Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 12:33 — 12.8MB)

Thanks to Lorenzo for suggesting the northern gannet this week! We’ll also learn about an extinct ancestor of the gannet, called plotopterids!

Don’t forget to enter our book giveaway! Details here.

The northern gannet is the assassin of the bird world, probably:

DIVING! It’s what they do:

Northern gannets hanging out on their nesting grounds:

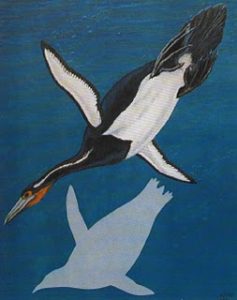

An artist’s rendition of a plotopterid, with the silhouette of a modern emperor penguin for comparison. Picture from March of the Fossil Penguins.

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

This week let’s learn about two interesting birds! Thanks to Lorenzo for the suggestion!

But first, an announcement! I’m doing a giveaway of my books Skytown and Skyway! The giveaway runs through October 31, 2020 and is open to anyone in the world. To enter, just let me know you’d like to enter. You can email me at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com, leave me a message on Twitter or Facebook, or anything else. All I ask is that you make it clear that you want to enter and let me know how to contact you if you win. On Halloween night at midnight I’ll choose one name at random from everyone who enters and that person will win one paperback copy of each book, and I’ll also throw in some stickers, bookmarks, a pencil that says “I bite mean people,” and probably some other stuff. I’ll also sign the books if you like. If you want to take a look at the books to see if they sound interesting, I made a new page on the strangenanimalspodcast.blubrry.net website with links. Please enter. It will be embarrassing if no one does.

Anyway, Lorenzo wants to hear about the northern gannet, a sea bird that sort of looks like a gull who mastered the blade and is probably an assassin. Its bill is large, silvery-blue, and dagger-like, outlined with black at the base that makes a dramatic mask. This mask is actually bare of feathers, showing the bird’s black skin. Otherwise it’s mostly white, with a wash of pale golden on the head and neck, black-tipped wings, and gray legs with webbed toes. But it’s also really big, almost the size of a pelican. Its wingspan can be over six feet, or 184 cm. It can weigh almost 8 lbs, or 3.6 kg, too.

Like many sea birds, the northern gannet breeds in colonies that can number in the thousands, and it only breeds on oceanside cliffs, mostly on islands off the coast of eastern Canada, Iceland, and western Europe. It’s especially common around the British Isles. So many birds may be nesting at once that the cliffs appear white from a distance, like snow fell on the clifftops, but instead of snowflakes, it’s gannets!

While the northern gannet will sit on the water after diving, the only time it actually sets foot on land is when it breeds. It doesn’t walk very well, which is why it nests on cliffs. It’s easier for it to get airborne from a cliff. It can only take off from the water by facing into the wind and flapping hard, but if it’s not windy enough it can’t get airborne and it just has to float there until the wind picks up, probably feeling pretty foolish. But it swims well so if it is stuck on the water, it can swim along with its head under water, looking for fish it can grab.

But most of the time the northern gannet is in the air, and it is built for speed and efficiency. Its long, narrow wings allow it to reach high speeds, up to 40 mph, or 65 km/h. It’s not very maneuverable, though, except for one specific move. The northern gannet is a diver. It’s a diver extraordinaire! It can reach incredible speeds while diving, up to 62 mph, or 100 km/h. When it dives, it holds its body rigid and angles its wings back, then folds the wings tight against its body just before it hits the water. It can dive up to 36 feet deep, or 11 m, and then it will swim farther down, sometimes over 80 feet deep, or 25 m. Its eyes are sharp and adapted to seeing both underwater and above water, so that as soon as it plunges into the water it can look around for fish. It uses both its feet and its wings to maneuver underwater.

The northern gannet mostly eats fish, but it will also eat squid if it happens to come across one. It prefers small fish like sardines and anchovies, but any fish that swims in a shoal is its favorite. Groups of northern gannets will dive together into a shoal of fish, and swallow the fish underwater. The northern gannet especially likes to follow whales and fishing boats to grab fish trying to escape, injured fish, or fish that are discarded as too small or the wrong kind.

