Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 14:58 — 15.2MB)

This week let’s learn about my nemesis (in Animal Crossing: New Horizons, at least), the tarantula!

Further reading:

Tarantulas inspire new structural color with the greatest viewing angle

My character in Animal Crossing (and the shirt I made her–yes, I know tarantulas are arachnids, not insects, but I think the shirt is funny):

Boy who is not afraid of a tarantula:

The Goliath birdeater and a hand. Not photoshopped:

The cobalt blue tarantula:

The Gooty sapphire ornamental:

The Singapore blue tarantula:

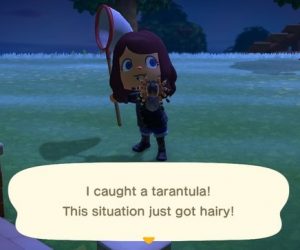

The painting by Maria Sibylla Merian that shows a tarantula eating a hummingbird (lower left):

The pinktoe tarantula that Merian painted:

The great horned baboon (not actually a baboon):

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

Just over two weeks ago I got a Nintendo Switch Lite and I’ve been playing Animal Crossing New Horizons a lot. I’m having a lot of fun with it, so let’s have a slightly Animal Crossing-themed episode and learn about my nemesis in the game, the tarantula.

A tarantula is a spider in the family Theraphosidae, and there are something like twelve hundred species. They live throughout much of the world, including most of the United States, Central and South America, Africa and some nearby parts of southern Europe and the Middle East, most of Asia, and Australia.

The tarantula is a predator, and while it can spin silk it doesn’t build a web to trap insects. It goes out and actively hunts its prey. It uses its silk to make a little nest that it hides in when it’s not hunting. Some species dig a burrow to live in but will line the burrow with silk to keep it from caving in and, let’s be honest, probably to make it more comfortable. The burrow of some species is relatively elaborate, for example those of the genus Brachypelma, which is from the Pacific coast of Mexico. Brachypelma’s burrow has two chambers, one reserved for molting its exoskeleton, one used for everyday activities like eating prey. Brachypelma usually sits at the entrance of its burrow and waits for a small animal to come near, at which point it jumps out and grabs it.

Many species of tarantula live in trees, but because they tend to be large and heavy spiders, falling out of a tree can easily kill a tarantula. But also because they’re large and heavy spiders, they can’t hold onto vertical surfaces the way most spiders do, using what’s called dynamic attachment. Most spiders have thousands of microscopic hairs at the end of their legs that allow it to hold onto surfaces more easily. But no matter what you learned from Spider-Man movies and comics, this doesn’t work very effectively for heavier animals, and many tarantulas are just too heavy. The tarantula does have two or three retractable claws at the end of its legs, but it’s also able to release tiny filaments of silk from its feet if it starts to slip, which anchors it in place.

Like other spiders, the tarantula has eight legs. It also has eight eyes, but the eyes are small and it doesn’t have very good vision. Most tarantulas are also covered with little hairs that make them appear fuzzy. These aren’t true hairs but setae [pronounced see-tee] made of chitin, although they do help keep a tarantula warm. They also help a tarantula sense the world around it with a specialized sense of touch. The setae are sensitive to the tiniest air currents and air vibrations, as well as chemical signatures.

Many species of tarantula have special setae called urticating spines that can be dislodged from the body easily. If a tarantula feels threatened, it will rub a leg against its abdomen, dislodging the urticating spines. The spines are fine and light so they float upward away from the spider on the tiny air currents made by the tarantula’s legs, and right into the face of whatever animal is threatening it. The spines are covered with microscopic barbs that latch onto whatever they touch. If that’s your face or hands, they are going to make your skin itch painfully, and if it happens to be your eyeball you might end up having to go to the eye doctor for an injured cornea. Scientists who study tarantulas usually wear eye protection.

One species of tarantula famous for its urticating spines also happens to be the heaviest spider known, and almost the biggest. It’s the Goliath birdeater, which I’m pretty sure we talked about in the spiders episode in October of 2018. Its leg span can be as much as a foot across, or 30 cm, and it can weigh as much as 6.2 ounces, or 175 grams. It’s brown or golden in color and lives in South America, especially in swampy parts of the Amazon rainforest. It’s nocturnal and mostly eats worms, large insects, other spiders, amphibians like frogs and toads, and occasionally other small animals like lizards and even snakes. And yes, every so often it will catch and eat a bird, but that’s rare. Birds are a lot harder to catch than worms, especially since the Goliath birdeater lives on the ground, not in trees. It’s considered a delicacy in northeastern South America, by the way. People eat it roasted. Apparently it tastes kind of like shrimp.

Most tarantulas from the Americas, known collectively as New World tarantulas, are mostly brown in color. Some have legs striped with rusty red, black, or white, but for the most part they’re all brown. But the Old World tarantulas found in the rest of the world are often more colorful, including many species that are blue. Not that slate gray color sometimes called blue but BRIGHT BLUE. The color isn’t caused by a pigment but by crystalline nanostructures in the exoskeleton, and researchers have recently found that different species of tarantula have evolved similar blue nanostructures independently—at least eight different times. Researchers have been studying the nanostructures and recently managed to replicate it with a nano-3D printer. Eventually they hope that the nanostructure color can replace toxic synthetic dyes for many materials. In addition to not being toxic, nanostructure colors don’t fade.

