Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 22:24 — 23.0MB)

This week we’ll learn about five mystery fish that William Beebe spotted from his bathysphere in the early 1930s…and which have never been seen again. Thanks to Page for suggesting deep-sea fish!

Further reading:

How some superblack fish disappear into the darkness of the deep sea

Further listening:

The Gulper Eel unlocked patreon episode

These two guys crammed themselves into that little bathysphere together. Sometimes they got seasick and puked in there. Also, they didn’t like each other very much:

The Pacific blackdragon is hard to photograph because it’s SUPERBLACK:

A larval blackdragon. Those eyestalks!

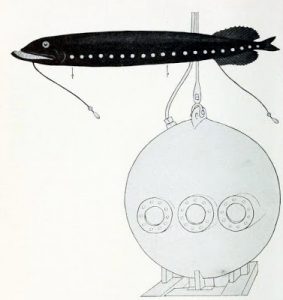

A painting (by Else Bostelmann) of Bathysphaera intacta (left) and an illustration from Beebe’s book Half Mile Down:

The pallid sailfish, also painted by Bostelmann:

A (dead) stoplight loosejaw. Tear your surprised eyeballs away from its weird jaws and compare its tail to the pallid sailfish’s:

A model of a loosejaw (taken from this site) to give you a better idea of what it looks like when alive. Close-up of the extraordinary jaws (seen from underneath) is on the right:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

This week we’re going to descend metaphorically into the depths of the ocean and learn about some mystery fish spotted once from a bathysphere by famous naturalist William Beebe and never seen again. Deep-sea fish is a suggestion by Page, so thank you, Page, for a fascinating and creepy addition to monster month.

William Beebe was an American naturalist born in 1877 who lived until 1962, which is amazing considering he made repeated dives into the deep sea in the very first bathysphere in the early 1930s. We talked about bathyspheres way back in episode 27–you know, the one where I scream about them imploding and kind of freak out a little. Even today descending into the deep sea is dangerous, and a hundred years ago it was way way way more dangerous.

Beebe was an early conservationist who urged other scientists to stop shooting so many animals. Back then if you wanted to study an animal, you just went out and killed as many of them as you could find. Beebe pointed out the obvious, that this was wasteful and didn’t provide nearly as much information as careful observation of living animals in the wild. He also pioneered the study of ecosystems, how animals fit into their environment and interact with it and each other.

While Beebe mostly studied birds, he was also interested in underwater animals. Really, he seems to have been interested in everything. He studied birds all over the world, was a good taxidermist, and especially liked to study ocean life by dredging small animals up from the bottom and examining them. He survived a plane crash, was nearly killed by an erupting volcano he was observing, and fought in WWI. Once when he broke his leg during an expedition and had to remain immobilized, he had his bed carried outside every day so he could make observations of the local animals as they grew used to his presence.

In the 1920s, during an expedition to the Galapagos Islands, he started studying marine animals more closely. First he just dangled from a rope over the surface of the ocean, which was attached to a ship’s boom, but eventually he tried using a diving helmet. This was so successful that he started thinking about building a vessel that could withstand the pressures of the deep sea.

With the help of engineer Otis Barton, the world’s first bathysphere was invented and Barton and Beebe conducted dozens of descents in Bermuda, especially off the coast of Nonsuch Island. The bathysphere had two little windows and a single light that shone through one of the windows, illuminating the outside just enough to see fish and other animals. The bathysphere couldn’t descend all that deeply, although it set records repeatedly. The deepest they descended was 3,028 feet, or 923 meters, but Beebe made careful notes of all the animals he observed and published many articles and books about them. Many of these articles and books were illustrated by an artist named Else Bostelmann, who worked closely with Beebe and his team of scientists. Bostelmann even painted underwater while wearing a diving helmet, because she needed to know how colors were affected by underwater light. She used oil paints, since oil and water don’t mix so the paints wouldn’t wash away, and she tied strings to her paintbrushes so they wouldn’t float off.

