Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 22:46 — 16.8MB)

This week we’re learning about some out-of-place marsupials, from phantom kangaroos to colonies of wallabies living in places like England and Hawaii. Thanks to Richard E. for the suggestion!

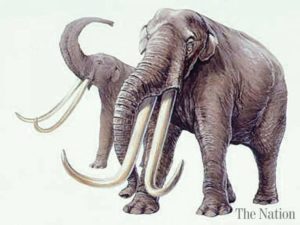

A Bennett’s wallaby and a red kangaroo:

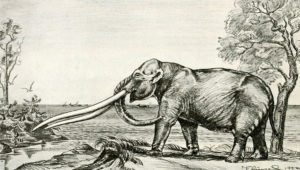

George Stubbs’s kangaroo painting:

The controversial maybe-it’s-a-kangaroo engraving from 1593 (detail to the right). For more information, this is a great article.

You can find the 2013 video of a kangaroo in an Oklahoma cowfield here. It’s definitely a kangaroo, too.

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

We started 2018 with a couple of episodes about out of place animals. I meant to make that a regular feature this year, but I keep getting distracted. Imagine that. This week I was going to revisit out of place animals in general, with lots of excellent suggestions from Richard E. But the second I started researching some populations of wallabies in places far outside of their usual home, I got sucked into the strange world of phantom kangaroos.

Reports of so-called phantom kangaroos are something between an urban legend and a genuine cryptozoological mystery. The problem with the earliest accounts is that they’re impossible to verify as real reports. Newspapers from earlier than about the 1920s would sometimes play fast and loose with reality in order to sell papers or just fill space. I suspect that at the time, most people reading the papers understood that these sorts of accounts were just fun nonsense, but we don’t have the same frame of reference to interpret them properly today. A hundred years from now scholars are going to be reading memes from 2018 and taking them at face value because they don’t understand most of the pop culture references.

But let’s dig into some of these phantom kangaroo reports and see what we can find out.

The first report of a phantom kangaroo is usually listed as one from 1899 in Wisconsin. The story goes that on June 12 of that year, a woman in New Richmond reported seeing a kangaroo run through her neighbor’s yard. Some accounts say it was her yard, and some reports say it happened during a storm. Some reports also mention that a circus was in the area, but that while people assumed the kangaroo had escaped from the circus, it turned out that the circus had never had a kangaroo.

This story doesn’t seem to appear anywhere except books and websites about unexplained phenomena. On the surface it seems to have good details, but when you think about it, it’s mostly vague. We have a specific date and a specific place…but what was the woman’s name? Which circus was in town? How did the woman know she had seen a kangaroo, and what did it look like? It was described as running, not hopping, but does that verb come from the witness or from reporters?

The next phantom kangaroo account is from 1907, and supposedly happened near Pennsburg, PA. I found it in three old newspapers, including the August 3, 1907 Harrisburg (Pennsylvania) Telegraph, and the Harrisburg Daily Independent.

This is the text of the article that appears in both those newspapers, with the headline “Kangaroo” at Large Alarms a Community, with Kangaroo in quotes, a rather sophisticated touch that makes me think the story was real:

“Pennsburg, Pa, Aug. 3 Tales of a kangaroo that is said to be roaming the wooded hills in the vicinity of Pleasant Run, a few miles west of here, have occasioned intense excitement in that region. Several persons, among them Erwin Styer and Martin Stengel, have seen the strange animal within the last week, and while it is so fleet that no one has been able to obtain a good view of it, the descriptions tend to substantiate the theory that it is a kangaroo. Dogs have attacked the animal, but have always been worsted. People living in the neighborhood of Pleasant Run are afraid to venture away from home after nightfall, and there is little disposition to linger long at the village store in the evening.”

unquote

I checked and Pleasant Run, Pennsylvania is indeed four miles away from Pennsburg, so that’s accurate. I also found an article in the Pinedale (Wyoming) Roundup of December 4, 1907, with the headline “Big Kangaroo at Large” and the subheadline “Keeps Lovers from Their Sweet Summer Saunterings,” which makes me want to throw up a little. This version of the story has been expanded, but whether that was done by the original reporter or was added to give the story more flavor, I don’t know. Here it is in full:

Quote

“Tales of a kangaroo that is said to be roaming the wooded hills in the vicinity of Pleasant Run, a few miles west of here, have occasioned intense excitement. Several persons, among them Erwin Styer and Martin Stengel, have seen the strange animal within the past week, and while it is so fleet that no one has been able to obtain a good view of it, the descriptions substantiate the theory that it is a kangaroo. It is described as being of gray color, with a head shaped like that of a sheep and a body of large proportions. Upon the approach of a human being it darts away at tremendous speed.

