Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 20:55 — 16.5MB)

Subscribe: | More

I’ve been meaning to do a big cat episode for a while, thanks to listener Damian who suggested lions and tigers! But when I started my research, I immediately got distracted by all the reports of mysterious big cats. So here’s another mysteries episode!

Here are the links to some Patreon episodes that I’ve unlocked for anyone to listen to. Just click on the link and a page will open, and you can listen on the page. No need to log in.

Marsupial lions

Blue tigers and black lions

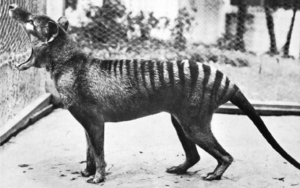

The Queensland tiger, which is not actually about any kind of actual tiger

A lion and cub. This picture made me die:

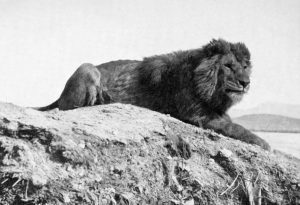

The Barbary lion, possibly extinct, possibly not:

Watch out! Tigers!

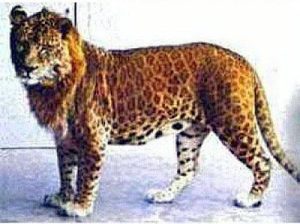

A king leopard with stripe-like markings instead of spots:

Further reading:

Hybrid and Mutant big cats

Peruvian mystery jaguar skulls studied

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

This week we’re going to learn about some mystery big cats. We’ve touched on big cats before in various episodes, including the British Big Cats phenomenon in episode 52. We’re definitely going to see some more out of place animals this week, along with lots of information about big cats of various kinds. Thanks to Damian who requested an episode about lions and tigers ages ago.

I’ve also unlocked three Patreon episodes so that anyone can listen to them. They won’t show up in your feed, but there are links in the show notes and you can click through and listen on your browser without needing a patreon login. The first is about marsupial lions and the second is about blue tigers and other big cats with anomalous coat colors. The sound quality on the blue tigers episode is not that great, but it’s a long episode with lots of information about blue tigers, white tigers, black tigers, white lions, king cheetahs, and lots more. The third is about the Queensland tiger, an Australian animal that’s not a feline of any kind, but why not?

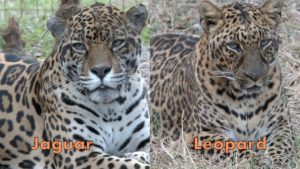

The term big cat refers to tigers, lions, leopards, snow leopards, and jaguars, but it can also include cheetahs and cougars depending on who you ask. Big cats have round pupils instead of slit pupils like domestic cats and other smaller cats.

Lions, tigers, leopards, and jaguars can all roar. Snow leopards, cheetahs, and cougars can’t. But snow leopards, cheetahs, and cougars can purr, while lions, tigers, leopards, and jaguars can’t. The ability to roar is due to special adaptations in the larynx, but these adaptations also mean big cats can’t purr. So basically a cat can either roar or purr but not both.

The word panther, incidentally, refers to any big cat and not to a specific type of animal. So a black panther, in addition to being an awesome movie, is any kind of big cat exhibiting melanism, which causes the animal’s fur to be black all over. Leopards and jaguars are most commonly referred to as black panthers. Lions, tigers, and cheetahs do not exhibit true melanism as far as researchers have found.

Let’s start with lions. Lions live only in Africa these days, but were once common throughout parts of southern Asia too and possibly even parts of southern Europe. The lion is most closely related to the leopard and jaguar, less closely related to the tiger and snow leopard, but it’s so closely related to all those big cats that it can interbreed with them in rare cases.

There are two species of lion, the African and the Asian. Until recently there were also several subspecies of African lions, including the American lion, which once lived throughout North and South America. It only went extinct around 11,000 years ago. The American lion is the largest subspecies of lion ever known, about a quarter larger than modern African lions. It probably stood almost four feet tall at the shoulder, or 1.2 meters. Cave paintings and pieces of skin preserved in caves indicate that its coat was reddish instead of golden. It lived in open grasslands like modern lions and even in cold areas. There are reports of a reddish, short-maned cat supposedly called a “jungle lion” sighted in South America, but I can’t find much information about it and it’s much more likely to be a jaguar or cougar than a relic population of American lions. But wouldn’t that be awesome if it was.

