Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 19:31 — 19.7MB)

Subscribe: | More

This week we’re looking at the confusing and mysterious Canvey Island Monster! Is it really a monster? Is it just a fish, and if so what kind? And who’s telling the truth about what washed up when and where?

The initial article in a Canvey Island newspaper, from CanveyIsland.org.

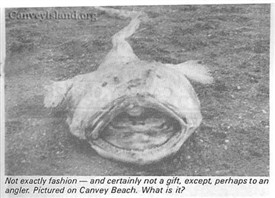

The photo shown on many sites, with the implication or statement that it accompanied the article above:

The photo found by Garth Haslam of Anomoly (highly recommended reading at that link!). Note the enormous difference in font between this newspaper text and the clipping above:

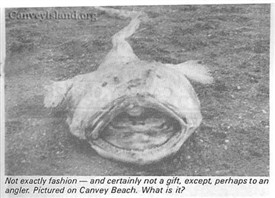

A monkfish:

See also the Frontiers of Zoology page (and scroll way down for the full text of the “mermaid” description).

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

We’re getting closer and closer to Halloween. Things are getting weird. This week we’re going to learn about something called the Canvey Island Monster.

Canvey is a seven square mile, or 18 ½ square km, island off the southern coast of England not far from London. It’s barely above sea level and on Jan 31, 1953, a tidal surge overtopped the sea wall in the night and drowned 58 people. Its marshes are home to lots of plants and animals, including some insects that at one point were thought extinct. It was also a fashionable vacation area in Victorian times and can claim lots of ghost, such as one story told by night fishermen who sometimes see a Viking standing on the mudflats staring out to sea. He supposedly drowned while waiting for his ship to return. But Canvey Island’s big claim to fame these days is something that happened late in the same year of the big flood, 1953.

This is the story as reported pretty much everywhere. Some time in November of 1953, a body washed ashore. We don’t know exactly what day it was or who found it. It was lying in shallow water, and its finders pulled it farther ashore and covered it with seaweed, presumably so nothing would bother it and it wouldn’t wash back out with the tide. They went for the police, but the police had no idea what they were looking at. They called “the government” who sent two zoologists to identify the body. But the zoologists didn’t know what it was either. They had the body incinerated and left without making an official report.

So what did the body look like? It measured about two and a half feet long, or about 76 centimeters. It’s described as a marine animal with thick brownish-red skin, protruding eyes in a pulpy head, sharp teeth, and gills, but it also had hind legs with no forelegs. Remarkably, its feet each had five toes that together were shaped roughly like a horseshoe. The zoologists reportedly said it looked as though it would be able to walk upright on its legs.

Then, in summer of 1954, another one washed ashore. This one was bigger, almost 4 feet long or 120 cm. It weighed about 25 pounds, or 11.3 kilograms. A short article appeared on August 13, 1954 in either the Canvey Chronicle or the Canvey News. There is a clipping on CanveyIsland.org and if you look at the show notes you can see it there too, along with a photograph of the creature.

The headline reads “Fish with feet found on beach.” I’ll read the entire article since it’s very short:

“A fish with feet was found on the beach at Canvey on Tuesday by the Rev. Joseph D. Overs. He described the fish as being over four feet long with staring eyes and a large mouth. Underneath, on its stomach, it had two feet, each with five toes. It was dead and had apparently been damaged by being washed against the rocks. A peculiar fish was found in almost the same place last year and identified as a pocket or ‘fiddler fish.’”

Under that is a subheading titled SEAL TOO and the sentence “For the first time within living memory a seal was seen in Benfleet Creek, near the bridge, on Tuesday.”

All this seems pretty straightforward, but it’s not. There’s a lot to unpack and a lot more information that sheds light on the events. But first let’s take a quick detour to find out what that November 1953 body might have been. What’s a fiddler fish?

There’s a fiddler ray, sometimes called a banjo ray, which I’m delighted to learn is a type of guitarfish. Guitarfish are only slightly guitar shaped. They mostly look like little sharks if you smooshed the shark’s head flat. The fiddler ray has a rounder flattened head than a guitarfish. It lives around Australia and likes shallow, sandy bays, where it eats mostly shellfish and crabs. It’s harmless and edible. But it’s not reddish-brown, it doesn’t have sharp teeth, and it certainly doesn’t have anything that could be called legs by any stretch of the imagination.

I couldn’t find any other marine animals called fiddler fish. As for pocket fish, Google helpfully offered me an urban dictionary entry, gadgets used when fishing, stock photos of plastic fish in shirt pockets, a cookbook, and some miscellaneous entries about video games and songs I’ve never heard of. I couldn’t find an actual fish called a pocket fish.

So we’ll go with the fiddler ray as mentioned in the article. But I just can’t connect a fiddler ray with the thing that supposedly washed up onshore in 1953.