“Dogs have attacked it, but were always worsted. They were not bitten but apparently the animal flung them off with terrific force in the manner that a kangaroo defends itself with its hind legs and tail.

“People living in the neighborhood are afraid to venture away from home after nightfall and there is little disposition to linger at the village store or tavern in the evening. Young men say that the customary outdoor rural amusements are no longer safe. ‘It ain’t that I’m afraid of any wild beast that ever roamed the jungles of Montgomery county,’ said one young swain, ‘but I certainly do object to the disgrace of being knocked out by the hind legs or the tail of a kangaroo. So I guess we fellows won’t do much stirring up with the girls for some time to come.’”

Unquote

Okay, first of all, barf. Second of all, I don’t know what people sounded like in 1907, but I lived in Pennsylvania for a while and no one talks like that there. Third of all, I’m pretty sure Montgomery County, PA, which is not far from Philadelphia, wasn’t exactly a jungle even in 1907. I guarantee you that the quote at the end of the Wyoming article was made up by some bad writer, either in Wyoming or in some other newspaper, to give it more pizzazz.

It’s possible the whole article was an invention. I suspect the original version reports a real event, but since there are so few details it’s impossible to know if the animal was actually a kangaroo.

The next phantom kangaroo is a lot more interesting. It happened near South Pittsburg, Tennessee, which is near Chattanooga and therefore not far from where I live. Over five days in January 1934, an animal people called a kangaroo was repeatedly seen outside the town. One person said it leaped across a field, others reported it had killed and partially eaten some dogs and ducks, and was even reported carrying away a sheep. Its prints were tracked to a cave, but the animal was never found. Now, I’m going to be honest here and admit that I didn’t hunt too hard for original newspaper articles on this one. I should have, but I literally ran out of time. Basically, whatever this animal was, it probably wasn’t a kangaroo. While kangaroos, like all herbivores, will occasionally eat birds or small animals, or even fish, they don’t eat dogs. They don’t live in caves. They aren’t usually aggressive at all. So basically, while it’s possible this was a mystery animal, it wasn’t a kangaroo.

People tend to see what they expect to see. If someone sees an animal they can’t identify, their subconscious will suggest the most plausible mystery animal. These days that might be Bigfoot or a dogman. In the olden days, it might have been a kangaroo. But why? Why kangaroos?

Kangaroos have been known to science and to general non-Australian people for centuries. The most famous painting of a kangaroo was by artist George Stubbs, who is best known for his gorgeous paintings of horses and dogs. Stubbs painted it in 1772 from a skin brought to England by Captain Cook, not from a live animal. As a result, the kangaroo isn’t as accurate as most of his paintings, but it’s still definitely a kangaroo. It was exhibited in London in 1773 and was a huge attraction. Prints and reproductions of Stubbs’s kangaroo were also popular, and until zoos started to exhibit live kangaroos, that’s what many non-Australians thought kangaroos looked like.

But there were earlier European depictions of kangaroos and other marsupials from Australia, definitely as early as 1711 and possibly as early as 1593. People do tend to see what they expect to see, but presumably no one outside of Australia actually expects to see a kangaroo hopping around on any given day. But something did happen around the time of the earliest phantom kangaroo reports. Kangaroos and their relations started being exhibited in zoos.

This is different from traveling menageries and circuses. The first kangaroos were known to have been in traveling menageries around 1828, when one or two kangaroos were exhibited in England, with a few others in circuses and menageries traveling mostly around Boston and Ontario in North America. But public zoos became more and more common around the late 18th and early 19th centuries, especially in the United States. Kangaroos and their smaller relations, wallabies, started to appear in American zoos in the early 20th century.

