Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 13:31 — 15.4MB)

Thanks to Page for suggesting we talk about penguins this week!

A big birthday shout-out to EllieHorseLover this week too!

Further reading:

March of the penguins (in Norway)

Rare Yellow Penguin Bewilders Scientists

Giant Waikato penguin: school kids discover new species

An ordinary king penguin with the rare “yellow” king penguin spotted in early 2021 (photo by Yves Adams, taken from article linked above):

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

I was looking over the ideas list recently and noticed that Page had suggested we cover a specific bird way back in 2020! It’s about time we get to it, so thanks to Page we’re going to learn about penguins this week, including a penguin mystery.

But first, we have a birthday shout-out! Happy birthday to EllieHorseLover, whose birthday comes right before next week’s episode comes out. Have a fantastic birthday, Ellie, and I agree with you about horses. They are awesome and so are you.

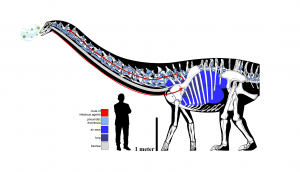

Also, a quick correction from last week’s episode about Dolly the dinosaur. If you listened to episode 264 the day it came out, you heard the incorrect version, but I was able to correct it and upload the new version late that day. Many thanks to Llewelly, who pointed out that Dolly hasn’t actually been identified as a Diplodocus, just as a sauropod in the family Diplodocidae. Paleontologists are still studying the fossil and probably will be for some time. Also, I said that sauropods aren’t related to birds but that’s not the case. Sauropods share a common ancestor with birds and that’s why they both have the same kind of unusual respiratory system.

So, speaking of birds, it’s time to learn about penguins! We’ve talked about penguins twice before, but not recently at all. It’s about time we really dug into the topic.

Penguins live in the southern hemisphere, including Antarctica. The only exception is the Galapagos penguin, which we talked about in episode 99, which lives just north of the equator. Penguins are considered aquatic birds because they’re so well adapted to swimming and they spend most of their time in the ocean finding food. Instead of wings, their front limbs are flippers that they use to maneuver in the water. They’re incredibly streamlined too, with a smooth, dense coat of feathers to help keep them warm in cold water without slowing them down.

One of the ways a penguin keeps from freezing in the bitterly cold winters of Antarctica and in cold water is by a trick of anatomy that most other animals don’t have. The artery that supplies blood to the flippers crosses over the veins that return blood from the flippers deeper into the body. The arterial blood is warm since it’s been through the body’s core, but the blood that has just traveled through the flippers has lost a lot of heat. Because the veins and the arteries cross several times, the cold venal blood is warmed by the warm arterial blood where the blood vessels touch, which means the blood returning into the body’s core is warm enough that it doesn’t chill the body.

Penguins groom their feathers carefully to keep them clean and spread oil over them. The oil and the feathers’ nanostructures keep them from icing over when a penguin gets out of the water in sub-zero temperatures. The feathers are not only super-hydrophobic, meaning they repel water, their structure acts as an anti-adhesive. That means ice can’t stick to the feathers no matter how cold it is. In 2016 researchers created a nanofiber membrane that repels water and ice with the same nanostructures found in penguin feathers. It could eventually be used to ice-proof electrical wires and airplane wings.

Penguin feathers also trap a thin layer of air, which helps the penguin stay buoyant in the water and helps keep its skin warm and dry.

While a penguin is awkward on land, it’s fast and agile in the water. It mostly eats small fish, squid and other cephalopods, krill and other crustaceans, and other small animals, and it can dive deeply to find food. The emperor penguin is the deepest diver, with the deepest recorded dive being over 1,800 feet, or 565 meters. The gentoo penguin has been recorded swimming 22 mph underwater, or 36 km/hour.

Penguins are famous for being mostly black and white, but in 2010, a study of an extinct early penguin revealed that it looked much different. The fossil was found in Peru and is incredibly detailed. The flipper shape is clear, proving that even 36 million years ago penguins were already fully aquatic. Even some of the feathers are preserved, allowing researchers to reconstruct the bird’s coloration from melanosomes in the fossilized feathers. They show that instead of black and white, the extinct penguin was reddish-brown and gray. The bird was also one of the biggest penguins known, up to five feet long, or 1.5 meters.

