Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 15:38 — 16.1MB)

Thanks to Pranav for his suggestion! Let’s find out what the river of giants was and what lived there!

Further reading:

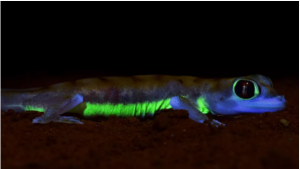

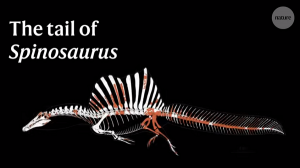

Spinosaurus was a swimming dinosaur and it swam in the River of Giants:

A modern bichir, distant relation to the extinct giants that lived in the River of Giants:

Not actually a pancake crocodile:

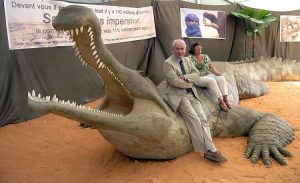

A model of Aegisuchus and some modern humans:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

A while back, Pranav suggested we do an episode about the river of giants in the Sahara. I had no idea what that was, but it sounded interesting and I put it on the list. I noticed it recently and looked it up, and oh my gosh. It’s amazing! It’s also from a part of the world where it’s really hot, as a break for those of us in the northern hemisphere who are sick of all this cold weather. I hope everyone affected by the recent winter storms is warm and safe or can get that way soon.

The Sahara is a desert in northern Africa, famous for its harsh climate. Pictures of the Sahara show its huge sand dunes that stretch to the horizon. This wasn’t always the case, though. Only about 5,500 years ago, it was a savanna with at least one lake. Lots of animals lived there and some people too. Before that, around 11,000 years ago, it was full of forests, rivers, lakes, and grasslands. Before that, it was desert again. Before that, it was forests and grasslands again. Before that, desert.

The Sahara goes through periodic changes that last around 20,000 years where it’s sometimes wet, sometimes dry, caused by small differences in the Earth’s tilt which changes the direction of the yearly monsoon rains. When the rains reach the Sahara, it becomes green and welcoming. When it doesn’t, it’s a desert. Don’t worry, we only have 15,000 more years to wait until it’s nice to live in again.

This wet-dry-wet pattern has been repeated for somewhere between 7 and 11 million years, possibly longer. Some 100 million years ago, though, the continents were still in the process of breaking up from the supercontinent Gondwana. Africa and South America were still close together, having only separated around 150 million years ago. The northern part of Africa was only a little north of the equator and still mostly attached to what is now Eurasia.

Near the border of what is now Morocco and Algeria, a huge river flowed through lush countryside. The river was home to giant animals, including some dinosaurs. Their fossilized remains are preserved in a rock formation called the Kem Kem beds, which run for at least 155 miles, or 250 km. A team of paleontologists led by Nizar Ibrahim have been working for years to recover fossils there despite the intense heat. The temperature can reach 125 degrees Fahrenheit there, or 52 Celsius, and it’s remote and difficult to navigate.

For a long time researchers were confused that there were so many fossils of large carnivores associated with the river, more than would be present in an ordinary ecosystem. Now they’ve determined that while it looks like the fossils were deposited at roughly the same time from the same parts of the river, they’re actually from animals that lived sometimes millions of years apart and in much different habitats. Bones or even fossils from one area were sometimes exposed and washed into the river along with newly dead river animals. This gives the impression that the river was swarming with every kind of huge predator, but it was probably not quite so dramatic most of the time.

Then again, there were some really fearsome animals living in and around the river in the late Cretaceous. One of the biggest was spinosaurus, which we talked about in episode 170. Spinosaurus could grow more than 50 feet long, or 15 m, and possibly almost 60 feet long, or 18 m. It’s the only dinosaur known that was aquatic, and we only know it was aquatic because of the fossils found in the Kem Kem beds in the last few years.

Another dinosaur that lived around the river is Deltadromeus, with one incomplete specimen found so far. We don’t have its skull, but we know it had long, slender hind legs that suggests it could run fast. It grew an estimated 26 feet long, or 8 meters, including a really long tail. At the moment, scientists aren’t sure what kind of dinosaur Deltadromeus was and what it was related to. Some paleontologists think it was closely related to a theropod dinosaur called Gualicho, which lived in what is now northern Patagonia in South America. Remember that when these dinosaurs were still alive, the land masses we now call Africa and South America had been right in the middle of a supercontinent for hundreds of millions of years, and only started separating around 150 million years ago. Gualicho looked a lot like a pocket-sized Tyrannosaurus rex. It grew up to 23 feet long, or 7 meters, and had teeny arms. Deltadromeus’s arms are more in proportion to the rest of its body, though.

Some of the biggest dinosaurs found in the Kem Kem beds are the shark-toothed dinosaurs, Carcharodontosaurus, nearly as big as Spinosaurus and probably much heavier. It grew up to 40 or 45 feet long, or 12 to almost 14 meters, and probably stood about 12 feet tall, or 3 ½ meters. It had massive teeth that were flattened with serrations along the edges like steak knives. The teeth were some eight inches long, or 20 cm.

Researchers think that Carcharodontosaurus used it massive teeth to inflict huge wounds on its prey, possibly by ambushing it. The prey would run away but Carcharodontosaurus could take its time catching up, following the blood trail and waiting until its prey was too weak from blood loss to fight back. This is different from other big theropod carnivores like T. rex, which had conical teeth to crush bone.

Dinosaurs weren’t the only big animals that lived in and around the River of Giants, of course. Lots of pterosaur fossils have been found around the river, including one species with an estimated wingspan of as much as 23 feet, or 7 meters. There were turtles large and small, a few lizards, early snakes, frogs and salamanders, and of course fish. Oh my goodness, were there fish.

