Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 26:34 — 27.5MB)

Subscribe: | More

Talking animals! It’s not what you’re thinking about. No parrots here, just mammals.

Our new logo is by Susanna King of Flourish Media! If you’d like to JOIN OUR MAILING LIST!, I’ll be sending out a discount code soon for merch with our logo on it–but only for people on the mailing list (and patrons).

Further listening:

The MonsterTalk episode about Gef the Talking Mongoose (this episode has no swearing that I recall but some other episodes may have a little bit of salty language)

Mongolian Throat Singing

Further reading:

‘Talking’ seals mimic sounds from human speech, and validate a Boston legend

How do marine mammals produce sounds?

Elephant communication

Hoover the talking seal:

Janice, a gray seal who learned to mimic human speech and song:

Wikie, the orca who mimics human speech:

Kosik, an elephant who mimics human speech:

Gef the “talking mongoose”:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

Before we get started, I have some announcements! First, you may have noticed we have a new logo! It’s by Susanna King of Flourish Media, who did a fantastic job! Susanna is also a listener, which is awesome. I’ve put a link to Flourish Media in the show notes if you have a company or something that needs professional graphic design.

If you’re interested in getting a shirt or mug with the new Strange Animals Podcast logo on it, I’m figuring out the best company to use for merch. If you sign up to our mailing list, as soon as merch is available I’ll be sending an email out about it, and I’ll include a discount code you can use to save some money! I’ve linked to the mailing list in the show notes, and it’s also linked on the website and my social media, but if you can’t find it, just send me a message and I’ll reply with the link.

The final announcement is that my cat Poe is finally home and recovering from a scary illness. He developed what’s called pyothorax, which is an infection in the chest, and in Poe’s case we still don’t know what caused it. After a week in the veterinary intensive care unit, he’s finally home and getting better all the time. That’s why last week’s episode was so short, and if you messaged me this week about something and I seemed impatient when I replied, that’s why. I just haven’t had any mental energy to concentrate on anything but Poe. Thank you to everyone at the Animal Emergency and Specialty Center of Knoxville for taking such good care of him.

We’ve got something fun and a little different this time, inspired by two things. First, I saw a tweet about a captive beluga whale who had apparently learned to mimic human speech and one night told a diver in his pool to get out. Then the awesome podcast BewilderBeasts had a segment about a harbor seal in Maine who was rescued by a fisherman as a pup, which reminded me of a similar situation with another harbor seal in Maine, Hoover the Talking Seal. That’s right, it’s an episode about mammals that can talk, including one of my favorite cryptozoological mysteries ever.

Before we learn about talking animals, we need to learn a little bit about how humans talk. Humans produce most vocal sounds using our larynx, which is sometimes called a voicebox. The human larynx is situated at the top of the throat, and it helps us breathe, helps keep food from going down the wrong tube and into the lungs, and enables us to make sounds. It consists of cartilage, small muscles, and flaps of tissue called vocal folds or vocal cords. There are two kinds of vocal folds: the true vocal folds that are connected to muscles and actually produce sound, and the false vocal folds that don’t have any connected muscles and just help with resonance.

Usually resonance just makes the sound louder, but humans have learned to do amazing things with our voices. Some cultures use the false vocal folds to create a secondary tone. It’s called overtone singing, throat singing, or harmonic singing. I’m still completely in love with the Mongolian folk metal band the Hu and am now delighted that I can mention them again, because they use throat singing in their music. Throat singing produces overtones with various different sounds, depending on the technique used, but it can be hard to pick them out of a song if you’re not sure what you’re hearing. So instead of playing a clip of a Hu song, here’s a clip of a musician demonstrating various kinds of throat singing while also playing along on the morin khuur, or horsehead fiddle. The morin khuur only has two strings so the drone and whistle sounds you’re hearing are not from that instrument, they’re made by the musician’s voice. [Musician is Zagd Ochir AKA Sumiyabazar.]

[clip of throat singing]

When you think of animals that could potentially talk in human language, naturally you’d assume our closest relatives, the great apes, could learn to talk. But while apes have larynxes that are similar to ours, they don’t have the fine control over their vocal cords that humans do. But the larynx isn’t the only part of the body involved in human speech, it’s just the part that makes noise. We use the tongue and lips to form sounds into words, which takes a lot of fine control over very small muscles. Apes don’t have that kind of control of the mouth muscles. More importantly, they don’t have the same language centers in the brain that humans do. Apes can learn to use very simple versions of sign language or indicate words on a computer, but they aren’t able to use speech and language the way we do. In the wild, apes communicate with sounds, but they also communicate a lot more with gestures and body language, so they don’t need to speak words.