No one’s sure why so many tarantulas are blue, though. Remember that tarantulas don’t have very good eyesight so they probably don’t depend on color to attract a mate, at least as far as we know.

One blue tarantula is called the cobalt blue tarantula, which lives in the rainforests of southeast Asia. It spends most of its time in deep burrows except when it’s hunting. It has a legspan of about five inches, or 13 cm, and has blue legs and a gray body. Another is the Gooty sapphire ornamental, which is bright blue with a pattern of white on its body and legs. It’s from India, has a legspan of 8 inches, or 20 cm, and is critically threatened due to habitat loss. A third is the Singapore blue, which has a legspan of 9 inches, or 23 cm, and has bright blue legs and a brown or gold body. All these species, and many others, are bred in captivity as pets even though all tarantulas have venom that can cause painful reactions in humans.

Tarantula venom varies from species to species, and as with other venomous animals, researchers have been studying its venom to find potential medical uses, especially painkillers. The venom of some tarantulas targets nerve cells the same way that capsaicin does in hot chili peppers, resulting in a burning sensation. Australian tarantulas produce venom that contains a protein that is effective at killing insects if they eat it, not just if it’s injected, which has led to studies about using the protein to produce more eco-friendly insecticides for crops.

Results of a brand new study, published just a few weeks ago as this episode goes live, finds that the venom of the Chinese bird spider can be adapted to act as a strong pain reliever. It has similar results to morphine and related painkillers without side effects or risk of addiction. It still has to go through a number of clinical trials before it can be made into a drug for doctors to prescribe, but so far the results are promising.

Female tarantulas are usually a little larger than males, although the male may have longer legs. The female usually lays eggs once a year and guards her egg sac for six to eight weeks. She may also guard the babies after they hatch until they leave the nest. Male tarantulas typically don’t live very long compared to females, which can live for several decades in captivity—sometimes up to forty years.

The tarantula molts its exoskeleton periodically as it grows, several times a year for young spiders. Fully grown tarantulas may molt once a year or so. Molting is how a spider replaces lost or injured limbs and how it replaces its urticating spines.

So, in episode 90, about spiders, we talked about a lot of mystery spiders, including giant ones. It’s possible there are larger tarantula species out there than the Goliath birdeater, since new species of tarantula get discovered almost every year. But it’s not likely to be much larger, since as we also discussed in episode 90, the size of a spider or other terrestrial invertebrate is limited by its ability to absorb oxygen.

But there is another mystery associated with tarantulas that doesn’t have to do with their size, although it’s not a mystery that will keep you up at night. There’s a painting of tarantulas by Maria Sibylla Merian, a German artist who lived in the late 17th and early 18th centuries, that shows one tarantula eating a hummingbird. That’s actually how the Goliath birdeater and its close relations got the name birdeater. Merian painted tropical insects and other animals and plants, and unlike many of the artists of her day she was painstaking in her details and was a close observer of nature. She was also a leading entomologist back when that field was in its infancy and women weren’t supposed to do much of anything except have babies. She painted the birdeater tarantula during a trip to Dutch Surinam in South America, sometime between September 1699 and June 1701 when she returned home. It appeared in a book she published in 1705 with the help of her two grown daughters, and her paintings and notes were the first that many people in Europe had ever heard about animals and plants of the Americas. But while Merian’s paintings were meticulous in their details, no one was actually sure which tarantula she had painted.

The problem wasn’t her painting, but confusion about what species of tarantula actually live in northern South America. Carl Linnaeus described the first species of the genus Avicularia in 1758, but the tarantulas he studied, and the ones later assigned to Avicularia, were not actually all related. A few years ago, a team of spider experts in Brazil decided to figure it all out once and for all.

The team studied every specimen collected from the area, both newly collected and old ones in museums around the world. Previously, Avicularia had contained 49 species, but the team changed that to just 12—and three of those 12 were ones new to science. They separated the other species out into three new genera. One of the new species was named after Merian, Avicularia merianae.

The species Merian illustrated is the pinktoe tarantula, Avicularia avicularia, which is brown or black except for the tips of its legs, which are pinkish. Its venom is weak and its legspan is about six inches, or 15 cm. It lives in trees where it ambushes small animals, usually insects, although it will also scavenge already dead animals it finds. Researchers think this is probably the case with Merian’s painting of the tarantula eating a hummingbird, since the pinktoe is too small and weak to kill a hummingbird itself.

Some species of tarantula makes a sort of soft hissing or rattling sound if it feels threatened, called stridulating. Some other spiders and other animals make a similar noise. The tarantula rubs the hairs of its legs together to produce the noise, which sounds like this:

[tarantula stridulating sound]

The tarantula making that sound is called the great horned baboon, which is from Zimbabwe and Mozambique in southern Africa and is not a baboon but a spider. Its legspan is about six inches, or 15 cm, and it’s a very pretty black or gray with a white pattern over most of its body and legs, and a brown or tan pattern on its abdomen. But the most remarkable thing about it is the so-called horn. This is a black horn-like structure that grows from the spider’s carapace. No one is sure what the horn is for. No one except the tarantula, that is.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast online at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. If you like the podcast and want to help us out, leave a rating and review on Apple Podcasts or wherever you listen to podcasts. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us that way.

Thanks for listening!