The Barbary lion was a subspecies of African lion that lived in northern Africa until it was hunted to extinction. The Barbary lion was the one that battled gladiators in ancient Rome and was hunted by pharaohs in ancient Egypt, a big lion with a dark mane. The last one was supposedly killed in 1922, but recent research indicates that they survived much longer—maybe as late as 1958 or later. The last recorded sighting was in 1956, but the forest where it was seen was destroyed two years later.

One zoo in Morocco claims that their lions are purebred Barbary lions, descended from royal lions kept in captivity for centuries. But since we don’t have a full genetic profile of the Barbary lion to start with, it’s hard to determine whether the royal lions are Barbary lions. So far a 2005 DNA test on five of the royal lions indicates they probably aren’t, but DNA testing has come a long way since then and new tests on the royal lions and on preserved Barbary lion skins will hopefully be done soon.

The Sumatran golden lion, also called the cigau [pronounced chee-gow] is a mystery lion that is supposed to be golden in color with no markings, a relatively short tail, and with a mane or ruff of fur that’s sometimes described as white. It’s only about the size of a small donkey or large goat, but stocky like a lion. The most recent sightings are from the 1960s, where one supposedly attacked and killed a man. Some researchers think it may be a subspecies of the nearly extinct Asiatic lion, but others say it’s more likely to be an animal of folklore. Then again, there are tigers on Sumatra and it’s always possible it’s an anomalous coated tiger with no stripes, or stripes that are almost the same color as its coat. Tigers do have a white ruff around the face.

Lions are well known to live on the savanna despite the term king of the jungle, but they do occasionally live in open forests and sometimes in actual jungles. In 2012 a lioness was spotted in a protected rainforest in Ethiopia, and locals say the lions pass through the reserve every year during the dry season. That rainforest is also one of the few places left in the world where wild coffee plants grow. So, you know, extra reason to keep it as safe as possible.

Let’s talk about tigers next. Tigers are awesome animals, with the Bengal tiger being the biggest big cat alive today—on average even bigger than the lion. Tigers are good swimmers and most really like the water, unlike most cats. They live throughout Asia but once were much more common and widespread. I’ve found a lot of mystery tiger reports, but if you’re interested in tigers of unusual colors, I really do recommend you go listen to the unlocked Patreon episode about blue tigers.

The so-called beast of Neamt is a modern mystery from Romania. In spring of 2016, farmers started finding livestock killed during the night, but not eaten. The predator was clearly extremely strong, much stronger and larger than a dog. Its method of killing didn’t suggest a bear, which locals were familiar with anyway.

Some of the sightings seem normal, of a catlike animal the size of a calf. Other sightings were more bizarre. Some people reporting seeing a huge animal running on two legs, one guy said he’d wounded it with an axe but it didn’t bleed, and of course there were the predictable reports that animals it killed were drained of blood.

But in this case, DNA testing solved the mystery of what was killing the animals. The beast was injured by a barbed-wire fence, and a test of its blood indicated it was a Siberian tiger. The Siberian tiger is also called the Amur tiger, which we talked about in episode 44, Extinct and Back from the Brink. But there are probably no more than 500 Siberian tigers alive in the wild, and none of them live within 3,000 miles of Romania, or 5,000 km. So while we know what the beast of Neamt is, we don’t know how it got there. Out of place tigers, hurrah!

Another mystery tiger is from Chad in Africa. This one is sometimes called the mountain tiger, and it’s supposed to be the size of a lion but with reddish fur, white stripes, no tail, and huge fangs.

