Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 14:44 — 11.8MB)

This week we’re going to learn about animals with TENTACLES ON THEIR FACES oh my gosh

Thanks to Llewelly for the topic suggestion!

Don’t forget to come see me on the panel How to Start Your Own Indie Podcast at DragonCon 2018, at 4pm on Sunday, September 2, 2018 in the Hilton Galleria 6.

A tentacled snake:

A star-nosed mole. Hello, nose star!

A caecilian, with its tiny tentacle circled:

A squidworm:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

I’m back from Paris this week and definitely jet-lagged, but this episode should wake everyone up. It’s about animals with TENTACLES ON THEIR FACES

A big thanks to Llewelly who sent me an article about the tentacled snake, which turned into this episode. I love it when people send me links to articles or suggestions for topics. I have a bunch of suggestions I haven’t gotten to yet, but I promise I will as soon as possible. I’m like a dog in a park full of squirrels. There are so many exciting animals to chase, it’s hard to know which one to follow.

That reminds me. If you go to the strangeanimalspodcast.com website, there’s a page with a list of animals that I’ve covered in various episodes. If you don’t see your favorite animal on that list, feel free to email me with your suggestion!

Also, if you’re listening to this episode the week it comes out, this coming weekend I’ll be at DragonCon in Atlanta. If you’re going to be there too, I’m on a panel about how to start your own podcast, part of the podcasting track. It’ll be at 4pm on Sunday in the Hilton Galleria 6.

Now, on to the tentacles.

We’ll start with the tentacled snake, which lives in parts of southeast Asia. It lives in both fresh and ocean water and doesn’t come on land very often. When it does, it has trouble getting around since it’s adapted for swimming. It grows up to three feet long, or about 90 cm, and is brown or gray, sometimes with stripes, sometimes with blotches. Its body and head are flattened and its scales are rough. Basically it looks a lot like an old stick with lichen on it. If something disturbs it, it holds its body completely rigid even if it’s lifted out of the water, which makes it look even more like a stick.

Its nose is squared-off with nostrils at the top so it can more easily grab breaths at the water’s surface. And it has a pair of short tentacles at the corners of its snout that it uses to help it sense the fish and frogs it eats. It has weak venom, but its fangs are in the back of its mouth and not dangerous to humans.

It likes slow-moving water, murky water, or water with a lot of vegetation in it because it doesn’t rely on its eyes to sense fish, although it has good eyesight. The tentacles are finely attuned to movement in the water and the snake can sense when a fish is approaching even if it can’t see the fish.

The tentacled snake is an ambush predator. It uses its tail to anchor itself in the water, and holds its body in a J shape, either head down or head up. When a fish swims nearby, the snake moves the looped section of its body extremely quickly without moving its head, which creates a pressure wave in the water that makes the fish think there’s a predator approaching. The fish doubles back and tries to flee, but in the wrong direction—basically right into the snake’s face.

Another animal with tentacles on its face is the star-nosed mole. It’s a mammal that lives in parts of northeastern North America, especially in marshy areas. Like other moles, it’s not very big, only about six inches long, or 15 cm. Its fur is dense and velvety, it has tiny eyes and ears that are mostly hidden under its fur, and its tail is short. It spends a lot of time in the water but it also digs shallow tunnels. It eats worms, insects, mollusks, and small animals of various kinds, including frogs.

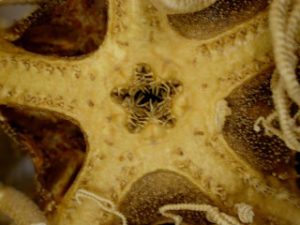

The star-nosed mole has eyes, but they’re tiny and don’t function very well. Instead, it senses prey and navigates using the unique structure at the tip of its snout: 22 tiny tentacles containing over 25,000 sensory receptors. The structure is roughly star-shaped so is usually called a nose star. It actually is more starfish-shaped, if you ask me, like it has a tiny pink starfish growing out of the tip of its nose, with two little nostrils in the middle.

Mammals are not known for their tentacles. The star-nosed mole is the only mammal with tentacles, in fact—at least as far as I can find out. And the star-nosed mole has tons of weird adaptations as a result. The tentacles of its nose star are the most sensitive organ of touch in any mammal. Think about how sensitive your fingertips are and how much information you can learn from just touching something with a fingertip. The star-nosed mole’s star has five times the number of nerve fibers than your entire hand contains, and the star is smaller than your pinky fingernail. It’s so sensitive and the mole can gain so much information from it that researchers compare it more to a sense of sight than of touch. The mole’s nervous system is also extremely efficient in order to process all the information coming from the star, literally just about at the physiological limit of neurons. That means the star-nosed mole can identify prey and decide whether to eat it in only 8 milliseconds.

You know how long it takes you to blink your eyes? About 350 milliseconds. A star-nosed mole could have examined and made eating decisions about 44 things in that same time. And since it can also eat most small prey like bugs in only 200 milliseconds, it could have also eaten one and a half things in the time you blink your eyes. This is blowing my mind, everyone, especially since I am the slowest eater in the world.

