Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 20:41 — 21.0MB)

In honor of my new favorite band, The Hu, let’s learn about some animals from their country, Mongolia! (You can also watch the “Wolf Totem” video with English lyrics.)

The Hu. Oh my heart:

If you need the podcast’s feed URL, it’s https://strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net/feed/podcast/

A handsome prize-winning domesticated yak and rider (photo taken from this site):

The saiga, an antelope with a serious snoot:

A Bactrian camel (photo by *squints* Brent Huffman, looks like):

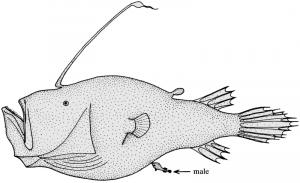

The taimen, a fish that would swallow you whole if it could:

Further watching:

A clip from the TV show Beast Man showing how moist the soil is in parts of the Gobi

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

Recently, podcaster Moxie recommended a band she liked on her excellent podcast Your Brain on Facts. The band is called The Hu, spelled H-U, and she mentioned they were from Mongolia. I checked the band out and FELL IN LOVE WITH THEM OH MY GOSH, so not only have I been recommending them to everyone, I also want to learn more about their country. So let’s learn about some interesting animals from Mongolia.

But first, a quick note. About six months ago I had to migrate the site to an actual podcasting host, since I’d run out of memory on my own site. Well, there doesn’t seem to be any point to keep the old site open anymore since all the podcasting apps I checked appear to have the new feed and everything is on the new website. So in another week or two, the old site will close. If you suddenly stop receiving new episodes, please email me at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com and let me know what app you use for podcast listening, so I can get it updated. In the meantime, if your app gives you the option of entering a podcast feed manually, I’ve made a new page on the website, strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net, where you can copy and paste the feed URL. It’s also in the show notes. Feel free to contact me if you have any questions or if something isn’t working. Now, back to Mongolia and its animals.

Mongolia is located in Asia, north of China and south of Russia, with the Gobi Desert to the south and various mountain ranges to the north and west. You actually probably know some Mongolian history without realizing it. You’ve heard of the Great Wall of China, right? Well, it was built to keep out the Mongols, who would ride their horses into China and raid villages. Genghis Khan was the most famous Mongol in history, a fearsome warrior who conquered most of Eurasia in the early 13th century.

While you’re thinking about that, here’s a short clip of my favorite Hu song, called “Wolf Totem.” There’s a link in the show notes if you want to watch the official video.

Oh my gosh I love that song.

Anyway, Mongolia has short summers but long, bitterly cold winters. Many people are still nomadic, a traditional culture that’s horse-based. A lot of Mongolia is grassland referred to as the steppes, which isn’t very good for farming, but which is great for horses. Domesticated animals include horses, goats, and a bovid called the yak. Let’s start with that one.

The yak is closely related to both domestic cattle and to bison, and is a common domesticated animal in much of Asia. The wild yak is native to the Himalaya Mountains in Eurasia. It’s a different species from the domesticated yak and is larger, with a big bull wild yak standing up to 7.2 feet at the shoulder, or 2.2 meters. A big bull domesticated yak is closer to 4 ½ feet high at the shoulder, or almost 1.4 meters. The wild yak is usually black or brown, but domesticated yaks may be other colors and have white markings. Occasionally a wild yak is born that has golden fur.

Both male and female yaks have horns, although the males usually have larger horns with a broader spread than the females. The male also has a larger shoulder hump than the female, much like bison, and males are also larger and heavier. The reason the domesticated yak is so popular in the mountains and in areas where winters are long and cold, like Mongolia, is that it has long, dense hair with a soft undercoat that keeps it warm. It’s also naturally adapted to high altitudes where there’s less oxygen, with large lungs and heart. As a result, it doesn’t do well in lower altitudes and can even die of heat if it gets too warm, since it can’t sweat.

The yak is domesticated for its meat and milk, to pull plows, as a riding animal, and for its soft undercoat which is combed out in spring and used to make yarn. Even the yak’s droppings are useful, since they’re mostly undigested plant fibers that burn really well once they’re dry, so they can be used instead of wood to build fires.

In Mongolia, yak milk is used to make butter, cheese, and yogurt. And vodka. Yak races and yak festivals are increasingly popular as tourist attractions, but yak herding is a tradition dating back thousands of years.

The wild yak is a protected species where it still lives, mostly in China, India, and Tibet, but it’s still threatened by poaching and habitat loss due to domesticated yak herds pushing out their wild cousins. In the wild, the yak prefers to live in elevations too high for trees to grow. It eats grass and other plant material and can survive on a diet too poor to sustain cattle. This is because it has a larger rumen and the plants it eats can stay in its digestive tract for longer to extract as many nutrients as possible.

