Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 19:50 — 23.3MB)

Subscribe: | More

This week we have our annual updates and corrections episode, and at the end of the episode we’ll learn about a really weird clam I didn’t even think was real at first.

Thanks to Simon and Anbo for sending in some corrections!

Further reading:

Lessons on transparency from the glass frog

Hidden, never-before-seen penguin colony spotted from space

Rare wild asses spotted near China-Mongolia border

Aye-Ayes Use Their Elongated Fingers to Pick Their Nose

Homo sapiens likely arose from multiple closely related populations

Scientists Find Earliest Evidence of Hominins Cooking with Fire

153,000-Year-Old Homo sapiens Footprint Discovered in South Africa

Newly-Discovered Tyrannosaur Species Fills Gap in Lineage Leading to Tyrannosaurus rex

Earth’s First Vertebrate Superpredator Was Shorter and Stouter than Previously Thought

252-Million-Year-Old Insect-Damaged Leaves Reveal First Fossil Evidence of Foliar Nyctinasty

The other paleo diet: Rare discovery of dinosaur remains preserved with its last meal

The Mongolian wild ass:

The giant barb fish [photo from this site]:

Enigmonia aenigmatica, AKA the mangrove jingle shell, on a leaf:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

This week is our annual updates and corrections episode, but we’ll also learn about the mangrove jingle shell, a clam that lives in TREES. A quick reminder that this isn’t a comprehensive updates episode, because that would take 100 years to prepare and would be hours and hours long, and I don’t have that kind of time. It’s just whatever caught my eye during the last year that I thought was interesting.

First, we have a few corrections. Anbo emailed me recently with a correction from episode 158. No one else caught this, as far as I can remember. In that episode I said that geckos don’t have eyelids, and for the most part that’s true. But there’s one family of geckos that does have eyelids, Eublepharidae. This includes the leopard gecko, and that lines up with Anbo’s report of having a pet leopard gecko who definitely blinked its eyes. This family of geckos are sometimes even called eyelid geckos. Also, Anbo, I apologize for mispronouncing your name in last week’s episode about shrimp.

After episode 307, about the coquí and glass frogs, Simon pointed out that Hawaii doesn’t actually have any native frogs or amphibians at all. It doesn’t even have any native reptiles unless you count sea snakes and sea turtles. The coqui frog is an invasive species introduced by humans, and because it has no natural predators in Hawaii it has disrupted the native ecosystem in many places, eating all the available insects. Three of the Hawaiian islands remain free of the frogs, and conservationists are working to keep it that way while also figuring out ways to get them off of the other islands. Simon also sent me the chapter of the book he’s working on that talks about island frogs, and I hope the book is published soon because it is so much fun to read!

Speaking of frogs, one week after episode 307, an article about yet another way the glass frog is able to hide from predators was published in Science. When a glass frog is active, its blood is normal, but when it settles down to sleep, the red blood cells in its blood collect in its liver. The liver is covered with teensy guanine crystals that scatter light, which hides the red color from view. That makes the frog look even more green and leaf-like!

We’ve talked about penguins in several episodes, and emperor penguins specifically in episode 78. The emperor penguin lives in Antarctica and is threatened by climate change as the earth’s climate warms and more and more ice melts. We actually don’t know all that much about the emperor penguin because it lives in a part of the world that’s difficult for humans to explore. In December 2022, a geologist named Peter Fretwell was studying satellite photos of Antarctica to measure the loss of sea ice when he noticed something strange. Some of the ice had brown stains.

Dr Fretwell knew exactly what those stains were: emperor penguin poop. When he obtained higher-resolution photos, he was able to zoom in and see the emperor penguins themselves. But this wasn’t a colony he knew about. It was a completely undiscovered colony.

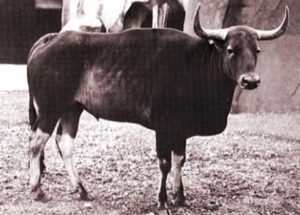

In episode 292 we talked about a mystery animal called the kunga, and in that episode we also talked a lot about domestic and wild donkeys. We didn’t cover the Mongolian wild ass in that one, but it’s very similar to wild asses in other parts of the world. It’s also called the Mongolian khulan. It used to be a lot more widespread than it is now, but these days it only lives in southern Mongolia and northern China. It’s increasingly threatened by habitat loss, climate change, and poaching, even though it’s a protected animal in both Mongolia and China.

In February of 2023, a small herd of eight Mongolian wild asses were spotted along the border of both countries, in a nature reserve. A local herdsman noticed them first and put hay out to make sure the donkeys had enough to eat. The nature reserve has a water station for wild animals to drink from, and has better grazing these days after grassland ecology measures were put into place several years ago.

In episode 233 we talked about the aye-aye of Madagascar, which has weird elongated fingers. Its middle finger is even longer and much thinner than the others, which it uses to pull invertebrates from under tree bark and other tiny crevices. Well, in October of 2022 researchers studying aye-ayes started documenting another use for this long thin finger. The aye-ayes used it to pick their noses. It wasn’t just one aye-aye that wasn’t taught good manners, it was widespread. And I hope you’re not snacking while I tell you this, the aye-aye would then lick its finger clean. Yeah. But the weirdest thing is that the aye-aye’s thin finger is so long that it can potentially reach right through the nose right down into the aye-aye’s throat.

