Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 13:32 — 10.7MB)

Let’s learn about the great auk this week, along with some lookalike birds, penguins!

A great auk, as painted by Audubon:

A razorbill, the auk’s closest living relative:

A fairy penguin, so tiny:

An emperor penguin, so big:

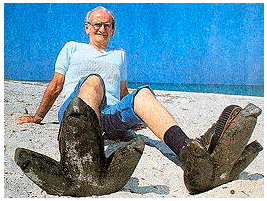

Tony Signorini wearing his Hoax Shoes:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

This week’s topic is one I’ve had on my list to cover for some time, and a couple of people whose names I forgot to write down also suggested. It’s the great auk, and while we’re at it we’re going to learn about penguins too.

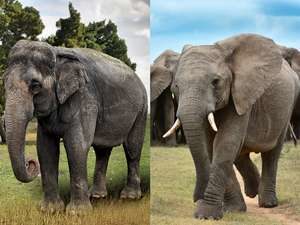

Picture this bird in your mind. It’s big, close to three feet tall, or 85 cm, black with a white belly and white spots over the eyes during breeding season. It has a big dark bill and eats fish and crustaceans. Its feet are webbed and it’s flightless, because instead of flying, it swims, fast and agile in the water but clumsy on land. It’s social, nesting in big colonies and laying one egg, which both parents incubate. Both parents also help feed the chick when it hatches. Pairs mate for life. And it lives in cold waters of the North Atlantic from eastern Canada to Greenland and Iceland over to the western coast of Europe.

Wait a minute, you say, knowledgeably, because you know a thing or two about penguins. Penguins live in the southern hemisphere. What is going on??

The great auk is going on, my friend. And while the similarities between the great auk and the various species of penguin are striking, they’re not closely related at all. The great auk’s scientific name is Pinguinus impennis, and it was sometimes called a penguin, but the penguin is named after the auk because of the similarities between the two. The most obvious difference between the great auk and the penguin is the bill. Penguins have relatively small, sharp bills, but great auk bills were much larger and heavier, grooved and with a hook at the end.

So is the great auk still around? I sure made it sound like it was still around, didn’t I? Unfortunately, no. The last known great auks were killed on June 3, 1844, with a few sightings in the years after. The last probable sighting of a great auk was in 1852. But it had been a really common bird for a long time. What was it like, and what happened to it?

The great auk lived almost its whole life in the water. It only came out to breed and lay eggs, one egg per couple. Its babies grew fast and took to the sea when only a few weeks old, but the parents continued to feed their baby and care for it in the water. Sometimes a young auk would ride on its parent’s back as it swam.

It was incredibly at home in the water. It could hold its breath for something like 15 minutes, could dive deeply and swim so quickly that it could shoot up out of the water to land on ledges well above the ocean’s surface. Because of its swimming ability and its size, it wasn’t scared of very many animals. Polar bears, orcas, and a few other large predators sometimes ate it, but its main predator was these aggressive apes called humans. Maybe you’ve heard of them.

People killed the great auk for food, for feathers, and to use its skin and bones as decorative items. Its remains have been found at Neandertal campsites too. And because it was a large, plentiful bird, people hunted it and hunted it and hunted it. The great auk was already nearly extinct around Europe by the mid 16th century, since it was killed for its down, which was used to stuff pillows. Auk eggs were also collected for food. And as the bird became rarer, museums decided they had better get specimens while they could. The last great auks were killed so they could be stuffed and mounted.

So if there’s a great auk, is there a lesser auk? There is, and it’s still around! The little auk is only about 8 inches long, or 21 cm, but unlike the great auk it can fly. It eats small fish, crustaceans, and invertebrates. But the razorbill is a much closer relative.

The razorbill has a lot in common with the great auk but it’s much smaller, only up to 17 inches high, or 43 cm. It also flies. It was once hunted for its meat and feathers, but after it was protected in 1917 its numbers rebounded. Its primary problem these days is pollution of its breeding sites.

There was once a group of even bigger auks than the great auk. The Mancallinae were flightless and lived on the western North American coast. The largest species was Miomancalla howardae, which went extinct almost 5 million years ago. It stood more than three feet tall, or 1 meter, but was heavier and bulkier than the great auk.

As for penguins, fortunately, they’re still around although they’re all threatened due to pollution, habitat loss, and climate change. They have no natural fear of humans, probably because they have no land predators in Antarctica. Polar bears and walruses live near the Arctic, which is in the northern hemisphere, and sled dogs aren’t allowed in Antarctica. I did not know that until just now. I mean, I knew the polar bears and walruses part, not the dog part.

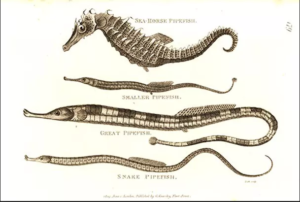

The smallest penguin is called the fairy penguin, and it’s only 16 inches tall at most, or 40 cm. It lives off the coast of Australia, New Zealand, and Chile. Its head is blue, which is why it’s also called the little blue penguin. Like other penguin species, it eats fish, cephalopods like squid, and crustaceans such as krill. It especially likes jellyfish.

