draw one winner randomly and send them the books as well as stickers, bookmarks, and some other stuff, but let’s be honest, I’m probably going to forget and fall asleep, so if any entries come in overnight on Halloween I’ll add them to the list before drawing a winner on the morning of November 1. There’s a page on the website with links to the Goodreads profiles of both books if you want to take a closer look and maybe order copies, because small publishers are really hurting right now and they could use your help.

This is also a good time to remind you that there are a few other pages on the website you might want to take a look at. One has a list of animals we’ve covered on the podcast and which episodes they appear in, and another is a list of just the cryptids we’ve covered on the podcast and which episodes they appear in. The cryptids list also includes Patreon episodes, including links to unlocked episodes, so if you’re new to the show and really want more mystery animal content, you might browse through that page. There’s also a contact information page that contains a link to my book wishlist if you’re feeling generous and want to send me a book I’ve been looking for. Used books are fine, and I totally do not want anyone to spend a lot of money on me so don’t feel like you have to do this. Eventually I’ll buy them all for myself. My mailing address is on that page too and I would be delighted if you want to send me an animal drawing or a letter. I’ll write you back and send you a sticker. Oh, and if you just want a sticker, you can always email or message me and ask for one. Don’t forget to give me your mailing address.

Okay, I think that takes care of everything, so on with the spookiness! Let’s kick off this year’s Halloween episode with an account of the Beast of Bungay [pronounced Bun-gee] from Suffolk, England.

[thunder! unless I forget to add it]

On August 4, 1577, around mid-morning, a massive thunderstorm rolled through Suffolk. The Reverend Abraham Fleming wrote an account of a bizarre event that happened during the storm.

It was a Sunday and church services were underway when the storm hit. During the lightning and thunder and torrential rain, Fleming wrote that a huge black dog entered St. Mary’s Church in the small town of Bungay. It was clearly not an ordinary dog. Fleming wrote, in slightly edited modern English:

“This black dog, or the devil in such a likeness running all along down the body of the church with great swiftness, and incredible haste, among the people, in a visible form and shape, passed between two persons as they were kneeling in prayer and wrung the necks of them both at one instant clean backward, insomuch that even at a moment where they kneeled, they strangely died.”

The dog also grabbed another man, resulting in the man appearing “drawn together and shrunk up, as it were a piece of leather scorched in a hot fire: or as the mouth of a purse or bag drawn together with a string.” But that man apparently recovered. The first two died.

But that’s not all. Less than ten miles away, or 16 km, the storm advanced through the town of Blythburgh. In the Holy Trinity church the dog appeared again:

“The like thing entered, in the same shape and similitude where placing himself on a main baulk or beam whereon sometime the rood did stand, suddenly he gave a swing down through the church, and there also, as before, slew two men and a lad, and burned the hand of another person that was among the rest of the company, of whom diverse were blasted. This mischief thus wrought, he flew with wonderful force to no little fear of the assembly, out of the church in a hideous and hellish likeness.”

Fleming published his account in a pamphlet only a few weeks after the event took place, but he wasn’t a witness. He also made some mistakes. He said that the two men who died after the dog wrung their necks backwards had been kneeling in prayer, but according to the parish register, both men who died had been in the belfry during the storm. Fleming also said that the dog left burnt claw marks on the door into St. Mary’s church when it was actually the Holy Trinity church that was damaged. The church still has the same door and it’s supposed to still show the claw marks. The marks don’t look much like claw marks to me, but it’s definitely possible that they were caused by lightning.

Fleming’s account was probably heavily fictionalized to sell copies of his pamphlet, but that doesn’t stop it from being a wonderfully creepy story based on an event that did actually happen. There really was a massive storm on that date that damaged both churches and killed several people, but other contemporary accounts of the storm don’t mention a dog.

The rumor of a black dog in the storm might have started because there was an actual pet dog in the church or just outside that was frightened by the thunder and ran around in the church. Back then dogs were allowed in church but they sometimes barked or started fighting other dogs, at which point they had to be put outside. Many churches employed a man called a dog whipper to put dogs out, sometimes by using a big pair of metal tongs called dog tongs to grab a fighting dog and drag it outside. I don’t know why I find this so hilarious. Dog tongs. Like gigantic salad tongs, but for dogs.