This doesn’t sound like anything alive today—but it does sound like an extinct cat called Machairodus. It was the size of a lion, or over 3 feet tall at the shoulder, or 1 meter, and around 6 ½ feet long, or 2 meters. It was a type of saber-toothed cat like Smilodon, although it wasn’t closely related to Smilodon and its fangs weren’t as big. It probably had a short tail. But Machairodus and its relatives died out probably a million years ago, although it might have persisted to only 130,000 years ago. That’s still a lot of years, so it’s not too likely that a population of its descendants still lives in Chad. For one thing, northern Chad is part of the Sahara, while southern Chad is a savanna. It’s not dense jungle or remote mountains.

But there are similar reports of the mountain tiger in other parts of Africa, where there are steep mountain ranges that aren’t well explored. And, oddly enough, similar reports also come from South America and even from Mexico. Machairodus did live in Africa, Eurasia, and North America, although its fossils haven’t been found in South America. Maybe the reports aren’t of a living animal but were inspired by fossil remains. Hunters who stumbled across fossil machairodus bones would recognize them as similar to tiger or lion skeletons, but wouldn’t know that the living animal was long gone.

Another South American big cat report comes from Ecuador. It’s called the rainbow tiger or rainbow jaguar, and it sounds really pretty. In the Macas region in southeastern Ecuador, in the Amazon jungle, locals have a story about a big cat properly called Tshenkutshen. The cat is the size of a jaguar, or up to six feet long not counting the tail, or 1.85 meters, but instead of having a pattern of dark rosettes on a tawny background coat, the rainbow tiger is black with stripes on its chest. The stripes are different colors: white, red, yellow, and black, which gives it the rainbow name. One report I saw says it’s white with black spots in addition to the stripes on its chest. It lives in the trees in remote areas, is rare, and at least one report says it has a hump on its shoulders and monkey-like forepaws but with claws. One was supposedly shot and killed in 1959, but there are no pictures of the carcass and no one knows where it went, if it even existed in the first place.

Naturally, the rainbow tiger isn’t actually a tiger since tigers don’t live in South America. If it is a real animal and not a folktale, it’s probably a type of jaguar. But the whole monkey hands thing implies it’s probably more of a mythological creature than a flesh and blood one, because no feline of any kind has forepaws that resemble hands.

There’s an interesting addition to the rainbow tiger mystery. Dutch primatologist Dr. Marc van Roosmalen spotted a strange jaguar during an expedition through Brazil in the late 1990s. It was mostly black, but had a white pattern around its throat.

There are plenty of other South American big cat mysteries, including the yemish that we covered in episode 59 along with the onza, a mystery cat from Mexico and central America. But one especially interesting report is from Peru. Peter Hocking is a Peruvian ornithologist, or someone who studies birds, but he’s also interested in other animals. In 1996 he got his hands on two skulls that were similar to jaguar skulls but reportedly not from jaguars, but from strange striped big cats instead.

In 2010, zoologist Darren Naish asked for and finally received high-quality plaster replicas of the skulls so he could study them. His conclusion is that both skulls are actually from jaguars, but he points out that most big cat species do occasionally produce anomalously striped individuals. No one knows where the pelts of these two jaguars are, unfortunately. Hopefully they’ll turn up eventually, or another striped jaguar will be found and can be studied so we can learn if it’s just an individual with an anomalous coat pattern, or an actual subspecies of jaguar with stripes instead of spots.

I couldn’t find any mystery cheetah reports beyond one called the Tennessee red cheetah. That excited me because I live in Tennessee and I’d never heard of it before. The Tennessee red cheetah is supposed to resemble the cheetah, golden brown with black spots, but with a reddish dorsal stripe and tail. Some reports say it’s reddish-brown all over with black spots.

That’s it. That’s all the information I can find. I was so disappointed, but basically it sounds like a tall tale or maybe a sighting of a jaguar. That’s the problem with mystery big cat reports. There are so many reports of so many animals that don’t correspond to any known species or subspecies of big cat, with few concrete details. In the case of the Tennessee red cheetah, the only details I could find were vague stories about one being shot and skinned, but the skin was missing. No date, no place, no names, nothing.

