Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 13:46 — 14.1MB)

Let’s learn about another mystery ape, the koolakamba (also spelled kooloo-kamba or other variations)!

Further reading:

Between the Gorilla and the Chimpanzee

The Yaounde Zoo mystery ape and the status of the kooloo-kamba

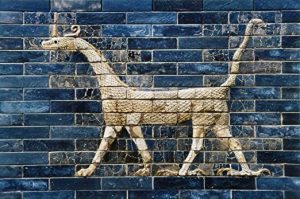

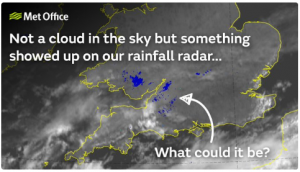

Antoine the Yaounde Zoo ape, supposedly a koolakamba:

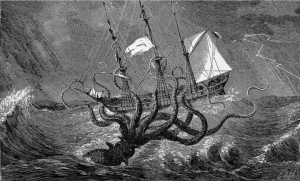

Mafuka (sometimes spelled Mafuca):

A rare photo of the Bili ape:

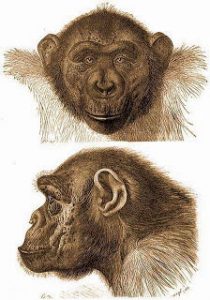

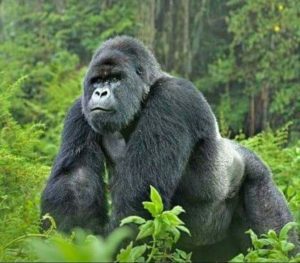

A handsome western gorilla:

A handsome western chimpanzee:

A western chimpanzee mother and baby:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

This week we’re going to round out our bonus mystery animal month with a mystery ape called the koolakamba. Every time I think we’ve covered every mystery ape out there, I find another one.

The koolakamba first appears in print in the mid-19th century, but let’s fast-forward to 1996 first and talk about a photograph of a purported koolakamba. The picture was taken at the Yaounde Zoo in Central Cameroon in Africa, and the ape was a male called Antoine. He has very black skin on his face but bright orange eyes, with a pronounced brow ridge. The picture appeared in the November 1996 issue of the Newsletter of the Internal Primate Protection League and some people suggested the ape was a hybrid of a chimpanzee and a gorilla. That’s what a koolakamba is said to be, a chimp-gorilla hybrid.

But that’s not what the koolakamba was always said to be. So let’s go back again to find out what the first European naturalists reported about this animal.

The first European to write about the koolakamba was a man called Paul DuChaillu. He was also the first European to write about several other animals, including the gorilla, and he was always eager to find more and describe them scientifically. He was the one who gave the koolakamba its name, which was supposed to be a local name for the animal, meaning “one who says ‘kooloo.’” In other words, the ape’s typical call was supposed to sound like it was saying kooloo. I’ve chosen the spelling koolakamba for this episode, as you’ll see in the show notes, but I’ve also seen it as kooloo-kamba with various spellings.

Chimpanzees and gorillas were well known to the local people, of course, but although they weren’t quote-unquote discovered until much later, early travelers to Africa mentioned them occasionally. The first mention of both dates to about 1600. In 1773 a British merchant wrote about three apes he heard about from locals: the chimpanzee, the gorilla, and a third ape called the itsena.

DuChaillu thought the koolakamba was a separate species too, one that looked similar to both the gorilla and the chimpanzee. Other explorers, big game hunters, and zoologists thought it was a chimp-gorilla hybrid, which accounted for its similarity to both apes. A few thought the koolakamba was just a subspecies of chimp, while a few thought it was a subspecies of gorilla.

The argument of what precisely the koolakamba was is still ongoing, but no one ever denied that the koolakamba existed. After all, there were specimens, both dead and alive. In July 1873, a female chimpanzee named Mafuka was shipped to the Dresden Zoo, and she was supposed to be a koolakamba.

We have some beautifully done engravings of her face that are so detailed they might as well be photographs. Mafuka had black skin on her face, pronounced brow ridges, fairly small ears, and a gorilla-like nose. Her hair was black with a reddish tinge. She was also a big ape although she was young, measuring almost four feet high, or 120 cm. She only lived two and a half years in captivity, unfortunately, dying in December of 1875.

Some zoologists classified Mafuka as a young gorilla, while others thought she was a chimpanzee. Others thought she was a hybrid of the two apes. In 1899 an anatomist claimed she was a koolakamba and a different species from either ape.

Other koolakamba apes have been identified after Mafuka, including one called Johanna kept by Barnum & Bailey at the end of the 19th century. But there are more recent examples. A chimpanzee colony kept at the Holloman Air Force Base in New Mexico supposedly had a koolakamba in the 1960s. An ape expert named Osman Hill studied the chimps at Holloman and published his observations in the late 1960s in a comprehensive taxonomy of the chimpanzee. Hill was convinced that the koolakamba was a subspecies of chimp, which he named Pan troglodytes kooloo-kamba.

