Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 22:56 — 23.7MB)

This week we’re going to learn about elephants! Thanks to Damian, Pranav, and Richard from NC for the suggestions!

Further Reading:

Dwarf Elephant Facts and Figures

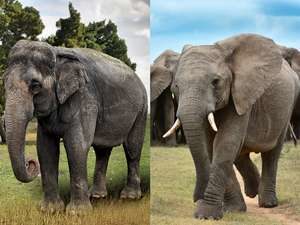

An Asian elephant (left) and an African elephant (right). Note the ear size difference, the easiest way to tell which kind of elephant you’re looking at:

Business end of an Asian elephant’s trunk:

An elephant living the good life:

Can’t quite reach:

Elephant teef:

A dwarf elephant skeleton:

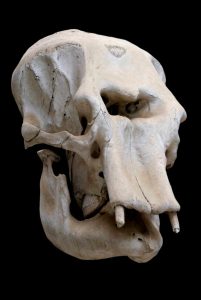

An elephant skull does kind of look like a giant one-eyed human skull:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

This week we’re going to learn about some elephants! We’ve talked about elephants many times before, but not recently, and we’ve not really gone into detail about living elephants. Thanks to Damian, Pranav, and Richard from NC for the suggestions. Damian in particular sent this suggestion to me so long ago that he’s probably stopped listening, probably because he’s grown up and graduated from college and started a family and probably his kids are now in college too, it’s been so long. Okay, it hasn’t been that long. It just feels like it. Sorry I took so long to get to your suggestion.

Anyway, Damian wanted to hear about African and Asian elephants, so we’ll start there. Those are the elephants still living today, and honestly, we are so lucky to have them in the world! If you’ve ever wished you could see a live mammoth, as I often have, thank your lucky stars that you can still see an elephant.

Elephants are in the family Elephantidae, which includes both living elephants and their extinct close relations. Living elephants include the Asian elephant and the African elephant, with two subspecies, the African savanna elephant and the African forest elephant. The savanna elephant is the largest.

The tallest elephant ever measured was a male African elephant who stood 13 feet high at the shoulder, or just under 4 meters, which is just ridiculously tall. That’s two Michael Jordans standing on top of each other, and I don’t know how you would clone Michael Jordan or get one of them to balance on the other’s head, but if you did, they would be the same size as this one huge elephant. The largest Asian elephant ever measured was a male who stood 11.3 feet tall, or 3.43 meters. Generally, though, it’s hard to measure how tall or heavy a wild elephant is because first of all they don’t usually want anything to do with humans, and second, where are you going to get a scale big and strong enough to weigh an elephant? Most male African elephants are closer to 11 feet tall, or 3.3 meters, while females are smaller, and the average male Asian elephant is around 9 feet tall, or 2.75 meters, and females are also smaller. Even a small elephant is massive, though.

Because of its size, the elephant can’t jump or run, but it can move pretty darn fast even so, up to 16 mph, or 25 km/h. The fastest human ever measured was Usain Bolt, who can run 28 mph, or 45 km/h, but only for very short distances. A more average running speed for a person in good condition is about 6 mph, or 9.6 km/h, and again, that’s just for short sprints. So the elephant can really hustle. Its big feet are cushioned on the bottoms so that it can actually move almost noiselessly. And I know you’re wondering it, so yes, an elephant could probably be a good ninja if it wanted to. It would have to carry its sword in its trunk, though. The elephant is also a really good swimmer, surprisingly, and it can use its trunk as a snorkel when it’s underwater. It likes to spend time in the water, which keeps it cool, and it will wallow in mud when it can. The mud helps protect it from the sun and from insect bites. Its skin is thick but it’s also sensitive, and it doesn’t have a lot of hair to protect it.

The elephant is a herbivore that only eats plants, but it eats a lot of them. An adult elephant eats several hundred pounds of food a day, or more than 100 kg, and will drink enough water every day to fill a bathtub. It eats grass, leaves, twigs, fruit, and bark, and elephants in captivity also eat hay. And since we’re getting close to the winter holidays, some zoos have an agreement with Christmas tree sellers, who donate any unsold Christmas trees to the zoos for the elephants to eat. They can’t feed used trees because there might be leftover ornaments or ornament hangers on them. The elephant just puts one foot on the tree and rips off the branches with its trunk, which it then eats.

The elephant has a pair of big teeth on each side of its mouth that look more like the bottoms of running shoes than ordinary teeth, which it uses to grind up the tough plants it eats. Elephants technically have 26 teeth, two incisors and 24 molars. The incisors are modified into tusks, which we’ll talk about in a minute. The molars aren’t all in the mouth at once, though. Every so many years, the four molars in an elephant’s mouth start to get pushed out by four new molars. It doesn’t happen the same way you lose your baby teeth, though. Instead of a new tooth pushing up through the gum until the baby tooth gets loose and falls out, the new molars grow in at the back of the mouth and start moving forward, pushing the old molars farther forward until they fall out. This happens six times throughout the elephant’s life, with the last set usually growing in around the early 40s. Since elephants can live much longer than that, well into their sixties, that last set may have to last a long time, since there are no elephant dentists that can make gigantic elephant dentures.

