Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 12:18 — 12.3MB)

In this week’s episode, we look at a couple of so-called living fossils: the tuatara and the lamprey. One of them hasn’t changed appreciably in almost 400 million years. Tune in to find out which one and learn about how gross it is and how cute the other one is! (I may be biased.) (re-recorded audio)

The adorable tuatara! It eats anything, including baby tuataras. Not cool, lizardy guy:

A face not even a mother could love. The sea lamprey:

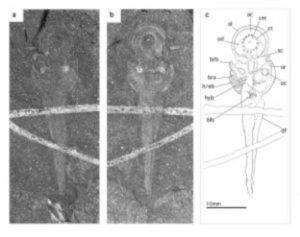

A recently discovered fossil lamprey, complete with impression of its body:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

This week’s episode is about my favorite reptile and a revolting sea creature, and just to be clear, those are two different animals.

If you look at a tuatara, it appears pretty ordinary. It’s a brownish-grayish-green lizard with lighter-colored spines along its back, and it can grow to about two feet long, or 61 cm. It’s a hefty lizard, sure, but you’d probably think it was nothing special. But dang, is it special.

First of all, it’s not strictly a lizard. It’s the only surviving member of its own order, Rhynchocephalia. It also has many physical traits not shared by lizards—or any other living reptile. Or mammal. Or bird. Or anything else.

Its teeth, for instance. The tuatara has two rows of teeth in the upper jaw, one in the lower, with the lower jaw’s teeth fitting neatly between the two upper rows. Some snakes have two upper rows of teeth and one lower row, but not arranged like the tuatara’s. Not to mention that the tuatara’s teeth aren’t even teeth at all. They’re just pointy projections of the jaw bone.

The tuatara also chews in a literally unique way. When the lower teeth mesh between the upper rows of teeth, the animal moves its jaw forward and back. This slices its food against the sharp tooth edges.

The tuatara also has a third eye. I’m not making this up. It legit has a photoreceptor on top of its head called the parietal (pahRAYetal) eye with a lens, cornea, retina, and so forth. Hatchling tuataras have a translucent patch of skin above the eye, but as the hatchling grows and molts its skin, the patch darkens until the third eye is no longer visible. Researchers think it may help with thermoregulation and hormone production. The tuatara isn’t the only creature with a third eye, but it has the most well developed one.

Like the turtle, the tuatara has a primitive auditory system. It has no external ears and no eardrum, although it can hear. Its skeleton has some features apparently retained from its fish ancestry, such as its spine and some aspects of its ribs. Males don’t have a penis—but a lot of birds don’t either and we still have lots of birds, so obviously they make it work.

Because it has such a slow metabolism—the lowest body temperature of any other reptile—the tuatara grows slowly. It won’t reach breeding age until it’s ten to twenty years old, and females only lay eggs about once every four years. The average lifespan of a tuatara is 60 years. Researchers believe it could live to 200 years in captivity.

Baby tuataras are active in the daytime, probably so their parents won’t eat them. Tuataras eat pretty much anything they can catch. Adult tuataras are active at night, and sleep during the day in dens. Sometimes a tuatara digs its own den, sometimes it shares a den with burrowing seabirds. The birds leave in the morning and the tuatara comes home to sleep until night, when the birds return.

The Tuatara is native to New Zealand, and in an all-too-common situation, when people showed up, the tuatara promptly went extinct on the mainland. It was restricted to 35 islands where it was mostly safe from introduced rats, until its reintroduction in the fenced Karori Sanctuary in 2005. Tuataras have begun to breed in the sanctuary.

One thing I didn’t know about New Zealand—one of many many things, since pretty much all of my New Zealand knowledge comes from watching the Lord of the Rings movies, is that it was underwater for millions of years. Some 82 million years ago, New Zealand separated from Gondwana, the chunk of land that eventually separated into the southern continents we know today. The entire continent containing New Zealand was partially drowned some 25 million years ago, and for a long time scientists thought New Zealand was completely underwater. In the late 2000s, though, a fossil tuatara was found in New Zealand that was dated to about 18 million years ago. If New Zealand was underwater for a few million years, how did the tuatara recolonize it after the sea receded? Tuataras are not good swimmers, and it’s a long distance to float on driftwood without water.

Researchers now think that the highest elevations of New Zealand remained above sea level, allowing tuataras and some other species of plants and animals to survive the inundation.

