Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 11:30 — 13.2MB)

Sign up for our mailing list! We also have t-shirts and mugs with our logo!

Thanks to Zachary for suggesting this topic! Let’s learn about some sightings of what look like miniature theropod dinosaurs running around in the American Southwest!

Further reading:

A collared lizard running (photo by Joe McDonald from this page):

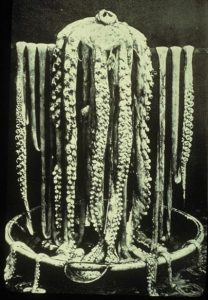

Basilisks running:

A female wild turkey:

A male wild turkey (note the tuft of hair-like feathers sticking forward, called a beard) (picture from this page):

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

Thanks to Zachary for his email a while back that helped shape this episode. Zachary has kept a lot of different kinds of pets, which we had a nice conversation about, and one of the reptiles he’s kept as a pet is in this episode. I’ll reveal which one at the end.

But first, a small correction, maybe. Paul from the awesome podcast Varmints! messaged me to point out that the word spelled A-N-O-L-E is pronounced a-NOLL, not a-NO-lee. I’d looked it up before I recorded so that confused me, so I looked it up again and it turns out that both pronunciations are used in different places and both are correct. So if you’ve always heard it a-NOLL, you’re fine, but now I can’t decide which pronunciation I should use.

This week we’re going to learn about an interesting mystery of the American southwest. Even though non-avian dinosaurs went extinct 66 million years ago, occasionally someone spots what they think is a little dinosaur running along on its hind legs. They’re sometimes called mini rexes.

Many reports come from the American southwest, especially Colorado, Arizona, and Texas. For instance, in the late 1960s two teenaged brothers were looking for arrowheads near their home in Dove Creek, Colorado when they were startled by an animal running away from them at high speed. The boys said it looked like a miniature dinosaur, only about 14 inches tall, or 35 centimeters. It was kicking up so much dust as it ran on its hind legs that the boys had trouble making out details. They did note that it seemed to be brown and possibly had a row of spines running down its back, maybe even two rows of spines, similar to an iguana’s. It had long hind legs and shorter front legs that it held out in front of it as it ran.

The animal left behind three-toed footprints that the boys followed until they disappeared into some brush. The boys were familiar with turkey footprints but these were different, with the toes closer together and no rear-pointing toe prints.

In April 1996, in Cortez, Colorado, a woman saw an animal run past her house on its hind legs, seemingly from a nearby pond. It was greenish-gray and stood about 3.5 feet tall, or about a meter. It had a long neck and long, tapering tail. She didn’t notice its front legs but its hind legs had muscular thighs but were thinner below the hock joint.

One night in July 2001, a woman and her grown daughter were driving near Yellow Jacket, Colorado when they noticed an animal at the edge of the road. At first the driver thought it was a small deer and slammed on the brakes so she wouldn’t hit it, but when it darted across the road both women were shocked to see what looked like a small dinosaur pass through the headlight beams of the car. They reported it was about 3 feet tall, or 91 centimeters, and that it had no feathers or fur. Its legs were thin and long, while its arms were tiny and held out in front of its body. It had a slender neck, a small head, and a long tapering tail.

The witnesses in both the 1996 sighting and the 2001 sighting noted that the animal they saw ran gracefully. They also all agreed that the animals’ skin appeared smooth.

Lots of dinosaurs used to walk on their hind legs, but the reptiles living today are all four-footed. There are a few lizards that run on their hind legs occasionally, though, and one of them lives in the American southwest. The collared lizard, also called the mountain boomer, will run on its hind legs to escape predators. Females are usually light brown while males have a blue-green body and light brown head. The name collared lizard comes from the two black stripes both males and females show around their necks, with a white stripe in between. During breeding season, in early summer, females also have orange spots along their sides.