It’s rare for a domesticated animal to also be endangered, but yak herding in Mongolia is in steep decline, with 70% fewer yaks raised now than there were twenty years ago. There are a number of reasons for the decline. More people are moving to cities in Mongolia since they can make more money there instead of farming. Some farmers have started raising cattle or yak-cattle hybrids instead of yaks, since cattle and cattle hybrids produce more milk and meat even though they eat considerably more than yaks do. Worse, cloth made of sheep’s wool and other fibers is being exported by Chinese farmers labeled as Mongolian yak wool, which has caused the market for actual yak wool to crash. Yak wool is as soft and warm as cashmere, which comes from goats, but yaks are much better for the fragile mountain environment in Mongolia than goats are. Hopefully, increased tourism, including yak festivals, will help farmers make money from their traditional ways of life.

Instead of mooing like a cow, the yak grunts, although wild yak are usually silent. This is what a domesticated yak sounds like:

[yak grunting]

Another bovid, this one found only in Mongolia, is the Mongolian saiga. Some researchers consider it a subspecies of the saiga that was once found throughout Eurasia while others consider it a separate species. It’s critically endangered, possibly with as few as 5,000 animals left in the wild, threatened by poaching and competition with livestock. But the saiga frequently has twins instead of just one baby at a time, which helps its numbers increase quickly as long as people stop shooting the males for their horns. Some people think have medicinal qualities. They don’t, of course. The saiga almost went extinct back in the 1920s, but it recovered, so it can recover again as long as people leave it alone.

The saiga stands nearly three feet tall at the shoulder, or 81 cm, and its coat is usually a sandy pale brown in color. In winter it grows a long coat to keep warm. It’s also rather stocky in shape compared to other antelopes, which helps keep it warm too. But the main adaptation it has for cold weather is its nose. The saiga has a remarkable snoot. It almost looks like it has a little trunk. Its muzzle is considerably enlarged to make plenty of room for large nasal passages, which warms air before it reaches the lungs and also filters dust from the air. The nostrils point downward. The males have pale-colored horns that can grow nearly nine inches long, or 22 cm, although the closely related Russian saiga has horns that are almost twice that long. The horns grow upward and slightly back. The saiga migrates across the steppes and lives in herds that are sometimes quite large.

Another animal that’s domesticated but still lives wild in some parts of southern Mongolia and northern China is the Bactrian camel. That’s the camel that has two humps instead of just one. Like the yak, the domesticated and wild Bactrian camels are different species although they’re closely related. The wild Bactrian camel is smaller with a flatter head. A domesticated Bactrian camel can stand up to 7 ½ feet high at the shoulder, or 2.3 meters.

The wild Bactrian camel is critically endangered due to poaching and habitat loss, although it’s protected in both Mongolia and China. There may be only 1,000 of them left in the wild, and some of those are hybrids of wild and feral domesticated Bactrian camels. Since they’re different species, offspring of wild and domesticated Bactrian camels are often infertile. A wild Bactrian captive breeding program in Mongolia is underway and has been successful so far.

When you think of a camel, you probably think of a hot desert. Camels of all kinds are well adapted to desert life. The one-hump camel is a dromedary, which is a domesticated animal native to the Sahara Desert in northern Africa and other arid regions. But the two-humped Bactrian camel is adapted to a different kind of desert, the cold desert. Although it can get hot in the Gobi Desert in summer, winters are long and very cold, but mainly a desert just doesn’t get much rain. In the case of the Gobi, what little moisture it receives in winter is mainly from snow and frost, although it also gets an average of almost 8 inches of rain in the summer, or 19 cm.

The wild Bactrian camel, therefore, has to be able to survive without a lot of water. Some people think camels store water in their humps, but the humps are actually made up of fat. Fat is full of water, though, and when the camel can’t find any food or water, its body will reabsorb the fat to keep itself alive. If you see a camel with floppy or skinny humps, you know it’s not had much to eat recently and has had to use up its fat stores.

The wild Bactrian camel grows thick fur in winter to keep it warm in temperatures that can drop to -27 degrees Fahrenheit in winter, or -32.8 Celsius, but it sheds a lot of this heavy coat in summer when temperatures can soar to 99 F, or 37 C. Unlike most animals, it can safely eat snow without risking hypothermia, where the body core temperature falls to dangerous levels. It can also safely drink water that’s even saltier than the ocean. It lives in small herds that travel across the desert from one water source to another, since if it stayed in one area it would soon eat all the food available. It eats any plants it can find.

