Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 10:32 — 12.7MB)

Thanks to Tobey and Anbo for their suggestions this week! We’re going to learn about some giant invertebrates!

Further reading:

The Invasive Giant African Land Snail Has Been Spotted in Florida

A very big shell:

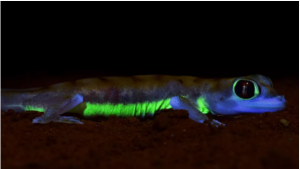

The giant African snail is pretty darn giant [photo from article linked above]:

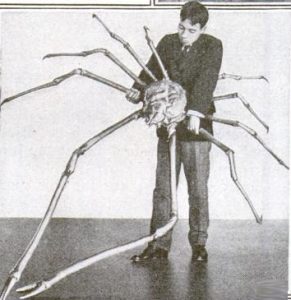

The largest giant spider crab ever measured, and a person:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

This week we’re going to learn about some giant invertebrates, suggested by Tobey and Anbo. Maybe they’re not as big as dinosaurs or whales, but they’re surprisingly big compared to most invertebrates.

Let’s start with Tobey’s suggestion, about a big gastropod. Gastropods include slugs and snails, and while Tobey suggested the African trumpet snail specifically, I couldn’t figure out which species of snail it is. But it did lead me to learning a lot about some really big snails.

The very biggest snail known to be alive today is called the Australian trumpet snail, Syrinx aruanus. This isn’t the kind of snail you’d find in your garden, though. It’s a sea snail that lives in shallow water off the coast of northern Australia, around Papua New Guinea, and other nearby areas. It has a coiled shell that’s referred to as spindle-shaped, because the coils form a point like the spindle of a tower. It’s a pretty common shape for sea snails and you’ve undoubtedly seen this kind of seashell before if you’ve spent any time on the beach. But unless you live in the places where the Australian trumpet lives, you probably haven’t seen a seashell this size. The Australian trumpet’s shell can grow up to three feet long, or 91 cm. Not only is this a huge shell, the snail itself is really heavy. It can weigh as much as 31 lbs, or 14 kg, which is as heavy as a good-sized dog.

The snail eats worms, but not just any old worms. If you remember episode 289, you might remember that Australia is home to the giant beach worm, a polychaete worm that burrows in the sand between high and low tide marks. It can grow as much as 8 feet long, or 2.4 meters, and probably longer. Well, that’s the type of worm the Australian trumpet likes to eat, along with other worms. The snail extends a proboscis into the worm’s burrow to reach the worm, but although I’ve tried to find out how it actually captures the worm in order to eat it, this seems to be a mystery. Like other gastropods, the Australian trumpet eats by scraping pieces of food into its mouth using a radula. That’s a tongue-like structure studded with tiny sharp teeth, and the Australian trumpet has a formidable radula. Some other sea snails, especially cone snails, are able to paralyze or outright kill prey by injecting it with venom via a proboscis, so it’s possible the Australian trumpet does too. The Australian trumpet is related to cone snails, although not very closely.

Obviously, we know very little about the Australian trumpet, even though it’s not hard to find. The trouble is that its an edible snail to humans and humans also really like those big shells and will pay a lot for them. In some areas people have hunted the snail to extinction, but we don’t even know how common it is overall to know if it’s endangered or not.

Tobey may have been referring to the giant African snail, which is probably the largest living land snail known. There are several snails that share the name “giant African snail,” and they’re all big, but the biggest is Lissachatina fulica. It can grow more than 8 inches long, or 20 cm, and its conical shell is usually brown and white with pretty banding in some of the whorls. It looks more like the shell of a sea snail than a land snail, but the shell is incredibly tough.

The giant African snail is an invasive species in many areas. Not only will it eat plants down to nothing, it will also eat stucco and concrete for the minerals they contain. It even eats sand, cardboard, certain rocks, bones, and sometimes other African giant snails, presumably when it runs out of trees and houses to eat. It can spread diseases to plants, animals, and humans, which is a problem since it’s also edible.

Like many snails, the African giant snail is a simultaneous hermaphrodite, meaning it can produce both sperm and eggs. It can’t self-fertilize its own eggs, but after mating a snail can keep any unused sperm alive in its body for up to two years, using it to fertilize eggs during that whole time, and it can lay up to 200 eggs five or six times a year. In other words, it only takes a single snail to produce a wasteland of invasive snails in a very short amount of time.

In June 2023, some African giant snails were found near Miami, Florida and officials placed the whole area under agricultural quarantine. That means no one can move any soil or plants out of the area without permission, since that could cause the snails to spread to other places. Meanwhile, officials are working to eradicate the snails. Other parts of Florida are also under the same quarantine after the snails were found the year before. Sometimes when people go on vacation in the Caribbean they bring back garden plants, without realizing that the soil in the pot contains giant African snail eggs, because the giant African snail is also an invasive species throughout the Caribbean.

Next, Anbo wanted to learn about the giant spider crab, also called the Japanese spider crab because it lives in the Pacific Ocean around Japan. It is indeed a type of crab, which is a crustacean, which is an arthropod, and it has the largest legspan of any arthropod known. Its body can grow 16 inches across, or 40 cm, and it can weigh as much as 42 pounds, or 19 kg, which is almost as big as the biggest lobster. But its legs are really really really long. Really long! It can have a legspan of 12 feet across, or 3.7 meters! That includes the claws at the end of its front legs. Most individual crabs are much smaller, but since crustaceans continue to grow throughout their lives, and the giant spider crab can probably live to be 100 years old, there’s no reason why some crabs couldn’t be even bigger than 12 feet across. Its long legs are delicate, though, and it’s rare to find an old crab that hasn’t had an injury to at least one leg.

The giant spider crab is orange with white spots, sort of like a koi fish but in crab form. Its carapace is also bumpy and spiky. You wouldn’t think a crab this size would need to worry about predators, but it’s actually eaten by large octopuses. The crab sticks small organisms like sponges and kelp to its carapace to help camouflage it.

The giant spider crab is considered a delicacy in some places, which has led to overfishing. It’s now protected in Japan, where people are only allowed to catch the crabs during part of the year. This allows the crabs to safely mate and lay eggs.

There’s another species called the European spider crab that has long legs, but it’s nowhere near the size of the giant spider crab. Its carapace width is barely 8 ½ inches across, or 22 cm, and its legs are about the same length. Remember that the giant spider crab’s legs can be up to six feet long each, or 1.8 meters. While the European spider crab does resemble the giant spider crab in many ways, it’s actually not closely related to it. They two species belong to separate families.

The giant spider crab spends most of its time in deep water, although in mating season it will come into shallower water. It uses its long legs to walk around on the sea floor, searching for food. It’s an omnivore that eats pretty much anything it can find, including plants, dead animals, and algae, but it will also use its claws to open mollusk shells and eat the animals inside. It prefers rocky areas of the sea floor, since its bumpy carapace blends in well among rocks.

Scientists report that the giant spider crab is mostly good-natured, even though it looks scary. Some big aquariums keep giant spider crabs, and the aquarium workers say the same thing. But it does have strong claws, and if it feels threatened it can seriously injure divers. I shouldn’t need to remind you not to pester a crab with a 12-foot legspan.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us for as little as one dollar a month and get monthly bonus episodes.

Thanks for listening!