The collared lizard can run up to 16 miles an hour, or 26 kilometers per hour, for short bursts on its hind legs. It uses its long tail for balance as it runs, and its hind legs are three times the length of its front legs. This makes it a good jumper too. It mostly eats insects but will occasionally eat berries, small snakes, and even other lizards. It hibernates in winter in rock crevices.

While the teenaged boys probably saw a collared lizard in the 1960s, the other two sightings we just covered sound much different. The collared lizard typically only grows up to 14 inches long, or 35 centimeters, including its long tail.

A few other lizards are known to run on their hind legs, such as the basilisk that lives in rainforests of Central and South America. It’s famous for its ability to run across water on its hind legs. It’s much larger than the collared lizard, up to 2.5 feet long, or 76 centimeters, including its long tail. It holds its front legs out to its sides when running on its hind legs, and the toes on its hind feet have flaps of skin that help stop it from sinking. It has a crest on its head, and the male also has crests on his back and tail. It can be brown or green in color.

The basilisk is sometimes kept as an exotic pet. In 1981 in New Kensington, Pennsylvania, four boys playing along some railroad tracks saw a green lizard that they thought was a baby dinosaur. It was 2 feet long, or 61 centimeters, and had a crest and an extremely long tail. It ran away on its hind legs but one of the boys, who was 11 years old, managed to catch it. It startled him by squealing and he dropped it again, and this time it got away. It sounds like an escaped pet basilisk.

But let’s go back to our mini rex sightings from 1996 and 2001, the ones of dinosaur-like animals running gracefully on their hind legs with a long neck and long tail. These don’t sound like lizards at all. When lizards run on their hind legs, they don’t look much like how we imagine a tiny raptor dinosaur would look. They appear awkward while running, with their arms sticking out and their heads pointing more or less upward. While all the lizards known that can run on their hind legs have long tails, they all have relatively short necks.

There’s another type of animal that’s closely related to the dinosaurs, though, and every single one walks on its hind legs. That’s right: birds! All the birds alive today are descended from dinosaurs whose front legs evolved for flight. Even flightless birds are well adapted to walk on two legs.

Let’s look at the details of those two sightings again. Both were of animals estimated as about three feet tall or a little taller, or up to about a meter, with long neck, small head, long tapering tail held above the ground, and long, strong legs that were nevertheless thin. Both also appeared smooth. In one of the sightings, the front legs were tiny and held forward; in the other, the witness didn’t notice the front legs.

My suggestion is that in these two sightings, at least, the witnesses saw a particular kind of bird, a wild turkey. That may sound ridiculous if you’re thinking of a male turkey displaying his feathers, but most of the time turkeys don’t look round and poofy. Most of the time, in fact, the wild turkey’s feathers are sleek and its tail is an ordinary-looking long, skinny bird tail instead of a dramatic fan. Its feathers are mostly brown and black, the upper part of its long neck is bare of feathers, as is its small head, and its legs are long and strong but relatively thin. It also typically stands 3 to 3.5 feet tall, or up to about a meter, although some big males can stand over 4 feet tall, or 1.2 meters. As for the front legs seen by witnesses in 2001, a full-grown male turkey has a tuft of long, hair-like feathers growing from the middle of his breast, called a beard. It sticks out from the rest of the feathers and might look like tiny arms if you were already convinced you were looking at a dinosaur instead of a bird.

That’s not to say that all mini-rex sightings are of turkeys, of course, but some of them probably are. The wild turkey lives throughout much of the United States, including most of Colorado. Since birds are the closest animals we have to dinosaurs these days, though, that’s still pretty neat.

Finally, the reptile Zachary kept as a pet was the collared lizard. I didn’t want to say so at the beginning and potentially spoil part of the mystery for some people!

You can find Strange Animals Podcast at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. If you like the podcast and want to help us out, leave us a rating and review on Apple Podcasts or Podchaser, or just tell a friend. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us for as little as one dollar a month and get monthly bonus episodes.

Thanks for listening!