Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 9:43 — 10.8MB)

Thanks to Cara for suggesting we talk about the long-beaked echidna this week!

Further reading:

Found at last: bizarre, egg-laying mammal finally rediscovered after 60 years

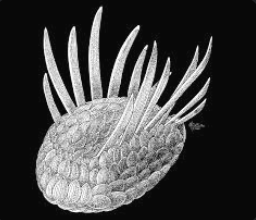

A short-beaked echidna:

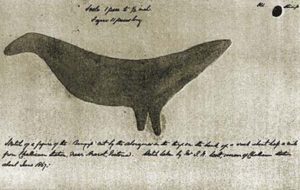

The rediscovered Attenborough’s long-beaked echidna:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

This week we’re going to learn about an animal suggested by Cara, the echidna, also called the spiny anteater. It’s a type of mammal, but it’s very different from almost all the mammals alive today. We talked about the echidna briefly in episode 45, but this week we’re going to learn more about it, especially one that was thought to be extinct but was recently rediscovered.

Cara specifically suggested we learn about the long-beaked echidna, which lives only in New Guinea. The short-beaked echidna lives in New Guinea and Australia. The names short and long beaked make it sound like the echidna is a bird, but the beak is actually just a snout. It just looks beak-like from a distance and is covered with tough skin, sort of like the platypus’s snout is sometimes called a duck-bill.

In June and July of 2023, an expedition made up of scientists and local experts from various parts of Indonesia, as well as from the University of Oxford in England, discovered and rediscovered a lot of small animals in the Cyclops Mountains. They even discovered an entire cave system that no one but some local people had known about, and they discovered it when one of the expedition members stepped on a mossy spot in the forest and fell straight through down into the cave. But one animal they were really hoping to see hadn’t made an appearance and they worried it was actually extinct. That one was Attenborough’s long-beaked echidna, a type of mammal known as a monotreme.

There are three big groups of mammals. The biggest is the placental mammal group, which includes humans, dogs, cats, mice, bats, horses, whales, giraffes, and so on. A female placental mammal grows her babies inside her body in the uterus, each baby wrapped in a fluid-filled sac called a placenta. Placental mammals are pretty well developed when they’re born.

The second type is the marsupial mammal group, which includes possums, kangaroos, koalas, wombats, sugar gliders, and so on. A female marsupial has two uteruses, and while her babies initially grow inside her, they’re born very early. A baby marsupial, called a joey, is just a little pink squidge about the size of a bean that’s not anywhere near done growing, but it’s not completely helpless. It has relatively well developed front legs so it can crawl up its mother’s fur and find a teat. Some species of marsupial have a pouch around its teats, like possums and kangaroos, but other species don’t. Once the baby finds a teat, it clamps on and stays there for weeks or months while it continues to grow.

The third and rarest type of mammal these days is the monotreme group, and monotremes lay eggs. But their eggs aren’t like bird eggs, they’re more like reptile eggs, with a soft, leathery shell. The female monotreme keeps her eggs inside her body until it’s almost time for them to hatch. The babies are small squidge beans like marsupial newborns, and I’m delighted to report that they’re called puggles. There are only two monotremes left alive in the world today, the platypus and the echidna. The echidna has a pouch and after a mother echidna lays her single egg, she tucks it in the pouch.

Monotremes show a number of physical traits that are considered primitive. Some of the traits, like the bones that make up their shoulders and the placement of their legs, are shared with reptiles but not found in most modern mammals. Other traits are shared with birds. The word monotreme means “one opening,” and that opening, called a cloaca, is used for reproductive and excretory systems instead of those systems using separate openings.

It wasn’t until 1824 that scientists figured out that monotreme moms produce milk. They don’t have teats, so the puggles lick the milk up from what are known as milk patches. Before then a lot of scientists argued that monotremes weren’t mammals at all and should either be classified with the reptiles or as their own class, the prototheria.

It’s easy to think, “Oh, that mammal is so primitive, it must not have evolved much since the common ancestor of mammals, birds, and reptiles was alive 315 million years ago,” but of course that’s not the case. It’s just that the monotremes that survived did just fine with the basic structures they evolved a long time ago. There were no evolutionary pressures to develop different shoulder bones or stop laying eggs. Other structures have evolved considerably.

Monotremes aren’t closely related to any of the other mammals alive today, either marsupial or placental mammals. The last shared ancestor lived at least 163 million years ago and possibly much earlier, maybe even 220 million years ago. The first dinosaurs lived around 230 million years ago, so we are talking a very long time ago.

The echidna is relatively closely related to the platypus and its ancestors probably looked and acted a lot like a platypus, including being largely aquatic. The echidna is adapted to life on land, even though it can swim quite well. It looks superficially like a big hedgehog since it’s covered in spines as well as hair, and if it feels threatened it will curl up into a ball like a hedgehog with its spines sticking out. It’s also a strong digger and will often dig a shallow hole very quickly when threatened, so that a potential predator encounters basically a bunch of spines sticking up out of the dirt. But unlike a hedgehog, which is usually small enough to fit in an adult human’s hand, the echidna can grow over 20 inches long, or 52 cm, and a big male can weigh as much as 13 lbs, or 6 kg.

The echidna has a long, skinny snout with a pair of nostrils at the end. The snout is bare of fur and the echidna pokes it into the ground and leaf litter to find the worms and other small invertebrates it eats. Not only does it have a good sense of smell to locate food, its snout also contains electroreceptors that allow it to sense the tiny muscle movements of its prey. The short-beaked echidna mostly eats termites and ants, while the long-beaked echidna mostly eats earthworms. The echidna doesn’t have teeth and its mouth is tiny, but it has a long sticky tongue to lick up the animals it eats. The long-beaked echidna’s tongue has tiny spines on it, sort of like a cat’s tongue has tiny spines that help it groom its fur, but the spines on the echidna’s tongue help it stab worms and insect larvae and drag them into its mouth.

Attenborough’s long-beaked echidna is a subspecies that was only discovered by scientists in 1961. It’s only known from a single specimen, and it hadn’t been seen since. In 2007 a scientific expedition found signs that an echidna was still living in the Cyclops Mountains, namely nose-pokes in the dirt where an echidna had been looking for food, but despite lots of searching for the animal, no one had seen it. Since the echidna is nocturnal and spends most of the day sleeping in its burrow, it’s hard to spot even under the best conditions.

The 2023 expedition used over 80 trail cameras to try and find the echidna. The trail cams were set up for four weeks and not a single one recorded a single echidna—until the very last day, and even then it was almost the very last video on the memory card. It’s just a short little video of an echidna just walking along on its way to do echidna stuff, but it made a big difference for the scientists.

Now that we know that Attenborough’s long-beaked echidna isn’t extinct, scientists can work with local people to help protect it and its habitat.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us for as little as one dollar a month and get monthly bonus episodes.

Thanks for listening!