It’s pretty funny and gross, but wondering why some animals pick their noses is a valid scientific question. A lot of apes and monkeys pick their noses, as do humans (not that we admit it most of the time), and now we know aye-ayes do too. The aye-aye is a type of lemur and therefore a primate, but it’s not very closely related to apes and monkeys. Is this just a primate habit or is it only seen in primates because we have fingers that fit into our nostrils? Would all mammals pick their nose if they had fingers that would fit up in there? Sometimes if you have a dried snot stuck in your nose, it’s uncomfortable, but picking your nose can also spread germs if your fingers are dirty. So it’s still a mystery why the aye-aye does it.

A recent article in Nature suggests that Homo sapiens, our own species, may have evolved not from a single species of early human but from the hybridization of several early human species. We already know that humans interbred with Neandertals and Denisovans, but we’re talking about hybridization that happened long before that between hominin species that were even more closely related.

The most genetically diverse population of humans alive today are the Nama people who live in southern Africa, and the reason they’re so genetically diverse is that their ancestors have lived in that part of Africa since humans evolved. Populations that migrated away from the area, whether to different parts of Africa or other parts of the world, had a smaller gene pool to draw from as they moved farther and farther away from where most humans lived.

Now, a new genetic study of modern Nama people has looked at changes in DNA that indicate the ancestry of all humans. The results suggest that before about 120,000 to 135,000 years ago, there was more than one species of human, but that they were all extremely closely related. Since these were all humans, even though they were ancient humans and slightly different genetically, it’s probable that the different groups traded with each other or hunted together, and undoubtedly people from different groups fell in love just the way people do today. Over the generations, all this interbreeding resulted in one genetically stable population of Homo sapiens that has led to modern humans that you see everywhere today. To be clear, as I always point out, no matter where people live or what they look like, all people alive today are genetically human, with only minor variations in our genetic makeup. It’s just that the Nama people still retain a lot of clues about our very distant ancestry that other populations no longer show.

To remind everyone how awesome out distant ancestors were, here’s one new finding of how ancient humans lived. We know that early humans and Neandertals were cooking their food at least 170,000 years ago, but recently archaeologists found the remains of an early hominin settlement in what is now Israel where people were cooking fish 780,000 years ago. There were different species of fish remains found along with the remains of cooking fires, and some of the fish are ones that have since gone extinct. One was a carp-like fish called the giant barb that could grow 10 feet long, or 3 meters.

In other ancient human news, the oldest human footprint was discovered recently in South Africa. You’d think that we would have lots of ancient human footprints, but that’s actually not the case when it comes to footprints more than 50,000 years old. There are only 14 human footprints older than that, although there are older footprints found made by ancestors of modern humans. The newly discovered footprint dates to 153,000 years ago.

It wouldn’t be an updates episode without mentioning Tyrannosaurus rex. In late 2022 a newly discovered tyrannosaurid was described. It lived about 76 million years ago in what is now Montana in the United States, and while it wasn’t as big as T. rex, it was still plenty big. It probably stood about seven feet high at the hip, or a little over 2 meters, and might have been 30 feet long, or 9 meters. It probably wasn’t a direct ancestor of T. rex, just a closely related cousin, although we don’t know for sure yet. It’s called Daspletosaurus wilsoni and it shows some traits that are found in older Tyrannosaur relations but some that were more modern at the time.

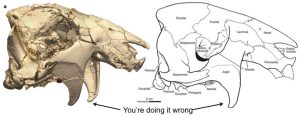

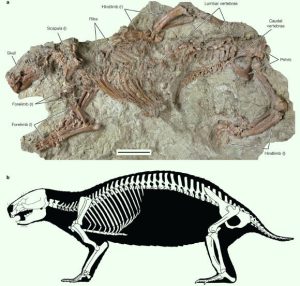

Dunkleosteus is one of a number of huge armored fish that lived in the Devonian period, about 360 million years ago. We talked about it way back in episode 33, back in 2017, and at that time paleontologists thought Dunkleosteus terrelli might have grown over 30 feet long, or 9 meters. It had a heavily armored head but its skeleton was made of cartilage like a shark’s, and cartilage doesn’t generally fossilize, so while we have well-preserved head plates, we don’t know much about the rest of its body.

With the publication in early 2023 of a new study about dunkleosteus’s size, we’re pretty sure that 30 feet was a huge overestimation. It was probably less than half that length, maybe up to 13 feet long, or almost 4 meters. Previous size estimates used sharks as size models, but dunkleosteus would have been shaped more like a tuna. Maybe you think of tuna as a fish that makes a yummy sandwich, but tuna are actually huge and powerful predators that can grow up to 10 feet long, or 3 meters. Tuna are also much heavier and bigger around than sharks, and that was probably true for dunkleosteus too. The study’s lead even says dunkleosteus was built like a wrecking ball, and points out that it was probably the biggest animal alive at the time. I’m also happy to report that people have started calling it chunk-a-dunk.