The tusks are much different than the molars, naturally. The tusks start to grow from the upper jaw when the elephant is a little over six months old, and continue growing throughout its life. It uses its tusks for all kinds of activities, including moving obstacles from its path, digging for water, and defending itself. But not all elephants have tusks. Many Asian elephants don’t have tusks at all, or only have very small ones. Because poachers who want the tusks to sell as ivory shoot elephants that have the biggest tusks, many populations now have smaller tusks overall or none, since elephants without them are less likely to be killed.

The elephant’s trunk is strong but sensitive, sort of like a human’s arm and hand but with many more uses (and also no bones). The elephant breathes and smells through its trunk, since it’s an extension of the nose and upper lip, but it also makes noise with its trunk to communicate with other elephants, uses it to gather food and move it into the mouth, sucks up water with the trunk and splooshes it into the mouth to drink or onto its body to wash. It can reach plants that are way up high or it can dig into soft ground for roots or to reach water. It can open nuts with its trunk, scratch an itch, play wrestle with a friend, lift incredibly heavy things out of the way, and all sorts of other things. Elephants probably wonder how humans can function without a trunk. I am starting to wonder how I function without a trunk.

The easiest way to tell an Asian elephant apart from an African elephant is by looking at the ears. African elephants have much larger ears, especially savanna elephants. The ears are full of small blood vessels to help release heat from the body into the atmosphere. An elephant will flap its ears to stay cool on a hot day. Asian elephants are also smaller overall and have a different body shape. Asian elephants have somewhat shorter legs, a bulkier forehead, different numbers of toes on the feet, and even different trunks. The African elephant has two little projections at the tip of the trunk that act as fingers, while the Asian elephant only has one.

Elephants evolved in what is now Africa and are the largest land animals alive today. The earliest elephant ancestors lived around 56 million years ago, not long after the extinction of the non-avian dinosaurs. It was still a small animal then, only about a foot tall at the shoulder, or 30 cm. It probably spent a lot of time in the water, eating plants, and it probably had small ears and a large nose, but not an actual trunk. If you could go back in time and look at it, you’d never guess that it was an ancestral elephant.

By 27 million years ago, though, elephant ancestors were starting to look like elephants. Eritreum was a lot bigger, over four feet tall at the shoulder, or 1.3 meters, and it probably had short tusks and a trunk. If you looked at a living Eritreum, you’d definitely know it was a kind of elephant, even though it would have looked weird compared to modern elephants since its head was long and flattened in shape. Eritreum already had the same tooth system that modern elephants have, where new molars continually grow and replace worn-out older ones.

Eritreum’s descendants spread to Eurasia and then to North America. By about 2.5 million years ago, at the beginning of the Pleistocene, elephants were all over the place–not just the ancestors of modern elephants, but relations from other parts of the elephant family tree. This includes Palaeoloxodon, a suggestion by Richard from NC.

Palaeoloxodon namadicus lived throughout much of Asia, with fossils found in India, Japan, and Sri Lanka, and it was enormous. We don’t have a complete skeleton, but estimates of Palaeoloxodon’s size suggest it was the largest elephant that we’ve ever discovered. An estimate of the largest specimen found so far is 17.1 feet tall at the shoulder, or 5.2 meters. This is about the same height at the shoulder as Paraceratherium, which we talked about in episode 50 about tallest animals, but it might have actually been taller than Paraceratherium. The tallest giraffe ever measured was 19.3 feet tall, or 5.88 meters, but that’s at the top of its head, not its shoulder, and giraffes are much less heavy than elephants. Whichever one was actually tallest doesn’t really matter, though, because they all belong to the Ridiculously Tall Animals Club, also known as the Animals That Could Squish You Flat by Accident Club.

We don’t know much about Palaeoloxodon since so few fossils have been found so far. We mostly just know it was a massive animal that probably went extinct 24,000 years ago. That’s really not that long ago in geologic terms. It was probably a member of the straight-tusked elephants, a group of animals that were mostly quite large even for elephants.

Straight-tusked elephants weren’t actually straight-tusked, just straighter than most elephant tusks. They all also had an unusual feature on the head called a parieto-occipital crest, which was a ridge of bone high up on the forehead above the eyes that jutted out. The crest was barely noticeable in young elephants but grew larger as the elephant matured, and researchers think it was the attachment site for massive neck muscles to hold up the animal’s massive head.

One interesting thing about Palaeoloxodon is that some other members of the genus were dwarf species that lived on some Mediterranean islands. Pranav wanted to learn about these and other pygmy elephants of the Mediterranean Islands. Fossil elephants have been found on many islands, including islands in the Mediterranean, in south Asia, and the Channel Islands off the coast of California, although they weren’t all closely related. I think we’ve talked about insular dwarfism before, but let’s go over it again briefly. When a large animal like an elephant becomes restricted to a small environment, like an island, there aren’t enough resources for a full population of full-grown animals. As a result, only smaller individuals get enough food to thrive well enough to reproduce, which means their babies are more likely to be smaller too. Over time this results in a population of animals that are much smaller than their relations who don’t live in a restricted environment.

