Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 9:24 — 9.7MB)

This week’s almost late but NOT LATE OKAY episode is about the Chinese ink monkey!

A pygmy tarsier, probably not an ink monkey:

Further reading:

The Search for the Last Undiscovered Animals by Karl P.N. Shuker

Further listening:

Relic: The Lost Treasure Podcast – I’m a guest in episode 15 but all the episodes are great!

Bonus episode since this one is so short (click through and hit play)

Episode transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

This week’s episode was supposed to be about animals that were saved from extinction by human intervention, but between National Novel Writing Month, the Thanksgiving holidays, and the release of Animal Crossing: Pocket Camp I didn’t get the research completed. So that episode will run in a week or two and we’ll learn about something else this week. Something short, because it’s Sunday and I need to get this episode edited and uploaded so you can listen to it first thing Monday morning.

But first, I want to tell you about an awesome podcast who had me as a guest last week. If you don’t already listen to Relic: The Lost Treasure podcast, I highly recommend it. It’s family friendly and a great take on an aspect of history that doesn’t always get the in-depth research it deserves. In between regular seasons, the host, Maxwell, releases roundtable discussion episodes with different people to cover topics that maybe aren’t exactly about lost treasure, but close. I appeared in episode 15, called “Back from Extinction,” where we discussed animals that were declared extinct but have been rediscovered, although not without controversy. I’ll put a link in the show notes so you can go check that one out. I’d planned my own saved from extinction episode as a sort of follow-up, but time got away from me.

So what are we talking about today? In honor of the end of National Novel Writing Month, which is kicking my butt this year, we’re investigating a mystery animal called the Chinese Ink Monkey.

The story goes that in antiquity, as far back as 2,000 BCE, a tiny primate known as an ink monkey was frequently the pet of scholars and scribes in China. It wasn’t just a cute little pet, it was useful. It was intelligent and could be trained to prepare ink, which back in those days came in blocks and had to be ground into powder and mixed with water to the right consistency. It would turn book pages so the scholar could read hands-free, it would hand pens and other items to the scholar, and it was small enough to sleep in the scholar’s brush pot or desk drawer. Such a useful little creature was highly sought after, but was supposed to have gone extinct at some point centuries ago.

According to a book of Chinese lore called The Dragon Book, published in English in 1938, the ink monkey was only around 5 inches long, or 13 cm. Its sleek fur was black and soft and it had red eyes. It was also supposed to drink any ink remaining at the end of the day as its preferred food.

Since ink in those days was frequently made with precious materials like sandalwood, crushed pearls, musk, rare herbs, and even gold, and those things are not just valuable, they’re not all that nutritious, ink monkeys probably didn’t actually drink ink. But was it even a real animal or just a legend?

In April of 1996, the ink monkey story got media attention when a press release from the official New China News Agency announced its rediscovery in the Wuyi Mountains of Fujian Province. The press release didn’t have many details at all. It basically just reported that the animal was mouse-sized and had been found.

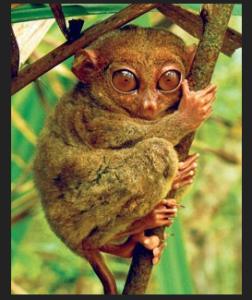

The smallest monkey alive today is the pygmy marmoset from South America, which is about 10 inches long, or almost 26 cm. But there is another animal that looks like a monkey but which is no more than about six inches long, or 15 cm, not counting its tail.

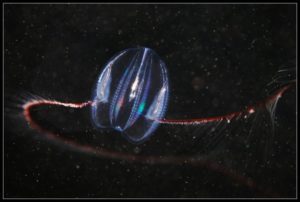

The tarsier is a nocturnal primate with huge round eyes, mouse-like ears, and sucker-like discs at the ends of its toes which it uses to climb trees. Its tail is extremely long, as are its hind legs, which helps it jump through the trees where it spends almost its whole life. While the various species of tarsier are only found on various islands of Southeast Asia today, they were once more widespread. One extinct species did live in China, but not recently. Not even remotely recently. More like 35 to 40 million years ago.

The smallest species is the pygmy tarsier, which is only found in central Sulawesi in Indonesia. It was thought extinct for decades until 2000, when it was rediscovered by local scientists. It’s only about four inches long, or 10.5 cm.

There’s still some controversy as to whether the tarsier is actually a primate. DNA studies haven’t cleared it up yet. But one thing is clear: the tarsier is a heckin adorable little guy. Its eyes are each as big as its brain and most pictures of tarsiers taken in daylight show it squinting as though it’s considering an important philosophical question. The tarsier’s fur is soft, usually beige or orangey in color, and its eyes are golden.

We’ve met the tarsier before briefly in episode eight, the strange recordings episode, because the tarsier communicates in infrasound—sounds too high for humans to hear. It’s carnivorous too, mostly eating insects but it will also eat birds, bats, and reptiles when it can catch them.

But back to the press release that the ink monkey had been rediscovered in China. At least one imminent naturalist, Sir David Attenborough himself, suggested that a species of tarsier might easily have been living in China all along without being known to science. While it is doubtful that a tarsier could learn to prepare ink or turn book pages, it’s also possible that if a famous scholar kept one as a pet, the story of its helpfulness might have been added over the centuries.

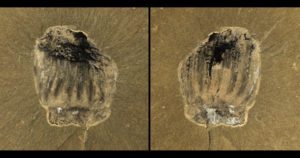

The mystery of the ink monkey’s rediscovery was cleared up by zoologist Karl Shuker, who is basically the expert on the ink monkey. Most of my research for this episode comes from his book The Search for the Last Undiscovered Animals. I’ll put a link in the show notes, of course. He discovered that a few weeks before the official press release, a short account of a discovery was published in the London Times on April 5, 1996. That report was about the discovery of a mouse-sized primate in China, sure, but not a living animal. This was a fossil discovery—specifically, a fossil jaw of an tiny proto-monkey that lived around 43 million years ago.

As Shuker concludes, the confusion probably stems from a poor English translation in the press release, leading to reporters thinking a live animal had been discovered.

But that doesn’t mean there wasn’t once a real primate that gave rise to the Chinese ink monkey legend—whether it’s a tarsier or an actual monkey or something else Maybe one day we’ll find out.

That’s it for this episode. I warned you it would be short. To make it up to you, I’ll unlock another Patreon episode for anyone to listen to, this one about mammoths and mastodons. That one probably should have been a regular episode anyway. I’ll put a link directly to the episode in the show notes and you don’t need a Patreon login to listen to it, just click the link and press play.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast online at strangeanimalspodcast.com. We’re on Twitter at strangebeasties and have a facebook page at facebook.com/strangeanimalspodcast. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. If you like the podcast and want to help us out, leave us a rating and review on iTunes or whatever platform you listen on. We also have a Patreon if you’d like to support us that way.

Thanks for listening!