You know what else the star-nosed mole can do? It can smell underwater. It blows tiny bubbles into the water and breathes them back in to examine them for scents. The tentacles of the mole’s star keep the bubbles from floating away before the mole can breathe them back in. The star-nosed mole is a good swimmer and the tunnels it digs often start and end underwater. Researchers think that hunting underwater and in swampy soil helps keep the mole’s sensitive nose star from damage. If you rub your fingertips lightly over sandpaper or a brick’s surface, after only a few seconds you’ll feel some discomfort, but soft mud doesn’t hurt fingertips or nose stars.

Another animal with face tentacles is the caecilian. Caecilians are legless amphibians that look like worms or snakes, but are more closely related to frogs and salamanders. Probably. We don’t know a lot about how caecilians developed, and some researchers think they may actually be more closely related to reptiles than amphibians.

The longest caecilian, Thompson’s caecilian, grows to some five feet long, or 1.5 meters. It lives in Colombia in South America and is gray or black. The smallest species only grow to about four inches long, or 10 cm. There are some 180 species of caecilian that we know of, which live in tropical regions in many parts of the world. Many dig burrows and spend most of their time underground, while some live in the water. Most eat small animals like worms and insects. Even though all caecilians are long, unlike worms and snakes, most don’t actually have a tail, or may only have a short tail. It’s just hard to tell because they also don’t have legs. Some species appear snakey while some have what look like body segments like an earthworm, which helps it wriggle its way through soil like a worm. It even moves in what’s called an accordion-type fashion like a worm where it bunches up parts of its body and stretches other parts out to advance.

The caecilian has a pair of tiny tentacles between its eyes and nostrils that grow out of an opening in the snout. The tentacles appear to have developed from the tear duct and eye muscles. Some caecilian species have tiny eyes, although they may be hard to see. Some species have no eyes at all. Some species have eyes, but they’re actually beneath the skull bones. In two species from Africa, the eyes are under the skull but are connected to the tentacles, and the caecilian can extend its tentacles and actually move its eyes out of the skull and into the tentacle. The tentacle tips lack pigment so light can pass through. You see what’s going on here? EYE STALKS. Eye stalks aside, researchers think that the tentacles mostly contain chemical receptors that the caecilian uses to find prey.

Caecilians are really interesting animals. Different species are sometimes radically different from each other in very basic ways. For instance, how babies develop. Some caecilian species lay eggs that hatch into larvae, like tadpoles. Some lay eggs that hatch into miniature caecilians, like certain species of frog whose eggs hatch into tiny frogs instead of tadpoles. Three caecilian species give birth to up to four live babies that are already developed, and those babies grow within the mother by eating a special oviduct lining of her body, which they scrape off with teeth modified for this purpose. Two egg-laying species have a similar process for feeding babies, but in this case the mother caecilian develops a thickened skin that’s full of nutrients, which her babies scrape off with modified teeth. It doesn’t hurt the mother, who grows more of the skin as the babies eat it.

One species of caecilian doesn’t even have lungs, Atretochoana eiselti. Some salamanders don’t have lungs either, and instead absorb oxygen through the skin. But salamanders that breathe this way are either very small or live in cold, fast-flowing water with high oxygen content. Atretochoana grows nearly three feet long, or 80 cm, but seems to prefer warmer, slower water. So researchers aren’t sure how it breathes. Not a lot is known about it in general, but it does have muscles that attach to the skull that aren’t found in any other organism studied. Its head is broad and flat. We don’t even know what it eats.

The caecilian has two sets of jaw muscles, if you were wondering. Researchers aren’t sure why, but they suspect it has something to do with keeping the head and neck rigid while the caecilian pushes its way through the soil. Some caecilians are toxic, and since many species are brightly colored, it’s a good bet that those species probably contain at least some toxins. But again, we don’t know for sure because there haven’t been very many studies on caecilians.

There are other animals with tentacles on their faces, but those are the big three that are alive today. Catfish whiskers, properly called barbels, aren’t technically tentacles, and I have a whole episode on catfish planned eventually so I’ll skip them this time. Snails and slugs have four head appendages that are tentacle-like, two of them eyestalks and the other pair for smell and touch. Back in the Cambrian, the eel-like Pikaia gracilens had a pair of long tentacles on its head and rows of shorter bristles along the sides of its head that may have acted as gills. Some species of modern lancelet look very similar to Pikaia and even have similar sensory appendages, but these are more similar to cilia than actual tentacles.

But another living animal, a deep-sea polychaete worm called the squidworm, has actual tentacles on its head—ten of them. It grows around 4 inches long, or 10 cm, not counting its tentacles, which are as long or longer than the body. It lives in the depths up to 2800 meters down, or almost 1.75 miles below the ocean’s surface. Two of its tentacles are yellowish and usually held in a curled-up position, and those are the ones the worm uses to collect food—probably plankton and detritus that sinks from the upper ocean. The other tentacles are used for breathing, and it also has feathery sensory organs growing from its head.

But the awesome thing is, the squidworm was only discovered in 2007 off the coast of the Philippines. And it’s not rare. In fact, it seems to be really common, which means there are probably other species of squidworm that haven’t been discovered yet. And there might be other tentacled things down there too, who knows?

You can find Strange Animals Podcast online at strangeanimalspodcast.com. We’re on Twitter at strangebeasties and have a facebook page at facebook.com/strangeanimalspodcast. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. If you like the podcast and want to help us out, leave us a rating and review on Apple Podcasts or whatever platform you listen on. We also have a Patreon if you’d like to support us that way.

Thanks for listening!