Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 20:47 — 16.6MB)

Subscribe: | More

This week we’re going to find out about the biggest turtles that ever lived! Spoiler: one of them is alive right now, swimming around eating jellyfish.

A green sea turtle. These guys are adorable:

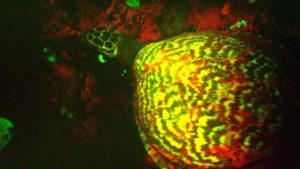

A hawkbill glowing like a neon sign!

The majestic and enormous leatherback:

Bebe leatherback. LET ME GOW

Seriously, how are baby sea turtles so darn cute?

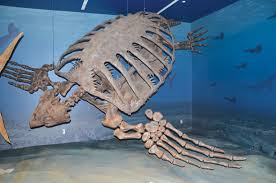

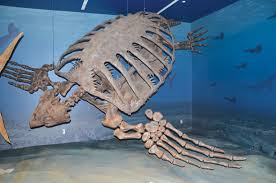

Archelon was a big tortle:

Further reading:

This is a link to a pdf of that “Historicity of Sea Turtles Misidentified as Sea Monsters” article

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

This week we’re back in the sea, but not the deep sea this time, because we’re looking at marine turtles!

The oldest known turtle ancestor lived around 220 million years ago, but it wouldn’t have looked a whole lot like a modern turtle. For one thing, it had teeth instead of a bill. It resembled a lizard with wide ribs that protected its belly. It lived in the ocean, probably in shallow inlets and bays, but it may have also spent part of its time on land. Some researchers think it may have had at least a partial shell formed from extensions of its backbone, but that this didn’t fossilize in the three specimens we have.

The oldest sea turtle fossil found so far has been dated to 120 million years old. It was seven feet long, or 2 meters, and already showed a lot of the adaptations that modern sea turtles have. Researchers think it was closely related to the green sea turtle and the hawksbill sea turtle.

Seven species of sea turtle are alive today. They all have streamlined shells and flippers instead of feet. They all breathe air, but they have big lungs and can stay underwater for a long time, up to about an hour while hunting, several hours when asleep or resting. Like whales, they surface and empty their lungs, then take one huge breath. They can see well underwater but can probably only hear low-frequency sounds.

Sea turtles have a special tear gland that produces tears with high salt concentration, to release excess salt from the body that comes from swallowing sea water. They migrate long distances to lay eggs, thousands of miles for some species and populations, and usually return to the same beach where they were hatched. Female sea turtles come ashore to lay their eggs in sand, but the males of most species never come ashore. The exception is the green sea turtle, which sometimes comes ashore just to bask in the sun. Once the babies hatch, they head to the sea and take off, swimming far past the continental shelf where there are fewer predators. They live around rafts of floating seaweed call sargassum, which protects them and attracts the tiny prey they eat.

Six of the extant sea turtles are relatively small. Not small compared to regular turtles, small compared to the seventh living sea turtle, the leatherback. More about that one in a minute. The other six are the green, loggerhead, hawksbill, Kemp’s ridley and Olive ridley, and the flatback.

Let’s start with the green sea turtle, since I just mentioned it. Its shell is not always green. It can be brown or even black depending on where it spends most of its life. Green turtles that live in colder areas of the Pacific have darker shells, which probably helps them stay warm by absorbing more heat from sunlight. Young turtles have darker shells than old turtles for the same reason.

The green sea turtle can grow up to five feet long, or 1.5 meters, can live some 80 years, and mostly eats plants, especially seagrass, although babies eat small animals like worms, jellyfish, and fish eggs. A recent satellite tracking study of green sea turtles in the Indian Ocean tracked the turtles to a huge underwater seagrass meadow that no human realized existed until then. The meadows were farther underwater than the ones researchers knew about, up to 95 feet deep, or 29 meters. Researchers think the seagrass can grow at these depths because the water is so clear in the area, which means more light for the plants.

Unlike the green sea turtle, which lives throughout much of the world’s oceans, the flatback sea turtle is only found around Australia. It’s greenish or grayish and only grows around 3 feet long, or 95 cm, and eats invertebrates of various kinds, including jellyfish, shrimp, and sea cucumbers. It stays near shore in shallow water and doesn’t migrate, so it’s mostly safe from getting tangled in commercial fishing nets that kill a lot of other sea turtle species.

The smallest sea turtle is the olive ridley, which only grows around two feet long, or 60 cm. Its shell is roughly heart-shaped and is usually olive green. It mostly lives in tropical waters and is the most common sea turtle of all the living species, but getting rarer. It likes warm, shallow water and eats small animals like snails, jellyfish, and sea urchins.

Kemp’s ridley sea turtle is closely related to the olive ridley, and is not much larger. It grows to around 28 inches long, or 70 cm, and eats the same things as the olive ridley. It also likes the same warm, shallow waters, but it nests exclusively along the Gulf Coast of North America. Oil spills in the Gulf have killed so many turtles that the species is now listed as critically endangered. Conservationists sometimes remove eggs to safer, cleaner beaches where babies are more likely to hatch and survive. Besides oil spills and other types of pollution, Kemp’s ridley sea turtles are often killed when they get tangled in shrimp nets and drown. Fortunately, shrimp trawlers in the Gulf now use turtle excluders, which help keep turtles from getting tangled.