Incidentally, if you’re interested in reading a really interesting article about Bostelmann or learning more about the bathysphere and William Beebe, check the show notes. I’ve included links to the article and to a 99% Invisible episode about the bathysphere.

Many of the animals Beebe saw from the bathysphere have since been identified and described by later scientists. But there are five fish that Beebe observed that have never been seen since.

Before we talk about them, let’s learn about Page’s suggestion, the Pacific blackdragon, for reasons that will shortly become clear. The Pacific blackdragon is a type of fish that lives in the Pacific, which you probably figured out without me telling you. It prefers tropical and temperate water, although since it’s a deep-sea fish the water where it lives is mostly very cold.

If you remember episode 155 about extreme sexual dimorphism, where the males and females of a species look radically different, this fish is a good example. The male never eats. He can’t eat. He doesn’t have a functioning digestive system. He survives on the yolk from the egg he develops from and never grows any larger than his larval form, about three inches long, or 8 cm. He lives long enough to mate and then he dies.

The female, however, grows up to about two feet long, or 61 cm. Her body is long and thin, and her mouth is full of sharp teeth that she uses to grab anything she can catch. She especially likes to eat fish and small crustaceans, but she’s not picky.

Her body is black, and not just regular black. It’s called superblack or ultrablack. In episode 186 we talked about the eyed click beetle and velvet asity who both have superblack markings that absorb most of the light that hits them. Well, the Pacific blackdragon is superblack almost all over to help hide in the darkness of the water, since it’s an ambush predator. Just under the fish’s skin, there’s a layer of closely packed pigment-containing structures called melanosomes, which can absorb up to 99.95% of light. As if that wasn’t enough, because a lot of the animals the blackdragon eats emit bioluminescent light, her stomach is also black to block any light from the prey she’s swallowed. But although she’s basically invisible to other animals, she does have several rows of light-emitting cells called photophores along her sides. Scientists think she uses the lights to attract a mate, but she only flashes the photophores occasionally and only for brief moments. She also has a barbel that hangs from her chin with a luminescent lure at the end, which she uses to attract prey.

While the Pacific blackdragon is a deep-sea fish, at night she migrates upward nearer the surface to catch more prey, although she still stays below about 1,300 feet deep, or 400 m. She has large eyes as a result to take advantage of any moonlight and starlight that shines down that far. During the day she stays deeper, up to 3,200 feet deep, or 1,000 m.

Speaking of the Pacific blackdragon’s eyes, larval blackdragons have eyes on long stalks—really long stalks, nearly half their body length. As the larva matures, it absorbs the stalks until the adult fish has ordinary fish eyes. The larvae are also mostly transparent.

There are two other blackdragon species known, both of them a little smaller than the Pacific blackdragon. But in 1932 William Beebe spotted a fish that he thought might be related to the blackdragons, except that he estimated it was six feet long, or 1.8 m.

Beebe named the fish Bathysphaera intacta, but there’s no type specimen so no one can study it and verify whether it’s a species of blackdragon or something else. Beebe said the fish he saw had large eyes, lots of teeth, and photophores along its sides that glowed blue, and had a barbel with a light under its chin just like the Pacific blackdragon and its cousins. But it also had another, smaller barbel with a light near the tail. Beebe saw two of the fish together. They circled the bathysphere a few times, probably attracted to its light.

Another of Beebe’s mystery fish is one he named the pallid sailfin, Bathyembryx istiophasma. He saw it twice on the same descent in 1934, and described it as about two feet long, or 61 cm, shaped like a cigar with triangular fins and a tiny tail. In fact, in his book Half Mile Down Beebe described the fish this way:

“The strange fish was at least two feet in length, wholly without lights or luminosity, with a small eye and good-sized mouth. Later, when it shifted a little backwards I saw a long, rather wide, but evidently filamentous pectoral fin. The two most unusual things were first, the color, which, in the light, was an unpleasant pale olivedrab, the hue of water-soaked flesh, an unhealthy buff. It was a color worthy of these black depths, like the sickly sprouts of plants in a cellar. Another strange thing was its almost tailless condition, the caudal fin being reduced to a tiny knob or button, while the vertical fins, taking its place, rose high above and stretched far beneath the body, these fins also being colorless.”