You can’t treat a report like that with anything but skepticism, so let’s move on to another mystery big cat, the Zanzibar leopard. When I was making notes for this episode, I wrote “probably extinct, may be too depressing to use.” But there’s always a chance it’s not extinct.

The Zanzibar leopard lives on Zanzibar Island off of Tanzania. It’s not a big island, only around 50 miles long, or 85 km, and 20 miles wide, or 30 km. The Zanzibar leopard was probably separated from the mainland population of leopards when sea levels rose after the last ice age. It’s smaller than a mainland leopard, with smaller spots, but not much is known about it since it hasn’t been studied in the wild and it may be extinct now. Unfortunately, many people on the island believed that the leopards were witches’ familiars, and that they should be killed. In 1964 the islanders overthrew the government, but also unfortunately, the newly installed government persecuted people it decided were witches. This included a government-run campaign to kill all leopards on the island. By the mid-1990s, conservationists suspected the Zanzibar leopard was extinct.

But there is hope. Earlier this year an Animal Planet show caught footage on a camera trap of what appears to be a Zanzibar leopard. Hopefully there are still some of the leopards remaining, and if so, hopefully they can also be protected.

Speaking of Tanzania, let’s finish with a big cat that might very well be a real animal—or something even more mysterious. The nunda is supposed to be a huge gray cat with tabby stripes, reported in Tanzania. Its paw prints are supposed to resemble a leopard’s, but are as big as a lion’s.

In a 1927 article, a British administrator named William Hichens reported about his investigation into nunda attacks around the village of Lindi in Tanzania. The attacks occurred in 1922, and started with a night watchman who was found dead one morning. Clutched in the dead man’s hand was a tuft of gray fur that Hichens thought might have been torn from a lion’s mane. But lions were rare in that part of Tanzania, and two locals reported seeing a huge brindled cat attack the man during the night. A few nights after that, another watchman was also killed in the same way, including the tuft of hair clutched in one hand, and that was followed by more attacks in other villages over the next several weeks. The attacks stopped, but resumed in the 1930s. Some huge footprints and more of the gray fur were found by a British hunter who tried to track the animal.

So what might the nunda be? The description doesn’t sound like any known big cat. Cryptozoologist Bernard Heuvelmans suggested it might be a huge African golden cat with anomalous markings. The African golden cat is related to the caracal and the serval, both fairly small, long-legged cats. It has variable markings and coloring, from reddish to grey, from spotted to nearly plain. But it’s only about twice the size of a domestic cat. Its paws are large for its size, but it’s not anywhere near the size of a leopard, much less a lion.

Of course, it might be a larger subspecies of golden cat, or a totally different species. But there is another possibility, one that’s far creepier and darker than an unknown big cat.

According to a book called Wild Cats of the World by Mel and Fiona Sunquist, published in 2012, in the early 20th century a group of witch doctors in that part of Tanzania ran an extortion racket. They demanded money from people and threatened to turn into lions and kill them if they didn’t pay up. And they did kill people—over 100 of them, according to the book. The murders were committed by young men who dressed like lions, including wearing lion paws on their feet so they left lion paw prints.

That would explain the rash of murders in a localized area, and the fact that so many of the victims were found clutching gray fur. The fur was never tested and could have come from any animal and been planted on the victims.

Zoologist Karl Shuker suggests that if the deaths weren’t due to these lion-men, the mystery big cat might be a type of leopard with stripes instead of spots. Leopards with stripes due to genetic coat anomalies are extremely rare, but they aren’t unheard-of. They’re sometimes referred to as king leopards. I have a picture of one in the show notes. While leopards can cross-breed with tigers, tigers don’t live in Africa, so a striped leopard-tiger hybrid wouldn’t be hanging around in Tanzania, certainly not in the 1920s.

Whatever the cause, no one has reported a nunda sighting in about 80 years.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast online at strangeanimalspodcast.com. We’re on Twitter at strangebeasties and have a facebook page at facebook.com/strangeanimalspodcast. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. If you like the podcast and want to help us out, leave us a rating and review on Apple Podcasts or whatever platform you listen on. We also have a Patreon if you’d like to support us that way.

Thanks for listening!