Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 21:21 — 21.8MB)

This week’s episode is about some invertebrates who look like they’re made of velvet! Thanks to Rosy and Simon for their suggestions!

Further reading:

Structure and pigment make the eyed elater’s eyespots black

The red velvet mite looks like a tiny red velvet cake but is NOT CAKE, NOT A SPIDER, NOT A SPIDER CAKE:

GIANT RED VELVET MITE:

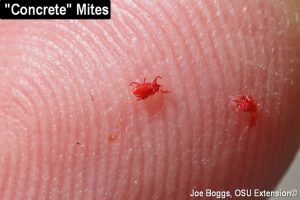

Regular sized red velvet mites on a fingertip and one parasitizing a daddy long legs spider:

An eastern velvet ant female (it’s actually a wasp, not an ant):

Velvet worms on hands:

A blue velvet worm!

Look at its teeny mouf!

An eyed click beetle DO YOU SEE THE EYES(pots):

The velvet asity (maybe you notice that it’s uh not an invertebrate):

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

As we continue invertebrate August, we’ve got a nicely themed episode this week, velvet invertebrates! Thanks to Simon and Rosy for their suggestions!

First, let’s talk about Rosy’s suggestion, the red velvet mite. It sounds delicious, but only because it makes me think of red velvet cake. But the red velvet mite is an arachnid, related to spiders and scorpions–but it’s not actually a spider.

In English, the word mite, spelled m-i-t-e, means a tiny thing, and mites are tiny. Most are under a millimeter long. Scientists actually group mites into two kinds, parasitic mites that are closely related to ticks, and velvet mites that are closely related to chiggers. Chiggers, my least favorite. All the many species of velvet mite and chigger are in the order Trombidiformes.

You know what? Let’s talk briefly about chiggers, because there’s a lot of bad information about them out there. The chigger lives in vegetation, especially tall weeds and shrubs. Various species live throughout the world but it’s more common in warm, humid areas. In some places it’s called a harvest mite or scrub-itch mite.

The chigger is only parasitic as a larva. The larvae only have six legs, compared to adults that have eight. A larva waits on a blade of grass or a leaf for an animal to brush past it, and when it does, the larva grabs on. The longer you stay in one place, for instance when you’re blackberry picking, the more likely it is that a chigger will crawl onto you. It’s very nearly microscopic so you can’t look for chiggers and pick them off the way you can ticks. Like velvet mites, they’re red in color but generally paler than actual velvet mites.

A chigger bite causes intense itching, swelling, redness, and takes sometimes several weeks to heal, especially if you scratch it. It also gets infected easily. Many people believe that the chigger actually burrows into the skin. The chigger does eat skin cells from the layers of skin below the outer layer, but they don’t actually have mouthparts that can bite that deeply. They certainly can’t burrow into the skin. What they do instead is give the skin a little bite and inject digestive enzymes into the wound. The enzymes break down the skin cells they touch, and also harden the tissues around the wound. The chigger slurps up the liquefied skin cells and injects more enzymes, which seep down deeper into the skin, until basically what it’s created is a tube of hardened skin cells that reaches the lower layers of skin. The tube is called a stylosome, in case you were wondering. All this takes several days, so the best way to treat chigger bites before they get bad is to take a hot shower as soon as possible after you’ve been blackberry picking or whatever, and scrub well, especially around places where your clothing was tight. You also need to wash your clothes in hot, soapy water to kill any chiggers still on them.

The best way to deal with chiggers is to wear a good insect repellent and make sure to apply it all the way from your feet up, paying special attention to ankles, the backs of your knees, and around your waist and stomach.

Okay, that’s enough of that. Let’s talk about actual red velvet mites that don’t bite and that you can see. The red velvet mite is covered with short, dense hairlike structures that may act as sensors to help the mite find its way around in the dark or underground. The hairs are orangey-red, although some species may have white spots. Adults have eight legs like spiders do, but each pair of legs grows from a different part of the cephalothorax instead of from the same place like in spiders. Adult red velvet mites generally eat insect larvae and eggs. But the red velvet mite larvae are parasites—but not chigger-type parasites. They don’t bother people or pets, and in fact they only parasitize invertebrates like insects and spiders. A red velvet mite larva will grab onto certain types of insect like grasshoppers or beetles, or some spiders like daddy long-legs. It rides around on the insect and sucks its hemolymph like eensy-beensy insect ticks.