Mongolia has several rivers and lakes, so naturally it has some interesting water animals too. The taimen [TIE-min] is a large fish sometimes called the Eurasian river trout or Siberian giant trout, but it’s actually more closely related to the salmon. It lives in parts of Mongolia and Russia but is threatened by overfishing and water pollution. Until recently in Mongolia, people didn’t eat much fish, plus the taimen was considered the offspring of an ancient river spirit so was left alone. These days, unfortunately, not only are more people eating fish in Mongolia, sport fishing has become a big tourist draw. Conservationists are encouraging anglers to practice catch and release to save the remaining population.

The taimen grows up to six feet long, or two meters, and is a vicious predator. It will eat anything it can catch, including smaller taimen, and in fact will occasionally try to swallow a fish that’s too big, and will suffocate and die as a result. It lives in swift-moving water but is sometimes found in lakes. It grows slowly and lives a long time, and there are rumors of it hunting in packs. As a result, it’s sometimes called the river wolf. Stay away from anything called the river wolf, that’s my advice.

It wouldn’t be an episode about Mongolian animals if we didn’t talk about a mystery animal called the Mongolian death worm. We talked about it once before way back in episode ten, about electric animals, but that was a long time ago so let’s look at it again now.

The story goes that a huge wormlike creature lives in the western or southern Gobi Desert, and most of the time it stays below ground. During the rains of June and July it sometimes comes to the surface. It’s generally described as looking like a sausage or an intestine, red or reddish in color, as thick as a person’s arm, and as long as three or four feet, or up to about 1.5 meters. Its head and tail look alike, sort of like a giant fat earthworm, although some reports say it has some pointy bristles or spines at one end. Touching a death worm is supposed to lead to a quick, painful death, because why would you name something a death worm if it didn’t kill you? Some people report that it can even spit venom or emit an electrical shock that can kill people or animals at a distance.

The National Geographic Channel has a show called Beast Man, or used to, I don’t know, but in 2018 it aired an episode about the Mongolian death worm. I didn’t watch the whole episode, just clips, and while they didn’t actually find one, it was interesting. One lady they interviewed, who saw a death worm when she was a little girl, said it was about two feet long, or 60 cm, reddish in color, and its head and tail looked the same. This matches up with what other people have reported. In one clip, the show’s host tests the soil moisture content in the southern Gobi and is surprised that underneath the dry surface, the ground is actually quite moist. I’ll put a link to that one in the show notes.

There are actually earthworms that live in parts of the Gobi, including two species described in 2013. The earthworms don’t resemble reports of the Mongolian death worm, but if an earthworm can survive, other soft-bodied creatures can too. That’s assuming that the death worm is actually a worm and not a reptile or amphibian of some kind.

The best suggestion for what the death worm might be is an animal called the amphisbaenian. It’s sometimes also called the worm lizard, and while it’s not any kind of lizard, it is a reptile. Amphisbaenians live in many parts of the world, including most of South America and parts of North America, parts of Africa, southern Europe, and the Middle East. But since amphisbaenians live almost all of their lives underground, it’s very likely that species unknown to science live in other places. And much of Mongolia is extremely remote and probably not very well explored by scientists.

Amphisbaenians resemble snakes but they also resemble worms. The eyes are tiny and can be hard to spot, and the head and tail look very similar as a result. Many species are pink or reddish in color, although some are blue or other colors, including spotted, and many have scales that grow in a ringed pattern that make it look even more like an earthworm. But they’re not big animals, generally around six inches long, or 15 cm. Also, they’re slender like an earthworm, not as big around as someone’s arm. And they’re completely harmless to humans and large animals.

That doesn’t mean there can’t be a big amphisbaenian living in the remote parts of the Gobi, rarely seen even by the people who live there. Or, of course, the Mongolian death worm might be a completely different kind of animal, one totally unknown to science—maybe one that’s related to the amphisbaenian but radically different in appearance. Or it might be a mythical monster, although there are enough plausible-sounding witness sightings to think there’s something in the Gobi that looks like a big fat red horrible worm, even if it’s not actually dangerous.

What worries me, though, is that there don’t seem to be any sightings from recent times. Only old people report having seen a death worm back when they were young. Considering that so many Mongolian animals are endangered, it could be that the death worm is also declining in numbers so that fewer of them are around to be seen. Let’s hope Mongolian scientists are out there looking for the death worm and that they figure out what it is so it can be protected and studied in its natural habitat.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast online at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. We also have a Patreon at Patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us and get twice-monthly bonus episodes.

Thanks for listening!