The opposite of insular dwarfism is island gigantism, by the way. When species that are small ordinarily, like pigeons, colonize an island where there are plenty of resources and very few or no predators, they evolve into much larger animals, like dodos.

Insular dwarfism isn’t just about mammals. Palaeontologists have identified dwarf species of dinosaur too, including a pocket-sized sauropod. Okay, maybe not pocket-sized since they still grew nearly 20 feet long, or 6 meters, but since their mainland relations could grow 100 feet long, or 30 meters, that’s a big difference.

Anyway, back to dwarf elephants. It’s so easy to get distracted by all this neat information. The elephants that lived in the Mediterranean islands were mostly straight-tusked elephants, although at least one was a type of mammoth. During the Pleistocene, when a lot of the world’s water was frozen in enormous glaciers, the sea levels were much lower. This exposed a lot more land, and of course animals lived on that land. Then, during the interglacial periods when much of the ice melted and sea levels rose, animals moved to higher ground and eventually some were cut off from the mainland and lived on islands. All of these species that survived exhibited insular dwarfism. It’s helpful to remember that the islands we’re talking about are mostly pretty big. I mean, they’re not the size of Gilligan’s Island. People live on many of these islands today and there are cities and towns and farms and national parks and so forth. The island of Crete, for instance, which is a part of Greece, is 3,260 square miles in size, or 8,450 square km.

One dwarf elephant that once lived on Crete may have only grown 3.7 feet tall at the shoulder, or 1.13 meters. That was the mammoth relation, but a species of Palaeoloxodon also lived on Crete, although not necessarily at the same time as the dwarf mammoth. As the sea levels rose and fell over the centuries, different species of elephant and other animals ended up living on the islands at different times.

We don’t know a whole lot about these dwarf elephants, unfortunately, since we don’t have a lot of remains. Mostly we have teeth, which do tell a lot about the elephant but not everything. But we do know roughly when the various species finally went extinct, and you will not be surprised to learn that these dates often coincide with human arrival on the islands. The Tilos Island elephant probably didn’t go extinct until 6,000 years ago. That’s well into the modern era, and humans lived or at least hunted on the island starting around 10,000 years ago. If you are Greek, your ancestors may have hunted Tilos Island dwarf elephants. It grew up to around 5 feet 3 inches tall, or 1.6 meters, which coincidentally is my height.

Many historians think that the bones and fossils of dwarf elephants may have led to the legend of the cyclops in ancient Greece. The skull of an elephant has a big opening in the front for the nasal passages, with relatively small eye sockets on the sides of the skull. If you’re not familiar with living elephants and you see an elephant skull, it really does look like an enormous human skull with one eye socket in the middle of the forehead.

All elephants live in small family groups that consist of a leader, called the matriarch, who is usually the oldest female in the group, and her close relations and their babies, usually her daughters and grandchildren. When a young male elephant grows up, he leaves his family group, but daughters usually stay.

Although elephants live in these small groups, they’re social animals. The family groups interact with each other when they meet, and they may meet up purposefully just to say hi. A family with a lot of babies may meet up with another family for help taking care of the young ones. When a member of the group is in estrus, meaning she can get pregnant, local males will join the group and try to get her attention. But although the males don’t spend all their time with family groups, they make friends with other males and sometimes form small bachelor groups of their own led by an older male. The older male not only teaches the younger ones how to find food and react to danger, he keeps them from running wild and acting up. During the 1990s, a nature reserve in South Africa introduced a lot of young males that were orphaned and had no family–but without an older male to keep them in line, they went on a rampage and killed 36 rhinoceroses. Finally the park introduced an older male and he put a stop to all that. The young elephants straightened up and left the rhinos alone.

Females usually come into estrus during the rainy season, which is in the second half of the year in Asia and parts of Africa. During this time, mature males may enter a condition called musth for at least some of the time. During musth a male is more aggressive and struts around showing off. It’s easy to tell when a bull elephant is in musth because a gland on each side of his face releases fluid that makes his cheeks wet. Females prefer to mate with males in musth, and usually in a group of males only the most dominant male will be in musth.

Elephants these days are all threatened by poaching, especially for their tusks. Elephant tusks are known as ivory, and ivory sales are banned throughout most of the world. Unfortunately, people still kill elephants to sell the ivory on the black market. Elephants are also threatened by habitat loss, since they need a whole lot of land to find enough to eat and people want that land for their domestic animals or crops.

I could go on and on about elephants for hours. There’s so much to learn about them that it’s just not possible to fit into one podcast episode. I haven’t even touched on their intelligence, their use as working animals in Asia and other parts of the world, and many other interesting things. But we’ll finish with this interesting fact: elephants are afraid of bees, so farmers can keep elephants from eating their crops by making a fence out of bee hives.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. If you like the podcast and want to help us out, leave us a rating and review on Apple Podcasts or just tell a friend. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us that way.

Thanks for listening!