Written accounts of ghostly black dogs go back over a thousand years in the British Isles and parts of Europe. The dogs are sometimes described as the size of a calf or even a pony, with glowing red eyes and shaggy fur. The very first black dog report anyone knows of is from France, recorded in the year 856. It occurred in a church too. A black dog with red eyes appeared in the church and ran around the altar several times before disappearing.

One well-known black dog is the Black Shuck of East Anglia, which is in eastern England and includes both Norfolk and Suffolk. The Black Shuck is a big black dog, sometimes described as having eyes as big as saucers, and in a few reports as having a single red eye in the middle of its face. The Beast of Bungay is actually considered to be part of the Black Shuck legend. Sightings of the Black Shuck still occur in Bungay, Blythburgh, and other parts of East Anglia.

For instance, this report: “Mr. John McLaughlin was working in the Autumn of 1973 for a firm that was laying new sewer lines across the marshes behind Blythburgh church. One day when he was alone, as his mate had gone into the village, he heard the sound of a dog panting very close by him, as if right by his ear, but there was no animal visible. It gave him a fright, which caused his hackles to rise, and he felt ‘uncanny.’ He was not a local man, and knew nothing of the local ‘Shuck’ legends until he was told later.”

People always like to know why something is happening, and there are lots of reasons given as to why a black dog appears. An account recorded in 1983 says that a girl was murdered on a road and after that a phantom hound had started to be seen there, while other stories say that the dog is waiting for its master, a fisherman who was lost at sea. A popular variation of this legend says that a dog drowned along with its two masters and all were found washed up on shore. Since no one knew who the people were, they were buried in separate churchyards, and the dog’s spirit travels ceaselessly between the two graves. Another legend says that a dog guarding a house was killed by wolves and that its spirit continues to guard the area. Another says the ghostly black dog guards a treasure, usually gold. But some stories just say it’s a demon or the spirit of a wicked person who died.

Here are a few more accounts, all taken from a fantastic website called Shuckland. I’ve linked to it in the show notes.

This first story is from 1968 in the town of Barnby. “George Beamish…was walking home one night and coming up to the Water Bars when he noticed a dog alongside him… He did not pay any special regard to the animal, then turned to speak to it. He looked and he saw it was no ordinary dog. It was big and black, but it had no head. He put his hand down to [touch] the animal, but it went clean through the dog…there was nothing there. He got the wind up and ran home…”

Many stories are similar, since most black dog accounts take place on a road or path. For instance, this one: “In the early years of World War Two I was stationed on an airfield at Oulton in Norfolk. Sometime in the Winter of ’41-42 I was walking along from Aylsham to Oulton Street. The night was very cold but clear. I had just passed Blickling Hall on my right when to my surprise I suddenly saw a large black dog standing in the middle of the road some few feet from me. As I called to the dog a most peculiar feeling came upon me. The nearest description I can give is that it was a ‘nervous tingling.’ I advanced towards the animal but as I went forward the animal retreated but without moving its feet, almost as though it was a cardboard ‘cut-out’ being pulled away from me with strings. The dog’s mouth was open but it made no sound. … I stopped and the dog also ceased its backward motion. After regarding me for maybe ten seconds the animal just completely disappeared. By ‘disappeared’ I mean that it did not run away but literally ‘disappeared.’ The night was very clear and I had a good view over the paddocks to my left and right. I could see no dog.”

Sometimes a witness reports that the black dog disappears through some obstacle like a wall or a closed gate: for instance, this report from Earsham [pronounced arshun] that probably occurred around 1920 to a Mrs. Wilson’s father when he was young. It was mid-December near midnight, a clear moonlit night but with snow on the ground. “As he approached the last of the first row of cottages known as Temple Bar, he said he became aware of a horrible cold tingling sensation all over, and the feeling that his hair was standing ‘on end.’ At this point, he saw a large dog, probably black, come walking through the fence of the big private house known as ‘The Elms’ on his right, cross the road in front of him, a few feet away, and disappear through the WALL of the Rectory opposite…he found there was no sign whatsoever of any footprints, or other marks on the fresh snow. At this point he panicked and ran fast as he could to my Granny’s house in the main street… At that time my father had no knowledge whatsoever of local ghosts…”

