Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 11:23 — 12.6MB)

Thanks to Mary, Mila, and Riley for their suggestions this week!

Further reading:

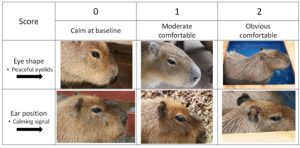

Comfort of capybaras determined by SCIENCE:

An especially attractive guinea pig:

Guinea pigs come in lots of colors, patterns, and fur types [picture taken from this excellent site]:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

This week we’re going to learn about two rodents, one small and one big. Thanks to Mary and Mila who both suggested the guinea pig, and thanks to Riley who suggested the capybara.

This episode is a bit unusual because part of it comes from a Patreon episode from 2023. Like, literally a big chunk of this episode is the original audio from that one, and you’ll be able to tell the difference in audio and know just how lazy I was this week. The episode actually came together in an unusual way too. Riley’s parent emailed me last week with some new suggestions, including capybaras, but wasn’t sure if we had already covered the topic. I thought we had, but of course there’s always more to learn about an animal. Well, since this is the beginning of a new month I was on the Patreon page to upload the December episode, and while I was there I did a quick search for capybaras and discovered the episode I was thinking of. I decided to add some more information about guinea pigs to it since I already mention guinea pigs a lot in that episode, and here is the result!

The capybara is a rodent, and a very big one. It is, in fact, the biggest rodent alive today. To figure out just how big the capybara is, picture a guinea pig. The guinea pig is also a rodent, native to the Andes Mountains in South America. No one’s sure why the guinea pig is called that in English, since it doesn’t come from Guinea and doesn’t have anything to do with anything else called guinea, but as someone who had two pet guinea pigs when I was a kid, I know exactly why they’re called guinea pigs. This is what an actual pig sounds like:

[pig squealing]

And this is what a guinea pig sounds like:

[guinea pig squealing]

Also, it’s sort of shaped like a pig. The guinea pig is a chonky little animal with short legs, only a little stub of a tail, and little round ears. Its face is sort of blocky in shape and it has a big rounded rump, similar to that of a capybara. The guinea pig is actually closely related to the capybara, and is a pretty good-sized rodent in its own right. It grows about 10 inches long, or 25 cm, on average, and roughly half that size tall.

The guinea pig has been domesticated for at least 7000 years, but it wasn’t domesticated for people to keep it as a pet. In South America and many other places now, it’s a very small farm animal raised for its meat. Guinea pig has been an important source of protein for all that time, so important that it was considered sacred in many cultures.

In the early 16th century when Europeans started arriving in South America, sailors took guinea pigs with them on ships so they’d have fresh meat on the voyage. But when the cute little animals arrived in Europe, people started buying them as pets.

Guinea pigs eat plants, mostly grass, and are social animals. If you want a pet guinea pig, make sure to get at least two. Like rabbits and some other animals, including the capybara, the guinea pig excretes special pellets that aren’t poop, but are semi-digested pellets of food. The guinea pig eats the pellets so they can pass through the digestive system again and the body can extract as many nutrients as possible from it. What’s left is then excreted as a regular poop pellet.

Even in places where the guinea pig is routinely kept as livestock and eaten, people breed guinea pigs as pets too. The pet variety is smaller than the meat variety and has different markings and different colors. Guinea pigs naturally have short, smooth hair and are usually reddish-brown in color, but different colors, fur length and texture, and white markings have been bred into different varieties. There are even mostly hairless varieties.

Most people these days are familiar with what a guinea pig looks like, but most people are not familiar with what a capybara looks like.

So, picture a guinea pig. Now, imagine it growing and growing and growing until it’s the size of a large dog. Instead of orange and white, or black and white, or any of the other colors and patterns of a pet guinea pig, imagine its fur as being a solid rusty-brown color. The capybara can grow almost 4.5 feet long, or 134 cm, and can stand up to two feet tall, or 62 cm. That is a big rodent!

The capybara lives throughout most of South America, although it doesn’t live in the Andes or in Patagonia. It’s semi-aquatic and spends a lot of time in the water, sometimes even sleeping in the water with just its nose poking up so it can breathe. It can hold its breath for up to five minutes, and of course it swims extremely well. It even has webbed toes. It eats a lot of water plants and also eats grass, fruit, and other plants and plant parts.

The capybara has some features that are typical of rodents, like its teeth. Rodent teeth grow continuously since they’re easily worn down by chewing, especially chewing tough plants like grass. It also has some features that are uncommon in rodents. For instance, it can’t synthesize vitamin C, a trait it shares with the guinea pig and with humans. If a capybara kept in captivity isn’t given fruit and other foods that contain vitamin C, eventually it will develop scurvy.

But the capybara doesn’t otherwise have any resemblance to a pirate. It’s a sociable animal and famously chill. In the wild it lives in groups that can number up to 100 individuals, although up to 20 is more common.

The capybara has a scent gland on its nose called a morillo. The female has a morillo but the male’s is bigger since he scent marks more often by rubbing the gland on plants, trees, rocks, other capybaras, and so on. During mating season, the female capybara attracts a male by whistling through her nose, because who doesn’t like a lady who can whistle through her nose? The capybara will only mate in water, so if a female decides she doesn’t like a male, she just gets out of the water and walks away from him.

The female usually gives birth to four or five babies in one litter. Females with babies, called pups, help care for the babies of their friends. Most often, the pups who are too young to wander around without someone to watch them carefully, stay in a group. One or two females remain close to the pups to watch them while the other mothers find food, and the babysitters trade out every so often. When a capybara pup gets hungry, if its mother isn’t nearby, another lactating female will allow the pup to drink some of her milk. This is rare in most animals, since producing milk takes a lot of energy and a mother animal naturally wants to expend her energy on her own babies. But it’s beneficial for the whole group for capybara pups to be cared for by all the mothers.

Capybaras are big enough that adults have a certain amount of protection from predators, but they do have to worry about animals like jaguars, caimans, and anacondas. Smaller predators like eagles will eat capybara pups if they can catch them. Fortunately the capybara can swim fast and run fast, and with everyone in its group watching out for danger, it’s a lot safer than it is by itself.

The capybara does well in captivity and is a popular animal in zoos, and in some zoos you might even be able to pet one. You’ve probably seen pictures of capybaras relaxing in what looks like a big outdoor tub with tangerines floating in it, or if you’re from Japan or just familiar with Japanese customs, relaxing in a yuzu bath. Hot springs baths, called onsen, are popular in Japan, and in winter when the days are short and chilly, adding a citrus fruit called yuzu to the bath is supposed to help prevent colds and help moisturize the skin. Some zoos in Japan now extend this custom to capybaras, because it’s adorable.

As an added bonus, it turns out that the yuzu bath is really good for the capybara. The capybara is a warm-weather animal, and winters in Japan can be very cold and dry. As a result, the capybara’s skin becomes dry too. Soaking in natural hot springs, with or without yuzu, restores the capybara’s skin to its normal condition, which is a lot more comfortable for the capybara and helps it stay healthy. We know this is the case because of a study published in December 2021 in the journal Nature.

Before we go, here’s one last interesting fact about the guinea pig, to bring us back to the beginning of this episode. The guinea pig is a fully domesticated animal and its wild ancestor appears to have gone extinct. There are related species that resemble a guinea pig, but there are no wild guinea pigs in the world today.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us for as little as one dollar a month and get monthly bonus episodes.

Thanks for listening!