Beebe assigned the pallid sailfish into the family Stomiidae, the same family that Bathysphaera intacta is assigned to as well as the other blackdragons. As a group, the fish in this family are called barbeled dragonfish. Some species in this family do show a similar tail arrangement that Beebe noted, with a very small tail fin but enlarged anal and dorsal fins that are set well back on the body. This includes a weird fish with various names, including black hinge-head, black loosejaw, or lightless loosejaw, which maybe gives you an idea of what it looks like. It’s a deep-sea fish like all the barbeled dragonfish, and it’s black in color. It grows about 10 inches long, or almost 26 cm. It’s also sometimes called the stoplight loosejaw because it has two photophores on its head, one of which shines green, the other which shines red. Unlike most deep-sea fish, it can see in the red spectrum, so the green photophore may attract prey and the red photophore allows the loosejaw to see its prey even though the prey can’t see the loosejaw. But mainly, it has remarkable jaws.

The loosejaw’s jaws are hinged and extremely large compared to the body, which is fairly thin. The jaws are so large that they’re not even attached to its body, just to its head. They aren’t even connected to the body with skin. It’s hard to describe, but I have some good pictures of a model of the fish in the show notes. Basically, the jaws are just bones covered with a thin layer of skin, but no skin or muscle in between the bones. If you put your thumb under your chin, you can feel your chin bone, then move your thumb backwards and instead of bone, you feel skin over layers of fat and muscle and other tissues that make up the soft part of your jaw. Well, the loosejaw doesn’t have those soft parts. It just has the chin bone and there’s literally nothing between the jaws. It doesn’t have a throat or cheeks or anything like that. Its jaws aren’t big because it needs to swallow big things, its jaws are big so it has a longer reach to snag the small fish and crustaceans it eats. It has a lot of needlelike teeth that it uses to keep its prey from wriggling away while it maneuvers it into its gullet. It mostly eats very small animals, but it’s not going to let anything get away once it gets within jaw range.

While I was researching this episode, I spent a ridiculous amount of time trying to find the episode where I talked about the umbrellafish, thinking it might be related to the loosejaw. It’s not, and I finally realized the umbrellafish episode was for patrons. I’ve unlocked that Patreon episode and linked to it in the show notes if you want to go listen to it. The umbrellafish, also called the gulper eel, looks superficially like the loosejaw, but it has skin over its huge hinged jaws.

After my inability to properly describe the loosejaw’s amazing jaws, let’s move on to Beebe’s other mystery fish. One he named the three-starred anglerfish, Bathyceratias trilychnus, which he estimated was about six inches long, or 15 cm. It had three bioluminescent illicia on its head that it probably used as lures, since that’s something that other deep-sea anglerfish do and Beebe was pretty sure it was actually a species of anglerfish. Since there are over 200 known species of anglerfish, it’s not surprising that there are more that aren’t known.

Another was the five-lined constellation fish, Bathysidus pentagrammus, named for the five rows of photophores on its sides. Beebe thought it looked kind of like a surgeonfish, which is a flat, round fish shaped sort of like a pancake with fins and a tail. But surgeonfish are mostly found in shallow, tropical waters around coral reefs. They’re often brightly colored. Beebe didn’t assign his constellation fish to the surgeonfish’s family, and in fact didn’t assign it to any family since he didn’t know where it belonged.