In the 1940s and 50s, a human couple who were both primate biologists worked with a young chimpanzee named Viki, trying to teach her spoken language as well as signs. While Viki was a quick learner and showed high intelligence, she only managed to ever speak seven words, and only four of those clearly. Those four words were mama and papa, cup, and up. I found a clip of Viki saying the word ‘cup,’ and while the audio was really bad, I don’t think she was actually vocalizing the word, just making the consonant sounds with her mouth.

But there are other animals that can mimic human speech, even if they don’t necessarily understand what they’re saying. Parrots and some other birds are the prime examples, of course, but we’re talking about talking mammals today.

Back in episode 23 I mentioned Hoover the talking seal and played this clip of his voice, one of only a few recordings we have of him.

[talking seal recording]

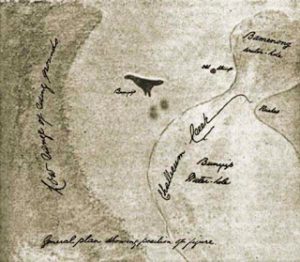

That may sound like a gruff man with a strong accent, but it’s a seal. In spring of 1971, in Cundy’s Harbor, Maine, which is in the extreme northeastern United States, a man found a baby harbor seal. He and his brother-in-law George Swallow hunted around for the seal pup’s mother, but sadly they found her dead body. George Swallow decided to take the baby seal home and see if he could keep him alive.

The baby seal ate so fast that Swallow and his wife named him Hoover, after the vacuum cleaner brand. Hoover stayed in a pond in the back of their house, and he not only survived, he did really well. Swallow basically treated Hoover like a dog and the two hung out together all the time. If Swallow had to go somewhere, Hoover rode along in the car. Before long, Hoover started imitating Swallow’s speech.

Finally, though, Hoover got so big and was eating so much fish that the Swallows couldn’t keep him. The New England Aquarium in Boston, Massachusetts agreed to take him in, and there Hoover stayed, happy and healthy until he died in 1985. When Swallow brought Hoover to the aquarium, he mentioned that the seal could talk. No one believed him. I wish I could have seen the keepers’ faces when Hoover first said, “Hello there!” in a voice that sounded just like George Swallow’s.

Here’s another clip of Hoover talking:

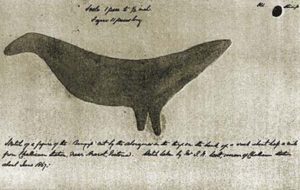

But if a chimpanzee can’t manage to speak human words, how can a seal? Seals of all kinds have a larynx that’s very similar to the human larynx, which allows a seal to physically imitate human vowel sounds. It also has the mental drive to imitate sounds and the mental flexibility to do a good job imitating sounds that aren’t normal seal noises. Seals are highly social animals and communicate with each other with a complex range of sounds.

A study published in 2019 focused on a trio of young gray seals, named Janice, Zola, and Gandalf, who learned to imitate vocal tones, even tunes, proving that Hoover’s ability to imitate his caregiver wasn’t just a fluke. The seals were released into the wild after a year. This is a clip of one of them singing in response to a computerized tune:

[clip of seal singing]

It’s not a coincidence that animals learn to imitate human speech while in captivity. Seals and other animals who communicate with sound learn to imitate what they hear most often. In wild animals, that’s almost always the calls of other animals of their own species, but animals in captivity often hear humans most of the time.

In the case of Wikie, an orca, or killer whale, she was taught to imitate human sounds by researchers. Wikie was born in captivity in 2001 and in 2018, researchers reported that they had taught her to imitate several words, including hello.

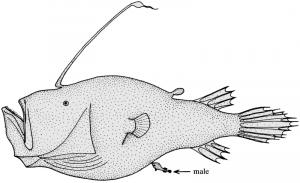

Whales and other cetaceans have very different anatomy from seals. They make lots of sounds, from clicks and whistles used for communication and navigation, to the incredibly loud, complex songs that some baleen whales use to attract mates. But they don’t always make those sounds with their larynx.

Toothed whales, including dolphins, make a lot of sounds with the blowhole, which is the specialized nostril at the top of the whale’s head that allows it to take a breath without having to stop moving or put its head out of the water. Toothed whales have specialized air sacs near the blowhole that allow a whale to make high-frequency sounds for echolocation, and it uses its larynx to make whistles and other noises. It may also clap its jaws together and slap the water with its tail or flippers to make sounds, especially ones that signal aggression.

Baleen whales have an inflatable pouch called the laryngeal sac that allows a whale to make extremely loud sounds with its larynx. Many animals have something similar to the laryngeal sac, including some primates. If you remember episode 76, where we talked about the siamang, a type of gibbon, it has a throat pouch called a gular sac that increases the resonance and loudness of its voice.

