Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 10:26 — 11.6MB)

Thanks to Mila for suggesting one of our topics today!

Further reading:

The mystery of the ‘missing’ giant millipede

Never-before-seen head of prehistoric, car-size ‘millipede’ solves evolutionary mystery

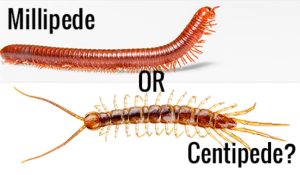

A centipede compared to a millipede:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

Let’s finish invertebrate August this year with two arthropods. One is a suggestion from Mila and the other is a scientific mystery that was solved by a recent discovery, at least partially.

Mila suggested we learn about centipedes, and the last time we talked about those animals was in episode 100. That’s because centipedes are supposed to have 100 legs.

But do centipedes actually have 100 legs? They don’t. Different species of centipede have different numbers of legs, from only 30 to something like 300. Like other arthropods, the centipede has to molt its exoskeleton to grow larger. When it does, some species grow more segments and legs. Others hatch with all the segments and legs they’ll ever have.

A centipede’s body is flattened and made up of segments, a different number of segments depending on the centipede’s species, but at least 15. Each segment has a pair of legs except for the last two, which have no legs. The first segment’s legs project forward and end in sharp claws with venom glands. These legs are called forcipules, and they actually look like pincers. No other animal has forcipules, only centipedes. The centipede uses its forcipules to capture and hold prey, and to defend itself from potential predators. A centipede pinch can be painful but not dangerous unless you’re also allergic to bees, in which case you might have an allergic reaction to a big centipede’s venom. Small centipedes can’t pinch hard enough to break a human’s skin.

A centipede’s last pair of legs points backwards and sometimes look like tail stingers, but they’re just modified legs that act as sensory antennae. Each pair of a centipede’s legs is a little longer than the pair in front of it, which helps keep the legs from bumping into each other when the centipede walks.

The centipede lives throughout the world, even in the Arctic and in deserts, but it needs a moist environment so it won’t dry out. It likes rotten wood, leaf litter, soil, especially soil under stones, and basements. Some centipedes have no eyes at all, many have eyes that can only sense light and dark, and some have relatively sophisticated compound eyes. Most centipedes are nocturnal.

The largest centipedes alive today belong to the genus Scolopendra. This genus includes the Amazonian giant centipede, which can grow over a foot long, or 30 cm. It’s reddish or black with yellow bands on the legs, and lives in parts of South America and the Caribbean. It eats insects, spiders–including tarantulas, frogs and other amphibians, small snakes and lizards, birds, and small mammals like mice. It’s even been known to catch bats in midair by hanging down from cave ceilings and grabbing the bat as it flies by.

Some people think that the Amazonian giant centipede is the longest in the world, but this isn’t actually the case. Its close relation, the Galapagos centipede, can grow 17 inches long, or 43 cm, and is black with red legs.

But if you think that’s big, wait until you hear about the other animal we’re discussing today. It’s called Arthropleura and it lived in what is now Europe and North America between about 344 and 292 million years ago.

Before we talk about it, though, we need to learn a little about the millipede. Millipedes are related to centipedes and share a lot of physical characteristics, like a segmented body and a lot of legs. The word millipede means one thousand feet, but millipedes can have anywhere from 36 to 1,306 legs. That is a lot of legs. It’s probably too many legs. The millipede with 1,306 legs is Eumillipes persephone, found in western Australia and only described in 2021. It lives deep underground in forested areas, where it probably eats fungus that grows on tree roots. It’s long and thin with short legs and no eyes. It’s only about 1 mm in diameter, but can grow nearly 4 inches long, or almost 10 cm.

Millipedes mostly eat decaying plant material and are generally chunkier-looking than centipedes. They have two pairs of legs per segment instead of just one, with the legs attached on the underside of the segment instead of on the sides. A millipede usually has short, strong antennae that it uses to poke around in soil and decaying leaves. It can’t pinch, sting, or bite, although some species can secrete a toxic liquid that also smells terrible. Mostly if it feels threatened, a millipede will curl up and hope the potential predator will leave it alone.

The biggest millipede alive today is probably the giant African millipede, which can grow over 13 inches long, or almost 34 cm, but because millipedes are common throughout the world and are often hard for scientists to find, there may very well be much larger millipedes out there that we just don’t know about.

As an example, in 1897 scientists discovered a new species of giant millipede in Madagascar and named it Spirostreptus sculptus. One specimen found was almost 11 inches long, or over 27 cm. But after that, no scientist saw the millipede again—until 2023, when a scientific expedition looking for lost species rediscovered it, along with 20 other species of animal. It turns out that the millipede isn’t even uncommon in the area, so the local people probably knew all about it.

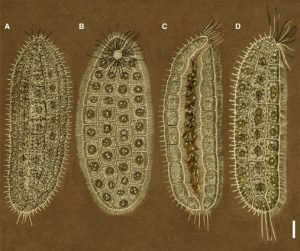

But Arthropleura was way bigger than any millipede or centipede alive today. It could grow at least 8 ½ feet long, or 2.6 meters, and possibly longer. It probably weighed over 100 lbs, or 45 kg. We have plenty of fossilized specimens, but not one of them has an intact head. Then scientists discovered two beautifully preserved juvenile specimens in France, and CT scans in 2024 revealed that both specimens had nearly complete heads.

The big question about Arthropleura was whether it was more closely related to millipedes or centipedes, or if it was something very different. Without a head to study, no one could answer that question with any confidence, although a lot of scientists had definite opinions one way or another. Studies of the head scans determined that Arthropleura was indeed more closely related to modern millipedes—but naturally, since it lived so long ago, it also had a lot of traits more common in centipedes today. It also had something not found in either animal, eyes on little stalks.

There are still lots of mysteries surrounding Arthropleura. For instance, what did it eat? Because of its size, scientists initially thought it might be a predator. Now that we know it was more closely related to the millipede than the centipede, scientists think it might have eaten like a millipede too. That would mean it mostly ate decaying vegetation, but we don’t know for sure. We also don’t know if it could swim or not. We have a lot of Arthropleura tracks that seem to be made along the water’s edge, so some scientists hypothesize that it could swim or at least spent part of its time in the water. Other scientists point out that Arthropleura didn’t have gills or any other way to absorb oxygen while in the water, so it was more likely to be fully terrestrial. The first set of scientists sometimes comes back and argues that we don’t actually know how Arthropleura breathed or even why it was able to grow so large, and maybe it really did have gills. A third group of scientists then has to come in and say, hey, everyone calm down, maybe the next specimen we find will show evidence of both lungs and gills, and it spent part of its time on land and part in shallow water, so there’s no need to argue. And then they all go for pizza and remember that they really love arthropods, and isn’t Arthropleura the coolest arthropod of all?

At least, I think that’s how it works among scientists. And Arthropleura is really cool.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us for as little as one dollar a month and get monthly bonus episodes.

Thanks for listening!