A sighting of a black dog is usually taken as a bad omen, but sometimes a black dog seems to help people. In around 1842 in Catfield in Norfolk, “[s]everal women were out one night gathering rushes, trespassing on the marshes near Catfield Hall, when they heard the keeper coming. Suddenly a large black dog appeared…and started chasing back and forth among them, whimpering. Finally one of the [women] realized it wanted them to follow it, and it led them across the worst part of the marsh to a footpath, then on to a main road and home. When they looked around for the dog, it had disappeared.”

In the early 20th century in Bawburgh [pronounced bawburr], a young man whose name is only reported as Mr. E. Ramsey “was cycling home late on a moonlit night from a darts match in Norwich. As he got near his home village he saw, sitting by the signpost, ‘the biggest hound’ that he’d ever seen, with eyes that ‘shone like coals of fire.’ Although nervous he passed the dog, but it didn’t move. Putting on speed he went on by, but half a mile further on heard him approaching from behind, ‘his paws beating the grit road.’ …[T]he dog…went by him, ‘so close [he] could smell [it].’ When it was well in front the dog stopped suddenly beside a spinney, and stood in the middle of the road facing him, looking aggressive. Mr. Ramsey stopped and dismounted in fear, looking around for someone to help him, keeping the cycle between him and the hedge. But just at that moment an unlit vehicle roared out of the spinney, ‘careering from side to side,’ and seemed to crash straight into the dog. Mr. Ramsey fell into the hedge with the cycle on top [of] him, as the vehicle rushed by so close, and away up the lane out of sight. As the witness picked himself up, he was amazed to see the dog still standing there, as he was sure it had been struck. …[T]o his surprise it just turned, and vanished into thin air. Mr. Ramsey…considered that it had saved his life on that night, since, if HE had been where the dog was, he would now be dead.”

Black dogs have many names besides Black Shuck, most of which are local terms for the local black dog. These include Hairy Jack, Shag, Skriker, Padfoot, the Yeth or Yell Hound, the Barghest, the Churchyard Beast, and Hateful Thing. These are all names from various parts of the UK, but black dogs are encountered in other places too, including parts of Europe, parts of the United States, especially in New England, and in parts of Mexico and South America. In many European mythologies, dogs symbolize death and the underworld, which may have influenced the black dog legends.

It’s certain that at least some reports of ghostly black dogs were actually encounters with ordinary dogs that happened to be black. As we talked about last week in the Dover demon episode, many animals that are active at night exhibit eyeshine as light reflects off the tapetum lucidum. This helps the animal see better in the dark. The color of a dog’s eyeshine depends on what color its eyes are but also depends on how much zinc or riboflavin is present in the pigments of its eyes, how old the dog is, and what breed it is. A dog’s eyes can shine white, green, yellow, blue, purple, orange, or red. Some dogs even have different colored eyes, so that one eye shines yellow but the other shines green, or some other combination. A big dog with a black or dark brown coat, which would look black at night, which also has orange or red eyeshine, might be mistaken for the Black Shuck when encountered on a road at night by someone who’s already familiar with the local legends.

That doesn’t explain the ghostly dogs that vanish into thin air or walk through walls, though. Don’t ask me to explain those. I love a good ghost story and I’m just going to appreciate how spooky those accounts are without worrying too much about what the black dog really is.

Let’s move on from ghostly dogs to some mystery canids. We’ll start with one that we know exists but which is probably the least well known canid in the world.

The short-eared dog lives in the Amazon rainforest and is sometimes called a ghost dog because of how shy and elusive it is. It’s the only member of its own genus. It has short legs, small, rounded ears, and a fox-like muzzle and tail. It varies in color from reddish to almost blue, but is usually brown or gray. It has partially webbed toes since it lives in wet areas. Females are considerably larger than males and instead of living in packs like many canids do, it seems to be a solitary animal. It eats small animals of various kinds, including frogs, fish, birds, crabs, and insects, and it also eats a lot of fruit. And that’s about all we know right now.