You’ll see the tuatara referred to as a living fossil in a lot of articles. The media loves to call things living fossils. The tuatara has been around for 225 million years, but so have crocodiles and alligators. In fact, crocs and gators are found in the fossil record even earlier, 250 million years ago. The tuatara in particular has a lot of modern adaptations, including a number of cold-weather adaptations. A 2008 study discovered that the tuatara has the highest molecular evolution rate of any animal ever measured.

Basically, you can’t keep the tuatara down. Drown its entire continent? No problem. Run a couple of ice ages through there? It’ll adapt. And now we realize that this isn’t even its final form.

I take you now from a chunky little lizardy thing eating crickets in New Zealand to a two-foot-long monstrosity that drills into living creatures to drink the blood and bodily fluids it rasps from their tissues, the sea lamprey.

What does the tuatara have to do with the sea lamprey? I mean beyond the fact that the tuatara would happily slurp up any lampreys it could get into its mouth? Well, if the tuatara is the most rapidly evolving creature ever studied, the lamprey has remained basically unchanged for at least 360 million years.

Lampreys are eel-like parasites that lack jaws. Instead, they have a circular mouth rimmed with rows and rows of rasping teeth, for lack of a better word. I saw this described in one paper as a feeding apparatus, and it’s as good a description as any although it doesn’t convey the utter, utter horror that is the lamprey’s mouth. I may be showing my prejudices here.

Those aren’t teeth, by the way, they’re made of cartilage. The lamprey doesn’t have any bones at all, but it does have a cartilage tooth-studded tongue used to drill into its prey once it’s clamped on with its sucker-like mouth. Dear God.

Not all lampreys are parasitic. Some are filter feeders as larva and don’t eat at all once they grow up, just live on their bodily reserves until they breed and die, but I’m just talking about parasitic lampreys today because they’re gross. The most common parasitic lamprey is the sea lamprey, which lives in the Atlantic Ocean, parts of the Mediterranean and Black Seas, and in the Great Lakes as an introduced pest. The sea lamprey can grow up to four feet long, or 120 cm.

Because of their lack of bone, lampreys don’t fossilize well, but one fossil found in South Africa has revealed a lot about the lamprey. In a 2006 paper in Nature, researchers describe a beautifully preserved lamprey dated to 360 million years ago. Not only are the gills and mouth perfectly visible, so is an impression of its body. It was the oldest lamprey fossil found at the time, and it shows that the lamprey basically hasn’t changed ever since. If anything deserves to be called a living fossil, it’s the lamprey.

Back when the lamprey first evolved, it wasn’t preying on true fish. There weren’t any yet. The lamprey has held fast through at least four major extinction events. It’s a vertebrate, but has never evolved those things other vertebrates—except the hagfish, which is just weird—have developed: jaws, scales, paired fins. On the other hand, some lampreys do have a third eye.

Because lampreys are so primitive from an evolutionary standpoint, scientists can study them to learn how other vertebrates evolved. For instance, the lamprey has seven pairs of gill arches. In other vertebrates, the interior pair of gill arches evolved into upper and lower jaws and middle ear bones. That includes us.

Lampreys today prefer fresh water that’s not too warm, although the sea lamprey spends most of its adult life in the ocean, although it will also be fine in fresh water. The sea lamprey migrates upriver to spawn. After the female lays her eggs, she and the male both die. When the eggs hatch, the larvae migrate downstream to quiet water where they feed on plankton until they metamorphose into adult lampreys. Then they continue their migration downstream to the ocean or lake. They live about a year before returning upstream to spawn and die.

Lamprey larvae live as filter feeders, and until about 2014 scientists didn’t know if this was a recent development or not. Then some fossilized lamprey larvae were discovered in inner Mongolia rocks dating back 125 million years, and they look identical to modern larvae.

Old and “primitive” as it is, the lamprey is able to tolerate all sorts of environments. Most water animals can either live in saltwater or freshwater, not both, but the sea lamprey does just fine in either. In the Great Lakes, sea lampreys are so damaging to the native fish that researchers have been trying for decades to get rid of them. The sea lamprey can also feed on fish that are toxic to pretty much any other predator.

In many cultures, lamprey is considered a delicacy, and it’s supposed to taste quite good, but make sure you clean those things well. Their mucus is a toxin. You will not catch me eating lamprey if I can possibly avoid it.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast online at strangeanimalspodcast.com. We’re on Twitter at strangebeasties and have a facebook page at facebook.com/strangeanimalspodcast. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. We also have a Patreon if you’d like to support us that way.

Thanks for listening!