Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 8:35 — 9.5MB)

Thanks to Lorenzo for suggesting Tiarajudens! We’ll learn about it this week along with another extinct animal, Vintana.

Further reading:

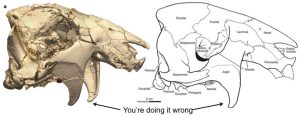

Funky facial flanges [the skull picture below comes from this site]

First Postcranial Fossils of Rare Gondwanatherian Mammal Unearthed in Madagascar

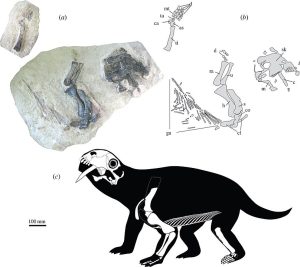

The Earliest Saberteeth Were for Fighting, Not Biting [the skeleton picture below comes from this site]

Vintana’s skull had weird jugal flanges:

Tiarajudens had saber teeth as well as palatal teeth:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

Just last month we had an episode about the tenrec and an extinct animal called Adalatherium. At the end of that episode, I said something I say a lot, that we don’t know very much about it or the other ancient mammals that lived at the time, and that I hoped we would find some new fossils soon. Well, guess what! A paper about a newly discovered Gondwanathere fossil was published just a few days ago as this episode goes live. Rather than save it for the updates episode later this summer, let’s learn about an animal named Vintana sertichi, along with a suggestion from Lorenzo for another extinct animal.

As you may remember from episode 324, Adalatherium is a member of a group of animals called Gondwanatheria, which arose in the southern hemisphere around the time that the supercontinent Gondwana was breaking apart. We only have a few fossils of these animals so paleontologists still don’t know how they’re related, although we do know they’re not related to the mammals living today. Every new specimen found of these rare mammals helps scientists fill the gaps in our knowledge. That’s what happened with Vintana.

Vintana lived at the end of the Cretaceous, until the asteroid strike about 66 million years ago that killed off the non-avian dinosaurs and a whole lot of other animals, probably including Vintana. The first fossilized specimen was a skull found in Madagascar and described in 2014. It was really well preserved, which allowed scientists to learn a lot about the animal.

Vintana was an active animal that ate plants. It had large eyes and a good sense of smell and hearing, so its ears might have been fairly large too. Its face probably looked a lot like a big rodent’s face, but the skull itself had a weird feature. The cheekbones extended downward on each side next to the jaw, and these extensions are called jugal flanges. They would have allowed for the attachment of really big jaw muscles. That suggests that Vintana could probably give you a nasty bite, not that you need to worry about that unless you find a time machine. It might also mean that Vintana ate tough plants that required a lot of chewing.

Vintana probably looked a lot like a groundhog, or marmot, which we talked about recently in episode 327. It wasn’t related to the groundhog, though, and was bigger too. Scientists estimate it weighed about 20 lbs, or 9 kg.

The fossil specimen of Adalatherium that we talked about in episode 324 was discovered in Madagascar in 2020. When a tail vertebra from another mammal was found in the same area, researchers scanned and compared it to Adalatherium’s vertebrae. They were similar but not an exact match, plus the new bone was almost twice as large as the same bone in Adalatherium’s spine. It matched the size of Vintana and was assigned to that species. Vintana was probably related to Adalatherium but was bigger and had a shorter, wider tail. And as of right now, that’s just about all we know about it.

Next, let’s learn about another extinct animal, this one suggested by Lorenzo. Lorenzo gave me a bunch of great suggestions and I picked this one to pair with Vintana, because otherwise this episode would have been really short. Vintana lived at the end of the dinosaurs, but Tiarajudens lived long before the dinosaurs evolved, around 260 million years ago.

Tiarajudens was a therapsid, a group that eventually gave rise to mammals although it’s not a direct ancestor of mammals. Technically it’s an anomodont. We don’t have a complete skeleton so we don’t know for sure how big it was, but we do have a skull and some leg bones so we know it was about the same size or a little bigger than a big dog. There are only two species known, one from what is now South America and one from what is now Africa, but 260 million years ago those two landmasses were connected and were part of the supercontinent Gondwana.

Tiarajudens had weird teeth even compared to other anomodonts. It had a pair of saber teeth that resembled the tusks found in later anomodonts, but they weren’t really tusks. They were big fangs that grew from the upper jaw and jutted down out of the mouth well past the bottom of the jaw. Later anomodonts probably used their tusks to dig up plants, but there aren’t wear marks on Tiarajudens’s saber teeth that would indicate it used them for digging. Many paleontologists think it used them for defense and to fight other Tiarajudenses over mates or territory. We don’t know if the saber teeth were present in all individuals, since we’ve only found a few specimens.

Tiarajudens also had palatal teeth. These days palatal teeth are mostly found in amphibians, especially frogs. Palatal teeth grow down from the roof of the mouth and Tiarajudens’s were flat like molars. We haven’t found a lower jaw yet so we don’t know what the bottom teeth looked like, but from the wear marks on the upper teeth, it was clear that Tiarajudens was actually chewing its food. That was really unusual among all animals at the time, and in fact Tiarajudens is one of the first animals to really chew its food instead of giving it a chomp or two and swallowing it mostly whole. It ate plants, probably tough ones that required a lot of chewing.

So what did Tiarajudens look like beyond its teeth? It probably resembled a bulky four-legged dinosaur with a short tail, but it may have had whiskers. That’s as much as we know right now, because Tiarajudens was not only an early therapsid, it was different in many ways from most other therapsids known. For instance, it had what are called gastralia, or belly ribs, which were once common in tetrapods. Some dinosaurs had gastralia, including T. rex, but most therapsids didn’t. These days crocodiles and their relations still have gastralia, and so does the tuatara, but most animals don’t.

Both Tiarajudens and Vintana were unusual animals that we just don’t know much about. Let’s hope that changes soon and scientists find more fossils of both. I’ll keep you updated.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. If you like the podcast and want to help us out, leave us a rating and review on Apple Podcasts or Podchaser, or just tell a friend. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us for as little as one dollar a month and get monthly bonus episodes.

Thanks for listening!