Orcas in particular imitate sounds made by other orcas, so much so that when an orca pod moves into new territory, it will adopt the sounds made by the local orcas. They will also imitate the sounds made by sea lions and bottlenose dolphins. It’s not surprising, then, that Wikie was able to learn to imitate human words. Here’s some audio of Wikie saying hello (sort of):

[orca speech]

Another mammal that can learn to imitate human speech, at least occasionally, is the elephant! One famous talking elephant is Kosik [koh-shik], an Indian elephant in South Korea who has learned to say yes, no, sit, and several other words, in Korean of course. Kosik puts the tip of his trunk in his mouth and exhales while moving his trunk around to produce the sounds.

The elephant does use its larynx to make sounds, but it also has the option to use its trunk as a resonant chamber to make the sounds deeper. Some of the sounds an elephant makes are below the range of human hearing, as are many sounds baleen whales make. The elephant’s larynx is especially flexible too compared to most mammals, and as if its trunk wasn’t enough, it also has a pharyngeal pouch at the base of the tongue that it uses to produce low frequency calls.

This pharyngeal pouch is different from the baleen whale’s laryngeal sac and the siamang’s gular sac, although all three are used for similar purposes. The elephant actually stores water in the pouch, several liters of water. If an elephant can’t find water and is thirsty, it will stick its trunk deep into its mouth and into the pouch, then constrict the muscles around the pouch to push the water up. Then it can drink the water. It’s like having a built-in water bottle that also allows you to make deep noises.

Batyr was another elephant who reportedly learned to imitate some words and phrases, these in Russian and Kazakh. He lived in a zoo in Kazakhstan until his death in 1993. Like Kosik, Batyr produced the words by sticking his trunk in his mouth, with one keeper reporting that he actually moved his tongue into place with his trunk to make the right sounds. It’s possible that’s exactly what he was doing, since an elephant’s trunk is much more dexterous than an elephant’s tongue. He would also sometimes imitate other animals heard in the zoo.

All the animals we’ve discussed so far were only imitating human words. While they may have learned to use the words appropriately, for instance saying the word water when they wanted a drink, there’s no evidence that any of these animals truly understood the meaning of the words they learned to imitate. But there is one talking animal that was supposed to understand every word he said, a strange and elusive animal only seen by a few people but heard by many more. He’s called Gef the talking mongoose, and he’s one of my very favorite cryptids.

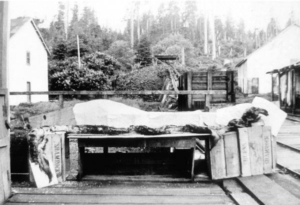

Gef’s story starts in 1931 on the Isle of Man, a British island in the Irish Sea. A family lived in a remote farmhouse near the village of Darby: James Irving (who went by Jim), his wife Margaret, and their twelve-year-old daughter Voirrey. They also had a sheepdog named Mona. The house was a big stone one with wood paneling inside, but with a gap between the stone and wood. These days that would be where the insulation would go to keep the house warmer, but this was before modern insulation and as far as I’ve read the gap was empty. The house didn’t have electricity either.

One night in 1931 the family heard an animal rustling and scratching around inside the gap. This probably wasn’t an unusual occurrence, since there are mice and rats on the Isle of Man along with stoats and ferrets. Any of those might decide to investigate the house and make a little home in the gap between the outer and inner walls.

In this case, though, the animal started out making little animal sounds but soon started trying to talk. At first it sounded like a baby babbling, but within a few weeks it was speaking clearly in English.

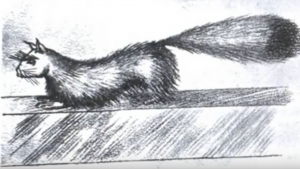

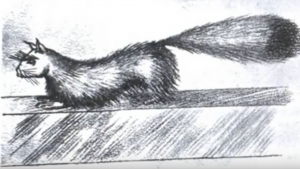

The family didn’t know what to think. At first they actually tried to poison the animal, but before long they made peace with it and named him Gef. They rarely saw Gef, just talked to him through the walls. Occasionally they’d see a bright eye peering at them through a knothole or see Gef outside, whisking across the fields. He wasn’t very big, only about a foot long, or 30 cm, including his bushy tail. He was yellowish in color with a slender ferret-like body, and his tail had a black tip. But he wasn’t a ferret, and apparently his front feet were shaped more like tiny human hands than like an animal’s paws. Gef described himself as a mongoose, specifically, “a little extra, extra clever mongoose.”