It also seems odd that the newspaper article doesn’t mention the two zoologists supposedly sent by “the government” who couldn’t identify the 1953 monster. For that matter, it doesn’t say that the 1954 fish was the same type of thing found in 1953. It just says “a peculiar fish was found in almost the same place last year”. Not the same kind of fish. The same place. I’ll come back to that in a few minutes.

As it happens, I didn’t have to look too hard to find out how this got so scrambled. I discovered an excellent website called Anomalies that really digs into the topic. A link is in the show notes if you want to read more.

In 1959–only about five years after the weird thing washed ashore on Canvey Island–writer and radio personality Frank Edwards published a book called Stranger Than Science. It’s since been reprinted many times and I have clear memories of reading it as a kid, although I don’t remember anything about the Canvey Island monster. It was a popular book and full of…less than stellar research.

Edwards’ book is the main source used for subsequent accounts of the Canvey Island monster, including the Wikipedia page. It’s Edwards who claims there were two such monsters, Edwards who describes the feet as having toes arranged in a U shape, Edwards who introduces us to the mysterious government-sent zoologists who tell everyone the monster is a bipedal marine animal but it’s okay, it’s harmless, hey, let’s just burn this body and tell no one.

It appears that Edwards made a lot of this up. For instance, there were no baffled zoologists. Why would you even send a pair of zoologists to look at a fish? You’d send an ichthyologist or marine biologist of some kind. Just because someone is trained in the study of animals doesn’t mean they’re good at identifying fish.

The 1954 newspaper story was picked up by the Associated Press, but the full text of the AP article is even shorter than the original, although slightly more sensational, as follows: “A grotesque sea creature four feet long and with two five-toed feet was found on the beach here Tuesday by Reverend Joseph D. Overs. He described the thing, which was dead, as ‘a sort of fish with staring eyes and a large mouth underneath. It has two perfect feet, each with five pink toes.’”

The original 1954 article says that Reverend Joseph D. Overs found the body. According to the CanveyIsland.org page, while Overs was a reverend, he wasn’t the local vicar or anything like that. Apparently he was a reverend of the Old Roman Catholic Church of Great Britain, with a handful of parishioners who met for services at his lodging house. But he was better known as the island’s photographer, and was popular and well-liked. He took the photo of the fish himself, although he may not actually have been the one to find it. The webpage suggests that the reporter included Overs’ title of reverend to give the article more zing and that Overs didn’t usually use his title.

The CanveyIsland.org site is for residents, with a chatty tone, and many of the comments are from people who knew Overs. One 2011 comment about the mystery fish monster, left by a Colin Day, reads: “I was THERE. I was a young lad of nine at the time. I noticed a group of peers in a crowd on the beach. Kids were prodding it with their spades. I ACTUALLY TOUCHED IT! I thought it was a person at first as I could only see part of it through the crowd. Its flesh was NOT fish-like scales. It was a pinkish color and looked like wobbly human flesh with cellulite, orange peel texture. I remember shouting to the other kids ‘It’s a mermaid’ over and over.”

While the fish itself is long gone–no one’s sure what happened to it, but a deep hole in the sand was probably involved, because I bet it stank–we do have that single black and white photograph. What does it show?

It’s a wide-bodied fish with a huge gaping mouth, fins or projections of some kind to either side, and a long, tapering tail. Since it’s a face-on photo, it’s hard to get a good idea of where the fins are situated. They seem to be near the massive head but might be farther back. The fish appears pale, at least in comparison to the dark ground, and we have the eyewitness description of at least one little boy that it was pink, although Edwards claims it was reddish-brown.

Locals are convinced it was an angler fish, and ichthyologists have suggested an anglerfish species known as a monkfish or a related species called a frogfish. Let’s take a look at both.

The monkfish is broad and flattish, with a tapering tail, a big wide mouth with sharp teeth, and two roughly triangular fins jutting out from its sides. It lives in the ocean around England, as well as in the Mediterranean and Black Seas. It hunts among seaweed near the ocean floor, sometimes using its muscular fins to walk itself along instead of swimming. Its skin does not have scales but it is bumpy. Like other angler fish, it has a lure on its head, modified from a dorsal fin spine, that it can move around to attract small fish and other prey. When something touches the lure, YOMP, the monkfish gulps it down. Like the sabertooth fish we talked about in episode 34, the monkfish has an expandable stomach and can swallow prey as big as it is. And it can get big–almost seven feet long for a big female, or over 2 meters.

The frogfish prefers tropical and subtropical oceans, although it does live in the Mediterranean. It’s smaller than the monkfish, barely more than a foot long or around 35 centimeters, and it’s rounded rather than flattened. Some species of frogfish have elaborate filaments called spinules all over their bodies that help them blend in with seaweed and other plants. The frogfish frankly doesn’t look much like the fish in the picture, and is too small to fit the description, but it does have one thing in the plus column that the monkfish doesn’t. Many species are orange, yellow, or pink in color. The monkfish is dark.