But Hill’s description of the koolakamba varies from DuChaillu’s description. Basically the only agreements between the two is that the koolakamba has a black face—dark enough that it’s usually referred to as ebony—and pronounced brow ridges.

And that’s the trouble. No one seems able to agree on what the koolakamba actually definitively looks like. Part of the problem is that Europeans who went to Africa to kill animals and claim them as new to science asked the locals what a particular animal was, and assumed that the locals thought about animal relationships the same way Europeans do. That is, we think of animals as distinct species even if they look similar. But many people in Africa, especially hunters, and especially in the 19th century and earlier, approached animals with a different mindset. They needed to know what animals were good to eat, what animals were safe to hunt and which were dangerous and should be avoided, and so forth. Often, they gave different names to the same species of animal based on physical characteristics like size or color. But the Europeans didn’t know this. Many of the local names reported for apes that resemble what we might call the koolakamba translate to things like “gorilla’s brother” and “gorilla-like.”

So there are a lot of things going on here. Let’s see if we can make some sense out of this confusion.

The first big question, of course, is if chimpanzees and gorillas even live in the same parts of Africa. And it turns out they do, at least in a few places in western Africa. Where the territories of chimps and gorillas overlap, they generally avoid each other. It’s rare that they interact at all, and extremely rare that they get in fights. Even if they were feeding in the same small area, they wouldn’t need to fight because they eat different things. Gorillas mostly eat leaves and twigs, while chimps prefer fruit and meat. Also, of course, gorillas stay on the ground while chimps spend most of their time in trees.

So there is enough population overlap that there’s a potential for gorillas and chimpanzees to interact. That doesn’t mean they hybridize, of course. While gorillas and chimpanzees do share a subfamily, they don’t share a genus, which means they’re not very closely related. Chimps are actually more closely related to humans than to gorillas, and we share the same subfamily with both. If you listened to episode 120 about hybrid animals, you may remember that the less closely related two species of animal are, the less likely they are to be interested in mating, the less likely that a pregnancy will result even if they do mate, and the less likely that the baby will survive even if the female does get pregnant. So while it’s extremely unlikely that gorillas and chimps could or would hybridize, it’s not completely out of the question. But even if it does happen, it would be an extremely rare occurrence for a chimp-gorilla hybrid to be born at all, much less live to adulthood.

So we can make a check-mark next to the “hybrid ape” hypothesis, but only a very small check-mark.

Could the koolakamba be a separate species of ape entirely, something new to science? That wouldn’t explain why it’s generally seen in the company of chimpanzees that look like ordinary chimps, not other koolakambas. There are reports that the koolakamba is solitary or only hangs out on the edges of chimp societies, but I can’t find any good sources for these claims and they may not be accurate. If it is a rare species of ape related to the chimpanzee, it shouldn’t be hanging out with chimps. Different species with the same dietary and environmental needs don’t live in the same place. One will always outcompete the other, either driving it to extinction or into another area.

So I’d say no check-mark next to the new species of ape hypothesis.

If you remember episode 102 where we talked about the Bili ape, it turned out that the Bili ape is a population of chimps where the males grow especially large and look gorilla-like. Could the koolakamba actually be the same thing as a Bili ape? The Bili ape is only found in far northern Congo in the Bili Forest, which is close to central Africa, while the koolakamba is only reported from West Africa. So no check-mark for this hypothesis either, although that was a good suggestion.

Chimps can show a lot of variety in facial features, including skin color and ear shape and size, and so on. They also vary in overall body size, just as any animal does. I suspect the main reason that the koolakamba is so often considered a gorilla-chimpanzee hybrid is because the koolakamba’s face is always described as ebony or jet black. This is uncommon in chimps, but all gorillas have dark gray or black skin.

Some populations of the subspecies of chimp that lives in West Africa, the western chimpanzee, are so different from other chimps that some researchers suggest it may be a different species. These populations use spears to hunt, cool off by swimming and playing in water, are more social between tribes than other chimps, and even sometimes live in caves. They also typically live in savannas or open woodland instead of thick forest. Until recently, most observational studies of chimps in the wild have focused on the eastern chimpanzee, so researchers were shocked to learn how different the western chimp is. And the western chimpanzee is generally a little larger than eastern chimps.

It may be the case that the koolakamba isn’t a separate type of animal but a western chimpanzee that shows individual differences that seem striking to us. The fact that even ape experts and local hunters can’t agree on what the koolakamba actually looks like suggests that it’s not a separate subspecies or even a hybrid. It’s just a chimp that happens to have some facial features that look slightly more gorilla-like than other chimps. This is where I would put a nice big check-mark, pending new information.

For all we know, chimps think other chimps with koolakamba-type features are absolutely gorgeous. Or other chimps might think they look a little too gorilla-like, so they might be considered kind of ugly.

I like to imagine a mother chimp looking at her newborn baby and thinking, “Oh my gosh, what a beauty! Look at those distinguished brow ridges and attractive nose. My little baby is going to be the star of the whole troop one day!” But then again, all mothers think that about their babies.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast online at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. If you like the podcast and want to help us out, leave a rating and review on Apple Podcasts or wherever you listen to podcasts. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us that way.

Thanks for listening!