The river was a large one, possibly similar to the Amazon River. In the rainy season, the Amazon can be 30 miles wide, or 48 km, and even in the dry season it’s still two to six miles wide, or 3 to 9 km. The Amazon is home to enormous fish like the arapaima, which can grow up to 10 feet long, or 3 m. Spinosaurus lived in the River of Giants, and that 50-foot swimming dinosaur was eating something. You better bet there were big fish.

The problem is that most of the fish fossils are incomplete, so paleontologists have to estimate how big the fish was. There were lungfish that might have been six and a half feet long, or 2 meters, a type of freshwater coelacanth that could grow 13 feet long, or 4 meters, and a type of primitive polypterid fish that might have been as big as the modern arapaima. Polypterids are still around today, although they only grow a little over three feet long these days, or 100 cm. It’s a long, thin fish with a pair of lungs as well as gills, and like the lungfish it uses its lungs to breathe air when the water where it lives is low in oxygen. It also has a row of small dorsal fins that make its back look like it has little spikes all the way down. It’s a pretty neat-looking fish, in fact. They’re called bichirs and reedfish and still live in parts of Africa, including the Nile River.

There were even sharks in the river of giants, including a type of mackerel shark although we don’t know how big it grew since all we have of it are some teeth. Another was a type of hybodont shark with no modern descendants, although again, we don’t know how big it was.

The biggest fish that lived in the River of Giants, at least that we know of so far, is a type of ray that looked like a sawfish. It’s called Onchopristis numidus and it could probably grow over 26 feet long, or 8 meters. Its snout, or rostrum, was elongated and spiked on both sides with sharp denticles. It was probably also packed with electroreceptors that allowed it to detect prey even in murky water. When it sensed prey, it would whip its head back and forth, hacking the animal to death with the sharp denticles and possibly even cutting it into pieces. Modern sawfish hunt this way, and although Onchopristis isn’t very closely related to sawfish, it looked so similar due to convergent evolution that it probably had very similar habits.

The modern sawfish mostly swallows its prey whole after injuring or killing it with its rostrum, although it will sometimes eat surprisingly large fish for its size, up to a quarter of its own length. A 26-foot long Onchopristis could probably eat fish over five feet long, or 1.5 meters. It wouldn’t have attacked animals much larger than that, though. It wasn’t eating fully grown Spinosauruses, let’s put it that way, although it might have eaten a baby spinosaurus from time to time. Spinosaurus might have eaten Onchopristis, though, although it would have to be pretty fast to avoid getting injured.

But there was one other type of animal in the River of Giants that could have tangled with a fully grown spinosaurus and come out on top. The river was full of various types of crocodylomorphs, some small, some large, some lightly built, some robust. Kemkemia, for instance, might have grown up to 16 feet long, or 5 meters, but it was lightly built. Laganosuchus might have grown 20 feet long, or 6 meters, but while it was robust, it wasn’t very strong or fast. It’s sometimes called the pancake crocodile because its jaws were long, wide, and flattened like long pancakes. Unlike most pancakes, though, its jaws were lined with lots and lots of small teeth that fit together so closely that when it closed its mouth, the teeth formed a cage that not even the tiniest fish could escape. Researchers think it lay on the bottom of the river with its jaws open, and when a fish swam too close, it snapped it jaws closed and gulped down the fish. But obviously, the pancake crocodile did not worry spinosaurus in the least.

Aegisuchus, on the other hand, was simply enormous. We don’t know exactly how big it is and estimates vary widely, but it probably grew nearly 50 feet long, or 15 meters. It might have been much longer, possibly up to 72 feet long, or 22 meters. It’s sometimes called the shield crocodile because of the shape of its skull.

We don’t have a complete specimen of the shield crocodile, just part of one skull, but that skull is weird. It has a circular raised portion called a boss made of rough bone, and the bone around it shows channels for a number of blood vessels. This is unique among all the crocodilians known, living and extinct, and researchers aren’t sure what it means. One suggestion is that the boss was covered with a sheath that was brightly colored during the mating season, or maybe its shape alone attracted a mate. Modern crocodilians raise their heads up out of the water during mating displays.

The shield crocodile had a flattened head other than this boss, and its eyes may have pointed upward instead of forward. If so, it might have rested on the bottom of the river, looking upward to spot anything that passed overhead. Then again, it might have floated just under the surface of the water near shore, looking up to spot any dinosaurs or other land animals that came down to drink. Watch out, dinosaur! There’s a crocodilian!

Could the shield crocodile really have taken down a fully grown spinosaurus, though? If it was built like modern crocodiles, yes. Spinosaurus was a dinosaur, and dinosaurs had to breathe air. If the shield crocodile hunted like modern crocs, it was some form of ambush predator that could kill large animals by drowning them. You’ve probably seen nature shows where a croc bursts up out of the water, grabs a zebra or something by the nose, and drags it into the water, quick as a blink. The croc can hold its breath for up to an hour, while most land animals have to breathe within a few minutes or die. The shield crocodile and spinosaurus also lived at the same time so undoubtedly would have encountered each other.

Then again, there’s a possibility that the shield crocodile wasn’t actually very fearsome, no matter how big it was. It might have been more lightly built with lots of short teeth like the pancake crocodile’s to trap fish in its broad, flattened snout. Until we have more fossils of Aegisuchus, we can only guess.

Fortunately, palaeontologists are still exploring the Kem Kem beds for more fossils from the river of giants. Hopefully one day soon they’ll find more shield crocodile bones and can answer that all-important question of who would win in a fight, a giant crocodile or a giant swimming dinosaur?

You can find Strange Animals Podcast at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. If you like the podcast and want to help us out, leave us a rating and review on Apple Podcasts or just tell a friend. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us that way and get twice-monthly bonus episodes as well as stickers and things.

Thanks for listening!