So it’s possible that the phantom kangaroo sightings resulted from more people being familiar with what kangaroos were and what they looked like, but not being familiar with what they ate or how they acted outside of captivity. Zoos in those days were grim places, with animals kept in small cages, so many people who saw one on display may not even have been aware they hop instead of run. If your sole experience with hopping animals is rabbits, and someone told you kangaroos hop, you’d probably picture a rabbit-like gait.

But…well…maybe people were actually seeing kangaroos, at least sometimes.

Here’s the thing. Kangaroos and wallabies are sometimes kept as pets. Apparently they can get pretty tame, although I’m just going to point out that you’d be a lot better off with a pet that’s actually domesticated. If you must have a hopping pet, rabbits are pretty awesome. Anyway, guess what. There are actual known populations of wallabies living in various places where they really shouldn’t be. And we don’t actually know how they got there in most cases. All we can do is guess they were escaped pets or escaped from zoos.

Wallabies look like miniature kangaroos, maybe the size of an average dog. They eat all kinds of plants, can bound quickly and jump fences and other obstacles, and are largely nocturnal although they also come out in daylight. Basically they fill a similar ecological niche as deer. They breed well in captivity and are cute, so are often kept in zoos. They’re marsupials native to Australia, New Zealand, and New Guinea…but they are also found in parts of England, Scotland, Ireland, on the Isle of Man, in one tiny area of France, and a few other places.

We do know where some of the wallabies come from. Lady Fiona of Arran was a bit of an eccentric who kept what would have been considered exotic pets back in the 1920s and 30s: llamas, alpacas, pot-bellied pigs, and wallabies. At some point in the 1940s she turned the wallabies loose on an island in Loch Lomond, where they’ve lived ever since. The problem, of course, is that they shouldn’t really be there. They’re cute, sure, and tourists do come to see them, but some people think their presence threatens certain native bird species and they ought to be killed off, or at least captured and taken to zoos. Other people point out that the native birds on the island don’t seem to be bothered by the wallabies, which after all have been there for the better part of a century now. About sixty wallabies live on the island at any given time.

There are also wallabies in the Peak District in Derbyshire, England. This was the population Richard E. told me about, which got me started on this episode that has taken me way too long to research. We know where these wallabies came from too. A man named Henry Courtney Brocklehurst, which honestly does not even sound like a real person’s name, once kept a private zoo on the Roaches, a rocky ridge that’s part of a national park in England. At some point in the 1930s five wallabies in his zoo either escaped or were quietly turned loose, reports vary. They did well in the wild and multiplied, until at their most numerous there were around 50. For a while people thought the wallabies had all died off after some especially cold winters, but in 2009 a hiker got pictures of one.

But wallabies also live in other parts of the British isles, and we don’t know where most of them came from. At least some are probably escaped pets or escaped from zoos—wallabies are apparently pretty good at escaping—while others may be individuals from the peak district population that have gone wandering. All the wallabies in Britain are a subspecies of red-necked wallaby called Bennett’s wallaby, which is from Tasmania. This means it’s better adapted to the British climate than most other wallabies would be. They’re sometimes killed by cars or dogs.

So let’s get back to more modern sightings of phantom kangaroos. There are a lot of reports from the United States, believe me, and a few from Canada. I won’t go into detail for most of them, but they include a 1949 sighting in Ohio, a 1958 sighting in Nebraska, the “Big Bunny” kangaroo sightings in Minnesota that persisted for a decade between 1957 and 1967, and many more.

On October 18, 1974 someone called the Chicago police to report a kangaroo on their porch. Two officers responded…and found a kangaroo in a nearby alleyway. They reported it was five feet tall, or 1.5 meters, which points to its being an actual kangaroo and not a wallaby. Now, Chicago cops probably are not trained to deal with kangaroos, but you’d think they would have the sense to call animal control or a zoo or someone who does know how to deal with kangaroos. Instead, they decided to treat the kangaroo like a human criminal. That’s right, they tried to handcuff a kangaroo.

The kangaroo kicked and punched the officers, who called for backup and probably still haven’t lived that down, but the kangaroo jumped a fence and disappeared into the night.