The hawksbill sea turtle grows to around three feet long, or 1 meter, and lives around tropical reefs. It has a more pointed, hooked beak than other sea turtles, which gives it its name. You might think it eats fish or something with a beak like that, but mostly it eats jellyfish and sea sponges. It especially likes the sea sponges, some of which are lethally toxic to most other animals. It also doesn’t have a problem eating even extremely stingy jellies and jelly-like animals like the Portuguese man-o-war. The hawkbill’s head is armored so the stings don’t bother it, although it does close its eyes while it chomps down on jellies. People used to kill hawksbill sea turtles for their multicolored shells, but don’t eat them. Its meat can be toxic due to the toxins it ingests.

The hawksbill is also biofluorescent! Researchers only found this out by accident in 2015, when a team studying biofluorescent animals in the Solomon Islands saw and filmed a hawksbill glowing like a UFO with neon green and red light. Researchers still don’t know why and how the hawksbill glows. They think the red color may be emitted by certain algae that grow on hawksbill shells, but the green appears to be emitted by the turtle itself. Since the hawksbill lives mostly around coral reefs, where many animals biofluoresce, researchers hypothesize it might be a way for the turtle to blend in. If everyone’s glowing, the big turtle-shaped spot that isn’t glowing would give it away. Then again, since male turtles glow more brightly than females, researchers also think it may be a way to attract mates.

Finally, the loggerhead sea turtle grows to a little longer than three feet, or 95 cm, and its shell is usually reddish-brown. It lives throughout the world’s oceans and while it nests in a lot of places, many loggerheads lay their eggs on Florida beaches. It eats invertebrates like bivalves and sponges, barnacles and jellyfish, starfish, plants, and lots of other things, including baby turtles. Its jaws are powerful and it has scales on its front flippers that stick out a little, called pseudoclaws, which allow it to manipulate its food or tear it into smaller pieces.

All sea turtles are endangered and are protected worldwide, although some countries enforce the protection more than others. Some people still eat sea turtles and their eggs, even though both can contain bacteria and toxic metals that make people sick. But mostly it’s habitat loss, pollution, and fishing nets and longlines that kill turtles.

People want to build houses on the beach, or drive their cars on the beach, and that destroys the habitat female turtles need to lay their eggs. Turtles also get stuck in fishing equipment and drown. And there’s so much plastic floating around in the sea that all sorts of animals are affected, not just turtles. A floating plastic bag or popped balloon looks like a jellyfish to a sea turtle that doesn’t know what plastic is. A turtle can eat so much plastic that its digestive system becomes clogged and it dies. One easy way you can help is to remember your reusable bag when you go shopping. The fewer plastic bags that are made and used, the fewer will find their way into the ocean. Some countries have banned plastic shopping bags completely.

Now let’s talk about the leatherback turtle. It’s much bigger than the others and not very closely related to them. It can grow some nine feet long, or 3 meters, and instead of having a hard shell like other sea turtles, its carapace is covered with tough, leathery skin studded with tiny osteoderms. Seven raised ridges on the carapace run from head to tail and make the turtle more stable in the water, a good thing because leatherbacks migrate thousands of miles every year. Not only is the leatherback the biggest and heaviest turtle alive today by far, it’s the heaviest living reptile that isn’t a crocodile. It has huge front flippers, is much more streamlined even than other sea turtles, and has a number of interesting adaptations to life in the open ocean.

The leatherback lives throughout the world, from warm tropical oceans up into the Arctic Circle. It mostly eats jellyfish, so it goes where the jellyfish go, which is everywhere. It also eats other soft-bodied animals like squid. To help it swallow slippery, soft food when it doesn’t have the crushing plates that other sea turtles have, the leatherback’s throat is full of backwards-pointing spines. What goes down, will not come back up, which is great when the turtle swallows a jellyfish, not so great when it swallows a plastic bag.

The leatherback can dive as deep as 4,200 feet, or almost 1,300 meters. Even most whales don’t dive that deep. But it’s a reptile, so how does it manage to survive in such cold water, whether in the Arctic Ocean or nearly a mile below the water’s surface?

The leatherback’s metabolic rate is high to start with, and it swims almost constantly. Its muscles generate heat as they work, which keeps the turtle’s body warmer than the surrounding water, as much as 30 degrees Fahrenheit warmer, or 18 degrees Celsius. Its flippers and throat also use a system called countercurrent heat exchange, where blood that has been chilled by outside temperatures returns to the heart in veins that surround arteries containing warm blood flowing from the heart. By the time the cool blood reaches the heart, it’s been warmed by the arterial blood. This keeps heat inside the body’s core.

Unlike other sea turtle species, leatherbacks don’t necessarily return to the same beach where they were hatched to lay their eggs. Females usually nest every two or three years and lay about 100 eggs per nest. No one is sure how long leatherbacks live, but it may be a very long time. Most turtles have long lifespans, and many sea turtle species don’t even reach maturity until they’re a couple of decades old.