The largest penguin is, of course, the emperor penguin, famous from March of the Penguins. If you haven’t seen that documentary, you’ll learn lots of things about emperor penguins and will also cry. The march in the title is the migration the penguins take to breeding colonies, where they may walk over the ice up to 75 miles, or 120 km. Penguins are not very good at walking, either. Once they’ve reached the breeding colony, each female lays one small egg, which has a thick shell. The male has a brood pouch to keep the egg warm, basically a fold in his skin above his feet. The egg sits on his feet with the rest of it in the brood pouch. After that, the female leaves to go hunting, because making her egg takes a lot out of her and she needs to replace her body reserves. The male incubates the egg by himself.

It gets really cold in the Antarctic during winter. Seriously, really cold, as cold as -40 degrees. Negative 40 is the same temperature in Celcius and Fahrenheit, which is kind of neat. Emperor penguins choose breeding colonies that are protected from the wind as much as possible, but they still have to deal with wind gusts of 90 mph, or 145 km per hour. To withstand the cold, penguins have dense feathers and a thick layer of blubber. Males huddle together for warmth, with every penguin getting a turn to be on the inside of the crowd where it’s warmer, and spending their fair share of time on the edges of the crowd where it’s colder. During the two months after eggs are laid, males don’t eat anything. When his egg hatches, the male feeds the baby with crop milk, which you may remember from episode 19, about the dodo. Crop milk isn’t milk at all, but a nutritious substance formed from a parent bird’s esophagus. Only male emperor penguins produce crop milk.

A short time after the eggs hatch, female emperor penguins return from hunting. The female takes over care of the chick, feeding it with regurgitated food, so the male can leave to go hunting. Males and females trade off in this way for a couple of months, until the chick is old enough and big enough to be left alone for stretches.

The emperor penguin lives in Antarctica and can grow over four feet tall, or 130 cm, which is just ridiculously large. It can also weigh up to 100 lbs, or 45 kg. In other words, it’s as big as a small person and much bigger even than the great auk was. It’s a strong swimmer and can dive deeply—the deepest recorded dive was well over 1800 feet, or 565 meters, which is whale diving depth.

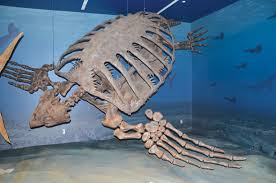

But the emperor penguin isn’t the biggest penguin that ever lived. Anthropornis went extinct around 33 million years ago, and it was a penguin that was actually the height of a tall human, some six feet tall, or 1.8 meters. It lived off the coast of what is now New Zealand and Antarctica. The New Zealand giant penguin probably lived around the same time as Anthropornis, and was around five feet tall, or 1.6 meters, but probably weighed more. Neither were direct ancestors of modern penguins, but they probably looked and acted very similar. Just, you know, enormous.

A newly discovered giant penguin, also from New Zealand, lived much earlier than the others. It was already almost five feet tall, or 1.5 meters, and well adapted to the water 61 million years ago. Remember that the Cretaceous-Paleogene extinction event occurred around 66 million years ago. Some researchers hypothesize that penguins had already begun evolving when dinosaurs were still alive, and that they survived the extinction event.

Another extinct penguin, one that was more directly related to modern penguins, lived around South America some 36 million years ago. Icadyptes was almost as tall as the other giant penguins and had a bill that was much longer and pointier than modern penguin bills, more like a heron’s bill. It also lived in much warmer waters than most modern penguins.

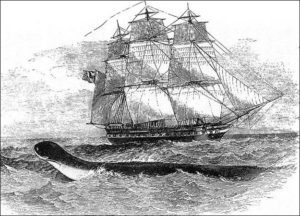

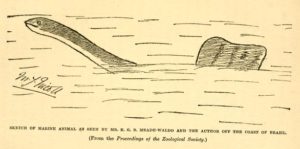

Back in the 1920s and 30s, when fossils of giant penguins were first described, they caught the public’s imagination. Giant penguins appeared in science fiction of the day, including Jules Verne and HP Lovecraft. Starting in February of 1948, people in Florida began finding enormous three-toed tracks in sand on a few beaches and along the Suwannee River. The footprints were over a foot long, or 35 cm, and the animal’s stride was measured at between 4 and 6 feet long, or 1.2 to 1.8 meters. Cryptozoologist Ivan T. Sanderson examined the tracks in November of 1948. After weeks of study he reported gravely that they’d been made by a penguin 15 feet tall, or 4.5 meters.

It turns out, though, that it was all a hoax. Two men named Tony Signorini and Al Williams had made gigantic iron feet they could wear as great big shoes, and walked in the sand overnight leaving trails of monstrous tracks ready to be discovered by beachcombers. They actually intended the tracks to be taken for dinosaur or sea monster footprints, but a giant penguin was even better. Each foot weighed about 30 lbs, or 13.5 kg, and Signorini used the weight to swing along in a sort of controlled bound that made his stride remarkably long without too much effort. Williams died in 1969 but Signorini didn’t come clean about the hoax until 1988.

He still has the feet.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast online at strangeanimalspodcast.com. We’re on Twitter at strangebeasties and have a facebook page at facebook.com/strangeanimalspodcast. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. If you like the podcast and want to help us out, leave us a rating and review on Apple Podcasts or whatever platform you listen on. We also have a Patreon if you’d like to support us that way.

Thanks for listening!