But there are more than 200 species of anglerfish known. Many are seldom seen because they live so far down on the bottom of the ocean. In fact, the deep sea anglerfish is the one you’ve probably heard of, the one where the male bites the much bigger female and actually fuses to her body. He remains with her the rest of her life, basically just acting as a built-in egg fertilizer.

In July 1833, six men on a deep-sea fishing vessel caught a three-foot long or just under one meter long fish they claimed was a mermaid. In their sworn statement later they described it carefully, and it’s clear from the description that they had actually caught some species of anglerfish. I won’t quote the entire description here because it’s long, but I’ll link to the Frontiers of Zoology website where I found it. Its back was light gray and its front, as they said–actually the underparts of the fish–were white. They even described its lure, which they thought was some sort of hearing apparatus. So nine-year-old Colin Day was right, in a way. He’d seen a mermaid. And I’m happy to report that the fishermen who’d caught the mermaid in 1833 carefully released it back into the ocean. Because it’s bad luck to harm a mermaid.

So it’s entirely possible that the Canvey Island monster is a species of anglerfish that’s closely related to the monkfish but is pink like a frogfish. Or maybe it was just a variant color or albino. It’s too bad no one kept the fish, but at least we have a photo.

Or do we? We don’t actually know that that photo accompanied the 1954 article. The Anomalist researcher, Garth Haslam, has tried repeatedly to contact a librarian, reporter, or the author of the CanveyIsland.org site to verify the photo’s presence with the original newspaper article, but no one has replied. The Canvey Island library does have archives of one of the two newspapers from that era…but the 1954 papers are missing. Haslam is understandably frustrated and points out that the original description of the fish doesn’t mention its tail, which is quite long and would have been notable. He suggests the picture may actually accompany a different article entirely. He has managed to track down a bigger clip of the fish photo which includes part of a different article’s text next to it…and you know what? The font type is completely different from the font used in the 1954 article. I think Haslam’s right. I don’t think that photo is of the Canvey Island Monster at all.

This was where I was going to laugh like a vampire and wish you a happy Halloween. But then I went and found an article from the Londonderry Sentinel from August 12, 1954. I used up one of my free introductory British Newspaper Archive page accesses to read it, so you’re going to hear the entire thing even though most of it is identical to the Canvey Island newspaper article. But there is one very important addition at the end.

The headline reads ‘Clergyman Finds Fish with Feet’ and the article reads:

“A large fish with feet was found washed up on the beach at Canvey Island, Essex, on Tuesday, by Reverend Joseph D. Overs, a local clergyman. ‘It was over four feet long with staring eyes and a large mouth. Underneath it had two perfect feet, each with five toes. It was dead and had been damaged by being washed against rocks,’ said Mr. Overs. A similar fish was found almost in the same spot at Canvey last November. Mr. Overs said later that the fish had been identified as a pocket fish.

“The fish, which is also known as angler, sea devil, frog or toad fish, and fishing frog, is a British fish, and the name Angler is said to have been derived from its preying on small fish, which it attacts by moving worm-like filaments attached to the head and mouth.”

Now we know that Frank Edwards didn’t completely invent that November 1953 fish. But even if the newspaper picture didn’t come from the 1954 article—and I’m pretty sure it didn’t—it seems clear from this article that we’re talking about anglerfish anyway. Even the 1953 fish’s identification as a fiddler fish isn’t too surprising, since the fiddler ray does superficially resemble an anglerfish in that it has a large head but a much slenderer body that tapers in a long tail. The angler fish’s fins are strong and thick, and if the body was damaged as Overs reported, the ends of the fins may have been frayed to resemble toes.

But I do have one last thing to add. Remember how in Stranger Than Science, Frank Edwards describes the fish as having five toes arranged in a U shape? Where on earth did that come from? Well, for some reason Edwards was convinced that the Canvey Island Monster was the same thing that left hoofmarks in the snow all over Devonshire in February of 1855. No one else has made that connection and I have no idea why Edwards decided to link them. Devon and Canvey are over 200 miles apart, or about 360 kilometers. But if Edwards wanted to use the Canvey Island Monster to solve the mystery of the devil’s footprints, he had to make people believe not only that the fish was bipedal but that it had feet whose prints would resemble hooves.

I don’t think the Canvey Island monster was out cavorting in the snow in 1855, leaving hundreds of miles of hoofmarks on roofs and in walled gardens. But something left those hoofmarks. But to learn more about the devil’s footprints, you’re going to have to wait for next week.

[thunder crash muahaha!]

You can find Strange Animals Podcast online at strangeanimalspodcast.com. We’re on Twitter at strangebeasties and have a facebook page at facebook.com/strangeanimalspodcast. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. If you like the podcast and want to help us out, leave us a rating and review on iTunes or whatever platform you listen on. We also have a Patreon if you’d like to support us that way. Rewards include stickers and twice-monthly bonus episodes.

Thanks for listening!