The next day a paperboy near Oak Park reported hearing a car’s brakes squeal, and when he turned to look, he saw a kangaroo only a few feet away, staring at him. It hopped away. Over the next few weeks sightings poured in from all over Chicago, from other Illinois cities, and even from Indiana. By July 1975, sightings had tapered off and finally stopped.

In April 1978, a schoolbus driver in Waukesha, Wisconsin saw two kangaroos hop across the road. She wasn’t the only one to see them, either. The road was busy and drivers had to slam on their brakes to avoid the kangaroos. One driver actually hit one, but it just jumped back up and hopped away. More people spotted the kangaroos in the weeks that followed. By the end of the month, a kangaroo hunt was organized in an attempt to capture it. They failed, and it seems mostly to have been a joke, but an anonymous photographer sent a Polaroid of a kangaroo to the local paper, supposedly taken in the area. It turned out to be a hoax, a photo of a stuffed wallaby someone had dragged out into a field. But sightings of the kangaroo persisted for months.

And sightings of kangaroos and wallabies don’t just happen in North America and the British Isles. Between 2003 and 2010, people in the Mayama mountain district of Osaki, Japan reported seeing a large brown animal with long ears, variously described as three to five feet tall, or one to 1.5 meters. Most sightings of the animal took place on roadsides when people were on their way to work or home from work.

No one has pictures of the kangaroo seen in Japan, though. No one has photos of the kangaroos reported in Chicago or any of the other sightings from 1899 on up through the new millennium. All those kangaroos were seen but never caught or photographed. A photo of a kangaroo was, however, once passed off as a photo of the Jersey Devil. According to a century of reports, the phantom kangaroos are just that, phantoms.

But these days, many people carry high-quality cameras with them everywhere, more commonly referred to as phones. And things started to change.

On January 3, 2005, a woman in Iowa County, Wisconsin called the sheriff’s department to say she’d seen a kangaroo hopping around on her horse farm. When the sheriff arrived, he was shocked to actually find a kangaroo, specifically a male red kangaroo. He knew better than to try to handcuff it, and instead got help to lure the kangaroo into a barn. It was captured safely and taken to the Henry Vilas Zoo, where it stayed until it died five years later. No one knows where it came from or why it was hopping around loose, but it was apparently fairly tame.

In 2013, some hunters took a video of a kangaroo in Oklahoma. I’ll put a link in the show notes, but it is 100% a kangaroo and not a blurry video that might be anything. A pet kangaroo named Lucy Sparkles had escaped in November of 2012 not too far away, but it turned out that the kangaroo caught on video wasn’t Lucy. It also wasn’t an escapee from a local exotic animal farm. It was a kangaroo from a man who kept kangaroos, which means there are way, way too many kangaroos in Oklahoma than I ever imagined.

Similarly, a man driving to work in July 2013 in North Salem, Connecticut got a few seconds of video of a kangaroo or wallaby bounding down the road and up someone’s driveway. In February of 2017, police officers on patrol spotted a wallaby in Somers, New York, which is believed to be a pet wallaby that escaped three years before in North Salem.

In other words, people really are seeing wallabies and kangaroos, not phantoms. Is it possible there are populations of either living in remote areas of North America, and that occasionally one wanders closer to a town or city and is seen? It’s possible, but not especially likely. Wallabies would be easy prey for wolves and coyotes, bears and cougars, and domestic dogs. We’d also probably have a lot of roadkill wallabies. Kangaroos would be more able to hold their own against predators, but are larger and therefore easier to spot. The climate in much of the United States also isn’t ideal for kangaroos or wallabies. Red kangaroos might be able to thrive in the arid and sparsely populated parts of the southwestern United States, but sightings of phantom kangaroos aren’t generally from those areas.

I’m pretty sure that the wallabies and kangaroos seen in North America, and probably most other places, are escaped pets. Wallabies in particular seem to be escape artists. So if you’re tempted to get an exotic pet and are looking at a wallaby, trust me: you’d be a lot happier with a dog.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast online at strangeanimalspodcast.com. We’re on Twitter at strangebeasties and have a facebook page at facebook.com/strangeanimalspodcast. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. If you like the podcast and want to help us out, leave us a rating and review on Apple Podcasts or whatever platform you listen on. We also have a Patreon if you’d like to support us that way.

Thanks for listening!