Northern gannets live a long time, with the oldest known bird living past 34 years old. It’s not considered an adult until it’s about five years old. Breeding season starts in spring. The male finds a nesting site, or reclaims the nesting site he used the previous year, and defends it from other males, while females fly over the island and look for a male with a nesting site they like. Pairs generally mate for life, so many females are looking for their mates from the previous year. When a female has found a mate, she lands and displays her wings, while the male displays his neck and shakes it in a little courtship dance.

The male collects seaweed, grass and other plants, feathers, even dirt to build the nest. He’ll basically bring back anything he can find to add to the nest, and researchers have found some weird stuff in gannet nest walls. This includes golf balls, a set of false teeth, a gold watch, and a plastic frog. Not all in the same nest, though. Nests are always just a few feet apart, or maybe 60 cm, even though gannets are fiercely territorial and will fight any other gannet that comes into its little territory.

The female lays one egg. Both the male and female take turns keeping the egg warm, which they do by wrapping their big webbed feet around it. Usually their feet are cool, but during nesting season their feet stay much warmer. The parents will keep the baby warm the same way, wrapping their feet around it. One parent will stay with the chick while the other flies out to fish.

When northern gannet chicks are ready to learn how to fly, they don’t get a chance to practice. I mean, they nest on cliffs. You get one try and you better be lucky or splat. And once they’re flying, they’re on their own and don’t return to the nest. They stay at sea for the next few years, then return to the nesting ground where they hang out in groups near the edges. Even though they don’t breed for a few more years after that, hanging out in the colony helps them learn where the best fishing spots are in the area.

I can’t count how many times I’ve had to say that an animal is threatened by habitat loss, hunting, and so on, but I’m happy to report that the northern gannet is not threatened by anything. It’s doing just fine, and in fact its numbers are increasing after it stopped being hunted extensively in the early 20th century. Its main problem in life is probably a bird called the skua, another sea bird that’s mostly black, brown, and gray. The skua is much smaller than the northern gannet but it’s aggressive, and will kill and eat smaller birds. The northern gannet is much too big to kill, so instead the skua will fly up to a gannet and grab its wing. The gannet falls to the water, where the skua will either keep hold of its wing so it can’t take off again, or will just peck it. Either way, it won’t leave the gannet alone until it regurgitates whatever fish it’s eaten recently but hasn’t digested, which the skua eats.

This is what the northern gannet sounds like:

[northern gannet sounds]

While I was researching the northern gannet, I ran across an article about extinct relations called plotopterids. Plotopterids probably looked a lot like penguins. They also probably acted like penguins, using their short wings as flippers while swimming to catch fish. But they weren’t penguins. They weren’t even related to penguins, or even to the similar-looking great auk, which we talked about in episode 78. They were related to gannets, cormorants, and boobies, which are all sea birds that can fly.

Plotopterids lived in the northern hemisphere between around 35 and 25 million years ago, with fossils of the birds discovered in various places around northwestern North America and Japan. But they were huge! They were even bigger than the extinct giant penguins of the southern hemisphere that could grow almost five and a half feet long, or 1.6 meters. The biggest species of plotopterid known could grow six and a half feet long, or 2 meters.

The similarities between penguins and plotopterids are due to convergent evolution, where animals that share similar environmental conditions develop similar traits. We don’t know whether plotopterids had the same black and white coloring that penguins have, but it’s a good bet that they did. Most sea birds are black and white. Even most diving ducks that live in fresh water are black and white, whereas dabbling ducks have more varied colors. The most obvious difference between penguins and plotopterids, though, is the neck. Penguins have relatively short necks. Plotopterid necks were longer.

Researchers are studying plotopterids to learn why these birds and penguins evolved to swim using their wings. Most birds that can swim use their feet to propel them along in the water. One scientist in the study I read about, Dr. Gerald Mayr, says, “We think both penguins and plotopterids had flying ancestors that would plunge from the air into the water in search of food. Over time these ancestor species got better at swimming and worse at flying.”

I bet the young northern gannets who are about to try flying for the first time wish they were a little more like plotopterids and could just swim away from the nest.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast online at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, suggestions for future episodes, or want to enter the book giveaway, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. If you like the podcast and want to help us out, leave us a rating and review on Apple Podcasts or just tell a friend. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us that way.

Thanks for listening!