Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 14:34 — 16.8MB)

Thanks to Zachary, Enzo, and Oran for their suggestions this week! Let’s learn about some interesting reptiles!

Happy birthday to Vale! Have a fantastic birthday!!

The magnificent Gila monster:

The Gila monster’s tongue is forked, but not like a snake’s:

The remarkable green basilisk (photo by Ryan Chermel, found at this site):

A striped basilisk has a racing stripe:

I took this photo of a basilisk myself! That’s why it’s a terrible photo! The basilisk is sitting on a branch just above the water, its long tail hanging down:

The desert sand boa:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

This week we’re going to learn about three weird and interesting reptiles, with suggestions from Zachary, Enzo, and Oran, including a possible solution to a mystery animal we’ve talked about before!

But first, we have a birthday shoutout! A very happy birthday to Vale! You should probably get anything you want on your birthday, you know? Want a puppy? Sure, it’s your birthday! Want 12 puppies? Okay, birthday! Want to take your 12 puppies on a roadtrip in a fancy racecar? Birthday!

Our first suggestion is from Enzo and Zachary, who both wrote me at different times suggesting an episode about the Gila monster. How I haven’t already covered an animal that has monster right there in its name, I just don’t know.

The Gila monster is a lizard that lives in parts of southwestern North America, in both the United States and Mexico. It can grow up to two feet long, or 60 cm, including its tail. It’s a chonky, slow-moving lizard with osteoderms embedded in its skin that look like little pearls. Only its belly doesn’t have osteoderms. This gives it a beaded appearance, and in fact the four other species in its genus are called beaded lizards. Its tongue is dark blue-black and forks at the tip, but not like a snake’s tongue. It’s more like a long lizard tongue that’s divided at the very end.

The Gila monster varies in color with an attractive pattern of light-colored blotches on a darker background. The background color is dark brown or black, while the lighter color varies from individual to individual, from pink to yellow to orange to red. You may remember what it means when an animal has bright markings that make it stand out. It warns other animals away. That’s right: the Gila monster is venomous!

The Gila monster has modified salivary glands in its lower jaw that contain toxins. Its lower teeth have grooves, and when the lizard needs to inject venom, the venom flows upward through the grooves by capillary force. Since it mostly eats eggs and small animals, scientists think it only uses its venom as a defense. Its venom is surprisingly toxic, although its bite isn’t deadly to healthy adult humans. It is incredibly painful, though. Some people think the Gila monster can spit venom like some species of cobra can, but while this isn’t the case, one thing the Gila monster does do is bite and hold on. It can be really hard to get it to let go.

The fossilized remains of a Gila monster relative were discovered in 2007 in Germany, dating to 47 million years ago. The fossils are well preserved and the lizard’s teeth already show evidence of venom canals. The Gila monster is related to monitor lizards, although not closely, and for a long time people thought it was almost the only venomous reptile in the world. These days we know that a whole lot of lizards produce venom, including the Komodo dragon, which is a type of huge monitor lizard.

In 2005, a drug based on a protein found in Gila monster venom was approved for use in humans. It helps manage type 2 diabetes, and while the drug itself is synthetic and not an exact match for the toxin protein, if researchers hadn’t started by studying the toxin, they wouldn’t have come up with the drug.

The Gila monster lives in dry areas with lots of brush and rocks where it can hide. It spends most of its time in a burrow or rock shelter where it’s cooler and the air is relatively moist, and only comes out when it’s hungry or after rain. It eats small animals of various kinds, including insects, frogs, small snakes, mice, and birds, and it will also eat carrion. It especially likes eggs and isn’t picky if the eggs are from birds, snakes, tortoises, or other reptiles. It has a keen sense of smell that helps it find food. During spring and early summer, males wrestle each other to compete for the attention of females. The female lays her eggs in a shallow hole and covers them over with dirt, and the warmth of the sun incubates them.

The Gila monster is increasingly threatened by habitat loss. Moving a Gila monster from a yard or pasture and taking it somewhere else actually doesn’t do any good, because the lizard will just make its way back to its original territory. This is hard on the lizard, because it requires a lot of energy and exposes it to predators and other dangers like cars. It’s better to let it stay where it is. It eats animals like mice and snakes that you probably would rather not have in your yard anyway, and as long as you don’t bother it, it won’t bother you. Also, it’s really pretty.

Next, Oran wants to learn more about the basilisk lizard. We talked about it very briefly in episode 252 and I actually saw two of them in Belize, so they definitely deserve more attention.

The basilisk lives in rainforests from southern Mexico to northern South America. There are four species, and a big male can grow up to three feet long, or 92 cm, including his long tail. The basilisk’s tail is extremely long, in fact—up to 70% of its total length.

Both male and female basilisks have a crest on the back of the head. The male also has a serrated crest on his back and another on his tail that make him look a little bit like a tiny Dimetrodon.

The basilisk is famous for its ability to run across water on its hind legs. The toes on its large hind feet have fringes of skin that give the foot more surface area and trap air bubbles, which is important since its feet plunge down into the water almost as deep as the leg is long. Without the air trapped under its toe fringes, it wouldn’t be running, it would be swimming. It can run about 5 feet per second, or 1.5 meters per second, for about three seconds, depending on its weight. It uses its long tail for balance while it runs.