Starting in 2015, researchers placed camera traps in the southern Amazon rainforest to take pictures of mammals that lived in the area. To the team’s surprise, they kept getting photos of the short-eared dog. Some of the researchers had spent years working in the area but had never seen one of the dogs before. Many locals have never seen them either. But they kept showing up on camera.

A team of 50 scientists worked together to study the camera trap photos, and photos from other teams working in the Amazon on different projects, to determine the dog’s range and habitat, and as much other information about it as possible. Results of the study were published in May 2020 and it turns out that it’s not as rare as initially thought, although it is threatened by habitat loss, especially deforestation due to logging and development. The more we know about the short-eared dog, the more conservationists can do to protect it.

The gray wolf isn’t a mystery animal either, but there are a couple of mysteries associated with it. It lives throughout Eurasia and North America and is usually gray and white in color. There are a number of subspecies of grey wolf, but recently scientists have started taking a closer look at the genetics of some of those subspecies to determine if they might actually be separate species of wolf entirely.

That’s what has happened with the Himalayan wolf, which had long been considered to be a subspecies of grey wolf that lived in parts of the Himalaya Mountains in India. But not everyone agreed. Genetic studies of the wolf published in 2016 concluded that it isn’t all that closely related to the grey wolf, and in fact has been evolving separately from the grey wolf for 800,000 years. This year, 2020, follow-up studies have verified that the Himalayan wolf is significantly different genetically from the grey wolf. But it also turns out that the Himalayan wolf is the same animal as the Tibetan wolf, which also lives in the Himalayas. The wolves are adapted to live in high elevations, and researchers also suggest that the Tibetan mastiff, a breed of domestic dog, was developed by the ancient people of Tibet when they bred their dogs with the local wolves.

The Tibetan mastiff, by the way, is a big dog with a shaggy coat, especially a massive ruff, and is often black in color. No word on whether its eyes glow fiery red or if it can walk through walls.

The Himalayan wolf is about as closely related to the grey wolf as it is to the African golden wolf. The African golden wolf lives in northern Africa, especially in the Atlas Mountains. It’s quite small for a wolf, standing only 16 inches at the shoulder, or 40 cm. It varies in color from grey to reddish, and in fact it looks so similar to the jackals found in Africa that it used to be considered a subspecies of golden jackal. It wasn’t determined to be a wolf until 2015, when genetic analysis indicated it was more closely related to the coyote and gray wolf than it is to the golden jackal.

This is all complicated by the fact that many canids are so closely related that they can and will hybridize and produce fertile offspring. Genetic studies of the gray wolf have found that most wolves have some genetic markers of coyotes in their ancestry in the same way that many people have genetic markers of Neanderthals in our ancestry. But grey wolves also have genetic markers from another canid, one that can’t be identified.

When this happens, the unidentified ancestor is referred to as a ghost population. Many humans also have the genetics of ghost populations of hominins, by the way. One has recently been identified as the Denisovan people, but the other is still unidentified. As for the wolf’s ghost population, it’s genetically similar to a canid called the dhole. The coyote also contains genetic markers from this ghost population.

Grey wolves in North America are also more likely to exhibit melanism than other populations of wolves, which results in a wolf that is black instead of gray. Melanism isn’t uncommon in some animals. Black panthers are just melanistic leopards, for instance. Melanistic animals can hide better in low light conditions like heavy forests. But recently, a team of geneticists examined the DNA of wolves living in Yellowstone National Park to see if they could find out why so many North American wolves were melanistic compared to other populations of wolves.

They discovered that the wolves contain genetic markers of domestic dogs—but these markers are really old, not recent. The researchers estimate that this particular hybridization of grey wolves and dogs took place over 10,000 years ago in what is now Alaska. We have remains of domestic dogs from the same area, and many of them were melanistic. Researchers think ancient humans bred for the trait, and those dogs mated often enough with local wolves that melanism became much more common in the wolves too.

Why did ancient humans want black dogs? Because black dogs look really cool and spooky. Happy Halloween!

You can find Strange Animals Podcast online at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. If you like the podcast and want to help us out, leave us a rating and review on Apple Podcasts or just tell a friend. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us that way.

Thanks for listening!