One interesting thing about sea turtles, which is also true of many other reptiles, is that the temperature of the egg determines whether the baby turtle will develop into a male or female. Cooler temperatures produce mostly male babies, warmer temperatures produce mostly female babies. This is pretty neat, until you remember that the global temperature is creeping up. A new study of sea turtles around Australia’s northern Great Barrier Reef found that almost all baby turtles hatching there are now female—up to 99.1% of all babies hatched. Another study found the same results in sea turtle nests in Florida, where 97 to 100% of all babies are female. The studies also found that the amount of water in the nest’s sand also contributes to whether babies are male or female, with drier nests producing more females. Researchers are considering incubating some nests in climate-controlled rookeries to ensure that enough males hatch and survive to produce the next generation.

So those are the seven types of sea turtle alive today. Now let’s talk about an extinct sea turtle, a relative of the leatherback. This is archelon, and it was huge.

Archelon was the biggest turtle that has ever lived, as far as we know. The first fossil archelon was discovered in 1895 in South Dakota, in rocks that were around 75 million years old. The biggest archelon fossil ever found came from the same area, and measures 13 feet long, or 4 meters. It’s even broader from flipper to flipper, some 16 feet wide, or 5 meters. It lived in the shallow sea that covered central North America during the Cretaceous, called the Western Interior Seaway. I like that name. Its shell was leathery and probably flexible like the leatherback’s, but unlike the leatherback, it wasn’t teardrop shaped. In fact, it was very round. Since it lived at the same time as mosasaurs, its wide shell may have kept it from being swallowed by predators. It probably ate squid and jellyfish like the leatherback, and researchers think it was probably a slow swimmer. It went extinct at the same time as the dinosaurs, but fortunately its smaller relations survived.

We don’t know if that 13-foot-long archelon was an unusually large specimen, an average specimen, or a small specimen. It was probably on the large size, but it’s a good bet that there were larger individuals swimming around 75 million years ago. We don’t know if leatherbacks occasionally get bigger than nine feet long, for that matter. But we do have reports of sea turtles that are much, much bigger than any sea turtles known.

In August of 2008, a 14-year-old boy snorkeling in Hawaii reported swimming above a sea turtle that was resting on the bottom of a lagoon. He estimated the turtle was eight to ten feet across with a round shell. At the time he didn’t realize that was unusual. He also reported seeing a geometric pattern on the shell, which is not a feature of the leatherback or archelon but is present in other sea turtles. So if his estimation of size is correct, he saw a sea turtle far bigger than any living today.

In 1833, a schooner off the coast of Newfoundland came across what they thought was an overturned boat. When the crew investigated, they discovered it wasn’t a boat at all but an enormous leatherback turtle, which they reported was 40 feet long, or 12 meters.

Many sea serpent sightings may actually be misidentifications of sea turtles. Sea turtles do have relatively long necks which they can and do raise out of the water. A long neck with a small head sticking out of the water, with a hump behind it, describes a lot of sea serpent reports. It’s also possible that some sea serpent reports are actually sightings of sea turtles entangled with fishing nets and other debris that the turtle drags with it as it swims, which may look like a long snake-like tail behind a humped body.

For instance, in 1934 some fishermen off the coast of Queensland, Australia spotted what they thought was a sea serpent. I’ll quote the description, which is from an article with the lengthy title of “Historicity of Sea Turtles Misidentified as Sea Monsters: A Case for the Early Entanglement of Marine Chelonians in Pre-plastic Fishing Nets and Maritime Debris” by Robert France. I’ll put a link in the show notes in case you want to read the article, if I can find it again. I printed it out so I could keep it.

Anyway, the fishermen reported that the sea serpent looked like this:

“The head rose about eight feet out of the water, and resembled a huge turtle’s head…the colour was greyish-green. The eye…was small in comparison to the rest of the monster. The other part in view was three curved humps about 20 feet apart, and each one rose from six feet in the front to a little less in the rear. They were covered with huge scales about the size of saucers, and also covered in barnacles. We could not get a glimpse of the tail, as it was under the water.”

Robert France suggests that this was a sea turtle entangled with a string of fishing gear, specifically fishing floats. He also gives a number of other examples dating back hundreds of years. Fortunately for sea turtles and other animals in the olden days, most fishing nets were made from rope, usually hemp and sometimes cotton, which eventually rotted and freed the animal, if it survived being entangled for months on end.

So if you live around the ocean, or any kind of water for that matter, make sure to pick up any litter you find, especially plastic bags. You could save a lot of lives. Who knows, maybe the sea turtle you save from eating that one fatal plastic bag will grow up to become the biggest sea turtle alive.

As a companion piece to this episode, Patreon subscribers got an episode about the Soay Island Sea Monster sighted in 1959, which was probably a sea turtle of some kind. Just saying.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast online at strangeanimalspodcast.com. We’re on Twitter at strangebeasties and have a facebook page at facebook.com/strangeanimalspodcast. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. If you like the podcast and want to help us out, leave us a rating and review on Apple Podcasts or whatever platform you listen on. We also have a Patreon if you’d like to support us that way.

Thanks for listening!