We talked about trace fossils in episode 103. Scientists can learn a lot from trace fossils, which is a broad term that encompasses things like footprints, burrows, poops, and even toothmarks. Recently a new study looked at insect damage on leaves dating back 252 million years and learned something really interesting. Some modern plants fold up their leaves at night, called foliar nyctinasty, which is sometimes referred to as sleeping. The plant isn’t asleep in the same way that an animal falls asleep, but “sleeping” is a lot easier to say than foliar nyctinasty. Researchers didn’t know if folding leaves at night was a modern trait or if it’s been around for a long time in some plants. Lots of fossilized leaves are folded over, but we can’t tell if that happened after the leaf fell off its plant or after the plant died.

Then a team of paleontologists from China and Sweden studying insect damage to leaves noticed that some leaves had identical damage on both sides, exactly as though the leaf had been folded and an insect had eaten right through it. That’s something that happens in modern plants when they’re asleep and the leaves are folded closed.

The team looked at fossilized leaves from a group of trees called gigantopterids, which lived between 300 and 250 million years ago. They’re extinct now but were advanced plants at the time, some of the earliest flowering plants. They also happen to have really big leaves that often show insect damage. The team determined that the trees probably did fold their leaves while sleeping.

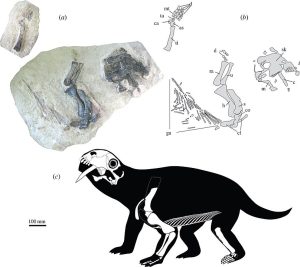

In episode 151 we talked about fossils found with other fossils inside them. Basically it’s when a fossil is so well preserved that the contents of the dead animal’s digestive system are preserved. This is incredibly rare, naturally, but recently a new one was discovered.

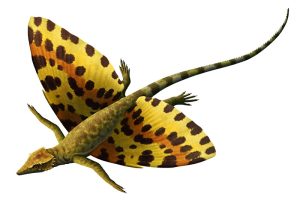

Microraptor was a dinosaur that was only about the size of a modern crow, one of the smallest dinosaurs, and it probably looked a lot like a weird bird. It could fly, although probably not very well compared to modern birds, and in addition to front legs that were modified to form wings, its back legs also had long feathers to form a second set of wings.

Several exceptionally well preserved Microraptor fossils have been discovered in China, some of them with parts of their last meals in the stomach area, including a fish, a bird, and a lizard, so we knew they were generalist predators when it came to what they would eat. Now we have another Microraptor fossil with the fossilized foot of a mammal in the place where the dinosaur’s stomach once was. So we know that Microraptor ate mammals as well as anything else it could catch, although we don’t know what kind of mammal this particular leg belonged to. It may be a new species.

Let’s finish with the mangrove jingle shell. I’ve had it on the list for a long time with a lot of question marks after it. It’s a clam that lives in trees, and I actually thought it might be an animal made up for an April fool’s joke. But no, it’s a real clam that really does live in trees.

The mangrove jingle shell lives on the mangrove tree. Mangroves are adapted to live in brackish water, meaning a mixture of fresh and salt water, or even fully salt water. They mostly live in tropical or subtropical climates along coasts, and especially like to live in waterways where there’s a tide. The tide brings freshly oxygenated water to its roots. A mangrove tree needs oxygen to survive just like animals do, but it has trouble getting enough through its roots when they’re underwater. Its root system is extensive and complicated, with special types of roots that help it stay upright when the tide goes out and special roots called pneumatophores, which stick up above the water or soil and act as straws, allowing the tree to absorb plenty of oxygen from the air even when the rest of the root system is underwater. These pneumatophores are sometimes called knees, but different species of mangrove have different pneumatophore shapes and sizes.

One interesting thing about the mangrove tree is that its seeds actually sprout while they’re still attached to the parent tree. When it’s big enough, the seedling drops off its tree into the water and can float around for a long time before it finds somewhere to root. If can even survive drying out for a year or more.

The mangrove jingle shell clam lives in tropical areas of the Indo-Pacific Ocean, and is found throughout much of coastal southeast Asia all the way down to parts of Australia. It grows a little over one inch long, or 3 cm, and like other clams it finds a place to anchor itself so that water flows past it all the time and it can filter tiny food particles from the water. It especially likes intertidal areas, which happens to be the same area that mangroves especially like.

Larval jingle shells can swim, but they need to find somewhere solid to anchor themselves as they mature. When a larva finds a mangrove root, it attaches itself and grows a domed shell. If it finds a mangrove leaf, since mangrove branches often trail into the water, it attaches itself to the underside and grows a flatter shell. Clams attached to leaves are lighter in color than clams attached to roots or branches. Fortunately, the mangrove is an evergreen tree that doesn’t drop its leaves every year.

So there you have it. Arboreal clams! Not a hoax or an April fool’s joke.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. If you like the podcast and want to help us out, leave us a rating and review on Apple Podcasts or Podchaser, or just tell a friend. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us for as little as one dollar a month and get monthly bonus episodes.

Thanks for listening!