Another species of extinct penguin was discovered in 2006 in New Zealand by a group of school children on a field trip. The New Zealand penguin lived between about 28 and 34 million years ago and while it wasn’t as big as the Peru fossil penguin, it had longer legs that made it about 4.5 feet tall, or 1.4 meters. It was described as a new species in September of 2021 and somehow I missed that one when I was researching the 2021 discoveries episode.

The smallest penguin alive today is the fairy penguin, which only grows 16 inches tall at most, or 40 cm. It lives off the southern coasts of Australia and Chile, and all around New Zealand’s coasts. It’s also called the little blue penguin because its head is gray-blue. The largest penguin is the emperor penguin, which lives in Antarctica and can grow over four feet tall, or 130 cm.

The king penguin looks like a slightly smaller version of the emperor penguin, which makes sense because they’re closely related. It can stand over 3 feet tall, or 100 cm. Its numbers are in decline due to climate change that has caused some of the small fish and squid the penguins eat to move away from the penguin’s nesting grounds. Large-scale commercial fishing has also reduced the number of fish available to penguins. As a result, the penguins have a hard time finding enough food for themselves and their babies. King penguins are protected, though, and conservation efforts are in place to stop commercial fishing near their nesting grounds. A ban on commercial fishing around Robben Island in South Africa, where the endangered African penguin nests, increased the survival of chicks by 18%, so hopefully the same will be true for the king penguin.

In early 2021, a Belgian wildlife photographer named Yves Adams was leading a group of photographers on an island where king penguins live. They spotted a group of the penguins swimming nearby when Adams noticed that one of the penguins seemed really pale. It was yellowish-white instead of black and white, although it did have the yellow markings on its head and breast that other king penguins have. It and the other penguins came ashore and Adams got lots of pictures of it. Ornithologists who have studied the pictures aren’t sure what kind of genetic anomaly has caused the penguin’s coloration, but with luck scientists will be able to find it again and take a genetic sample.

The king penguin is also the subject of a small penguin mystery, but the mystery starts with the great auk. As we talked about in episode 78, the name penguin was originally used for a bird also called the great auk or gairfowl, which lived in the northern hemisphere. It was common throughout its range until people decided to start killing them by the thousands for their feathers and meat. By 1844, the last pair of great auks were killed. The great auk was a black and white aquatic bird that looked a lot like a penguin due to convergent evolution.

The story goes that in the late 1930s people started seeing great auks on the Lofoten Islands off the coast of Norway. Since this was 70 years after the great auk officially went extinct, the reports caused a flurry of excitement.

While a small, scattered population of great auks probably did persist for years or even decades after their official extinction, once an expedition investigated the Lofoten Islands they discovered not auks but penguins. Specifically, a small group of king penguins. How did the penguins get there from their natural range in various sub-Antarctic islands on the other side of the world?

Some reports say whalers captured some penguins as pets and later released them, but it actually appears that the introduction of nine king penguins to two islands off the coast of Norway was done by the Nature Protection Society, backed by the Norwegian government, in 1936. The penguins were still there until at least 1944, with the last sighting coming from 1954.

These weren’t the only penguins released in the islands. In 1938 the Norwegian government released around 60 other penguins from various species onto the islands. The goal was to establish penguin breeding colonies in Norwegian waters in a confused attempt to claim the Antarctic for Norwegian whaling. The real mystery is why they thought that would work.

Very occasionally, a stray penguin is found in the northern hemisphere with no idea how it got there. In the past, people assumed the penguin got lost and swam the wrong way or got pushed away from its homeland by storms, but these days biologists think these lost penguins were transported by fishing boats. Sometimes a penguin will get tangled in a fishing net and hauled aboard by accident, and the fishers will untangle it and keep it as a pet for a while before setting it free. It would be better if the penguin was set free immediately so it could return to its home, but it’s better than being killed. Just ask the penguin.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. If you like the podcast and want to help us out, leave us a rating and review on Apple Podcasts or Podchaser, or just tell a friend. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us for as little as one dollar a month and get monthly bonus episodes.

Thanks for listening!