The weird thing is, there were mongooses on the Isle of Man at the time even though the mongoose is native to Africa, southern Asia, and southern Europe—but only where it’s warm most of the time. They certainly don’t live on the Isle of Man ordinarily. A man who owned a neighboring farm had imported some to kill rabbits, since there are no foxes on the island to keep the rabbit population down. There are even occasional sightings of what might be mongooses on the island today. The mongoose resembles mustelids like weasels and ferrets, but isn’t very closely related to them, and some species are yellowish in color. But the mongoose is much larger than Gef and has a more tapered tail. Also, mongooses don’t actually talk.

The meerkat is a type of mongoose, so if you ever watched Meerkat Manor you know a lot about mongooses already.

Anyway, Gef was clearly not actually a mongoose. The question is whether he was a real animal at all. In many ways, he had more in common with supernatural entities like poltergeists and brownies than with ordinary animals. He sometimes seemed to know about things before they happened, he seemed able to vanish when he didn’t want to be seen, and he made fantastic claims about his history. He also sprinkled words and phrases from other languages into his speech.

At the time, most people on the island thought Voirrey had invented Gef for attention, or maybe in an attempt to get her family to move somewhere more comfortable. She didn’t like living on a farm where the nearest neighbor was two miles away. But Voirrey claimed to the very end of her life—and she lived until 2005—that she hadn’t invented Gef and in fact Gef had ruined her life in some ways. She was teased about him in school and hated all the attention surrounding him, so much so that when she grew up and moved away, she actually changed her name to try and avoid any further publicity. She almost never gave interviews about Gef, and her family certainly never made any money off their resident talking animal even though they were very poor.

These days, a lot of suspicion focuses on Voirrey’s father, Jim Irving. Almost all of the information we have about what Gef said and did comes from Jim’s diaries and letters. He wrote a lot about Gef and apparently planned to write a book about the family’s experiences. The famous investigator of mysterious phenomena, Harry Price, told Jim there was no money in a book about Gef—and then promptly published his own book about Gef, which was a mean trick. Harry Price thought Voirrey was speaking as Gef by somehow throwing her voice, probably by using the acoustic properties of the double-walled house.

It’s possible, of course, that Gef was invented by Jim as a way to make Voirrey happier about having little animals scrabbling about in the walls. It might have started as a family joke that got out of control when people outside the family heard about it. Jim sounds like he was a little bit of a showman and had big dreams. He might have decided that his little family in-joke about Gef the talking mongoose would make a good book, and started spreading the story around as though it was real. Before long, people were swarming to his farmhouse to listen for Gef, Voirrey was being teased and blamed for the phenomenon, and people were demanding proof that Gef was real. Jim couldn’t admit he’d made the whole thing up and risk everyone getting angry.

Jim had traveled widely when he was younger and knew a smattering of words from other languages—the same words that Gef sprinkled into his speech. And remember, Jim is the main source of information about Gef. I wonder if Voirrey understood that her father had painted himself into a corner by telling people about Gef, because she tried to help prove the talking mongoose was real. She produced some hairs she said came from Gef, but when analyzed they were found to be identical to Mona the sheepdog’s fur. Voirrey produced some footprints and tooth prints supposedly made by Gef in plasticine, but they look a lot like they were made by someone poking designs into the plasticine with a sharp stick.

Gef became less and less active over the years, disappearing for months at a time, and by 1939 he was pretty much gone. Voirrey was grown by then and probably long tired of the joke. Jim died in 1945.

Whatever or whoever was behind the talking mongoose story, it’s definitely fun to think about. Gef was snarky, clever, sometimes funny, always weird. For instance, when Jim told Gef “We are having a dictaphone to record your voice,” Gef replied, “Who’s we? Is it that spook man Harry Price? Why, I won’t speak into it. I’ll go and smash his windows. I’ll drop a brick on him as he lies in bed. Me, at the age of 83?” Gef claimed he was born in India on June 7, 1852. Sometimes he said he was an earthbound spirit, sometimes he said he was not a spirit, just a mongoose. Once he said, “I am a ghost in the form of a weasel, and I shall haunt you with weird noises and clanking chains.” Mostly, though, he just recounted village gossip and demanded treats. Occasionally he killed a rabbit and left it for Voirrey like a pet cat leaving a mouse for its owner.

If my cats could speak, I’m pretty sure Poe would be complaining nonstop about having to be in the hospital for a whole week. Actually, he is complaining nonstop about it, just not in actual words. But I understand him anyway.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. If you like the podcast and want to help us out, leave us a rating and review on Apple Podcasts or Podchaser, or just tell a friend. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us that way.

Thanks for listening!