When a predator chases a basilisk, it rears up on its hind legs and runs toward the nearest water, and when it comes to the water it just keeps on running. The larger and heavier the basilisk is, the sooner it will sink, but it’s also a very good swimmer. If it’s still being pursued in the water, it will swim to the nearest tree and climb it, because it also happens to be a really good climber.

The basilisk can also close its nostrils to keep water and sand out, which is useful because it sometimes burrows into sand to hide. It can also stay underwater for as long as 20 minutes, according to some reports. It will eat pretty much anything it can find, including insects, eggs, small animals like fish and snakes, and plant material, including flowers. It mostly eats insects, though.

Fossil remains of a lizard discovered in Wyoming in 2015 may be an ancestor to modern basilisks. It lived 48 million years ago and probably spent most of its time in trees. It had a bony ridge over its eyes that shaded its eyes from the sun and also made it look angry all the time. It grew about two feet long, or 61 cm., and may have already developed the ability to run on its hind legs. We don’t know if it could run on water, though.

Finally, Zachary also suggested the sand boa. Sand boas are non-venomous snakes that are mostly nocturnal. During the day the sand boa burrows deep enough into sand and dirt that it reaches a cool, relatively moist place to rest. At night it comes out and hunts small animals like rodents. If it feels threatened, it will dig its way into loose soil to hide. It’s a constrictor snake like its giant cousin Boa constrictor, but it’s much smaller and isn’t aggressive toward humans.

Zachary thinks that the sand boa might actually be the animal behind sightings of the Mongolian death worm. We’ve talked about the Mongolian death worm in a few episodes, most recently in episode 156.

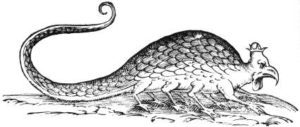

The Mongolian death worm was first mentioned in English in a 1926 book about paleontology, but it’s been a legend in Mongolia for a long time. It’s supposed to look like a giant sausage or a cow’s intestine, reddish in color and said to be up to 5 feet long, or 1.5 meters. It mostly lives underground in the western or southern Gobi Desert, but in June and July it surfaces after rain. Anyone who touches the worm is supposed to die painfully, although no one’s sure how exactly it kills people. Some suggestions are that it emits an electric shock or that it spits venom.

Mongolia is in central Asia and is a huge but sparsely populated country. At least one species of sand boa lives in Mongolia, although it’s rare. This is Eryx miliaris, the desert sand boa. Females can grow up to 4 feet long, or 1.2 meters, while males are usually less than half that length. Until recently it was thought to be two separate species, and sometimes you’ll see it called E. tataricus, but that’s now an invalid name.

The desert sand boa is a strong, thick snake with a blunt tail and a head that’s similarly blunt. In other words, like the Mongolian death worm it can be hard to tell at a glance which end is which. Its eyes are small and not very noticeable, just like the death worm. It’s mostly brown in color with some darker and lighter markings, although its pattern can be quite variable. Some individuals have rusty red markings on the neck.

It prefers dry grasslands and will hide in rodent burrows. When it feels threatened, it will coil its tail up and may pretend to bite, but like other sand boas it’s not venomous and is harmless to humans.

At first glance, the desert sand boa doesn’t seem like a very good match with the Mongolian death worm. But in 1983, a group of scientists went searching for the death worm in the Gobi. They were led by a Bulgarian zoologist named Yuri Konstantinovich Gorelov, who had been the primary caretaker of a nature preserve in Mongolia for decades and was familiar with the local animals. The group visited an old herder who had once killed a death worm, and in one of those weird coincidences, while they were talking to the herder, two boys rushed in to say they’d seen a death worm on a nearby hill.

Naturally, Gorelov hurried to the top of the hill, where he found a rodent burrow. Remember that this guy knew every animal that lived in the area, so he had a good idea of what he’d find in the burrow. He stuck his hand into it, which made the boys run off in terror, and pulled out a good-sized sand boa. He draped it around his neck and sauntered back to show it to the old herder, who said that yes, this was exactly the same kind of animal he’d killed years before.

That doesn’t mean every sighting of a death worm is necessarily a sand boa. I know I’ve said this a million times, but people see what they expect to see. The death worm is a creature of folklore, whether or not it’s based on a real animal. If you hear the story of a dangerous animal that looks like a big reddish worm with no eyes and a head and tail that are hard to distinguish, and you then see a big snake with reddish markings, tiny eyes, and a head and tail that are hard to distinguish, naturally you’ll assume it’s a death worm.

At least some sightings of the death worm are actually sightings of a sand boa. But some death worm sightings might be due to a different type of snake or lizard, or some other animal—maybe even something completely new to science. That’s why it’s important to keep an open mind, even if you’re pretty sure the animal in question is a sand boa. Also, maybe don’t put your bare hand in a rodent burrow.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. If you like the podcast and want to help us out, leave us a rating and review on Apple Podcasts or Podchaser, or just tell a friend. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us for as little as one dollar a month and get monthly bonus episodes.

Thanks for listening!