The last of Beebe’s mystery fish was the rainbow gar, which he didn’t give a scientific name to since he had no idea what kind of fish it might be. He thought it was shaped like a gar, but it was so extraordinary he didn’t know what to think. He actually saw four of them swimming almost vertically, heads up and tails down, at about 2,500 feet deep, or 760 m. He named them rainbow gar because of their coloring: bright red head and jaws, a light blue body, and a yellow tail. They were about four inches long, or a little over 10 cm, with long, pointed jaws. They moved by fanning the dorsal fin, sort of like a seahorse.

Beebe wrote scientific articles about some of these fish and included them all in his book Half Mile Down. But it wasn’t long before other scientists started doubting the sightings. Some people thought he’d made up the fish to make his expeditions more exciting, some thought he was just mistaken. One irate ichthyologist wrote in 1933 that the constellation fish was probably just light reflecting off Beebe’s own breath fogging the window, because no fish had photophores like the ones he described. Because I guess in 1933 everything was known about fish that would ever be known, right?

Beebe seems to have been an honest scientist, though, and he didn’t really need to make anything up. He discovered dozens, if not hundreds, of fish new to science, many of which have either been found and properly described later, or which Beebe himself managed to later catch. Whenever he and Barton came up from a descent in the bathysphere, Beebe had his team on the boat send down nets, and sometimes they caught some of the animals he had seen. This allowed Bostelmann to add details to her paintings that Beebe wouldn’t have known about from just a look through the bathysphere’s windows.

Not only that, if Beebe wanted to make up a fish that would excite the general public and make them want to buy his books, he would have made up something huge and frightening. His mystery fish are mostly quite small. Only Bathysphaera intacta was large, and he only said they were about six feet long. That’s big for a deep-sea fish, but remember that the bathysphere never made it to the really crushing depths of the abyss. It descended into the mesopelagic zone, which is extremely dark but not completely lightless. There’s also a lot of life in this zone, and many fish that spend the day here migrate nearer the surface at night where they can find more food while still remaining hidden. The long-snouted lancetfish lives in this zone and it can grow seven feet long, or 2.15 m.

Plus, Beebe didn’t need to convince anyone to buy his books. They were already runaway bestsellers and he was quite famous, although it seems not to have gone to his head. He just wanted to have fun and do science. He actually seems to have been a good person by modern standards too, which is always refreshing. He disagreed with people who claimed to have scientific proof that women were inferior to men or that some races were inferior to others. He insisted that his team members work hard, but he worked hard too, and if he thought everyone was feeling too stressed, he’d announce that his birthday was coming up and they should take a few days off to celebrate. Some years he had several birthdays.

Beebe did spot one other mystery animal, but he didn’t get a good enough view to make a guess as to what it might be. This is what he wrote about it:

“…I saw its complete, shadow-like contour as it passed through the farthest end of the beam [of light]. Twenty feet is the least possible estimate I can give to its full length, and it was deep in proportion. The whole fish was monochrome, and I could not see even an eye or a fin. For the majority of the ‘size-conscious’ human race this marine monster would, I suppose, be the supreme sight of the expedition. In shape it was a deep oval, it swam without evident effort, and it did not return. That is all I can contribute, and while its unusual size so excited me that for several hundred feet I kept keenly on the lookout for hints of the same or other large fish, I soon forgot it in the (very literal) light of smaller, but more distinct and interesting organisms.

“What this great creature was I cannot say. A first, and most reasonable guess would be a small whale or blackfish. …[O]r, less likely, it may have been a whale shark, which is known to reach a length of forty feet. Whatever it was, it appeared and vanished so unexpectedly and showed so dimly that it was quite unidentifiable except as a large, living creature.”

Twenty feet is six meters, by the way. It might easily have been a whale, since many species of whale routinely dive much farther than the bathysphere descended at its deepest. Whatever it was, and whatever Beebe’s other five mystery fish were, hopefully one day a modern deep-sea vehicle will find them again.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast online at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. If you like the podcast and want to help us out, leave us a rating and review on Apple Podcasts or just tell a friend. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us that way. Don’t forget to enter our book giveaway if you haven’t already, too! Details are on the website.

Thanks for listening!