To attract a female, the male red velvet mite leaves droplets of sperm on twigs and grass in a little area and spins an intricate trail of silk leading to the droplets. The female examines the silk trail and if she finds it well-made, she’ll gather up some of the sperm to fertilize her eggs. But if another male comes across the trail, he’ll tear it up. The female lays her eggs in the soil.

There are thousands of species of velvet mite throughout the world, with many more undoubtedly yet to be discovered. Most are teensy, but there are some bigger species called giant red velvet mites.

There are actually two totally different mites called by that name. The first one lives in southwestern North America in dry areas, and includes several species in the genus Dinothrombium. The adults eat ants and termites. Like other mites, people are most likely to see them walking around on outside walls or patios or deck railings, usually lots of them in one area and often after summer rain. That’s why they’re sometimes called rain bugs. But while most velvet mites are just little moving red dots, the giant red velvet mite can grow up to 12 mm, which is almost half an inch long. In the mite world, that really is giant.

The other species called the giant red velvet mite lives in parts of northern India in dry areas, Trombidium grandissumum, and it can grow up to two cm long, or over ¾ of an inch. Like most other red velvet mites, it mostly lives underground and eats insect larvae, many of which are harmful to crops.

So why are red velvet mites so red? Surely that would make them easier for predators to see. Well, the red velvet mite contains compounds that make them taste bad and may be toxic, so the bright red color advertises that to predators.

The red velvet mite will curl its legs in to make itself smaller if it feels threatened, which is oddly sweet. Be safe, little mites.

Next, let’s learn about the velvet ant. It’s not an ant at all but a wasp, although wasps and ants are closely related. The female has no wings although the male does, but the male doesn’t have a stinger while the female does. Sometimes it’s called the cow killer ant because its sting is so painful that people think it could practically kill a cow. It can’t kill a cow. Or a person, for that matter, but one species of velvet ant was scored for how painful its sting was and it ranks right up there with bullet ants.

Like the red velvet mite, there are thousands of species of velvet ant that live throughout the world. The females and usually the males have plush-looking hairs, some species with orange or red hairs, some with other colors and patterns like black and white. In the case of the velvet ant, the bright coloration is to warn potential predators that this is a dangerous wasp and they should steer clear! It’s also a tough insect with a thick exoskeleton.

The biggest species of velvet ant is the eastern velvet ant, which lives in the eastern United States. It can grow almost two centimeters long, or three-quarters of an inch, and is orangey-red with a black stripe on its abdomen and black legs.

If you remember way back to episode 28, about crawdads and cicadas, we talked briefly about a huge wasp called the cicada killer. The cicada killer can grow up to two inches long, or 5 cm, which is simply enormous when one gets into your house and you worry it’s going to just move in and complain that the furniture is too small. Anyway, the cicada killer does something horrible to the cicada. The female stings a cicada, which paralyzes it but doesn’t kill it. Then it carries the cicada to its burrow and lays an egg on it. When the egg hatches a day or two later, the larva eats the still-living cicada.

Well, I bring this up because velvet ants do the same thing to cicada killers! Comeuppance in the insect world! The female velvet ant searches for cicada killer burrows, and when it finds one with a larva inside, eating a cicada, it lays an egg on the larva. The egg hatches and the velvet ant larva promptly eats the cicada killer larva which is in turn eating the cicada. This is a way different circle of life than they talked about in the Lion King.

Next, let’s talk about a different kind of invertebrate, the velvet worm. It’s not a worm and it’s also not fuzzy like the animals we’ve talked about so far, but its body does have a soft, velvety texture. There are about 180 species known in two families. It lives in tropical areas in Central and South America, the Caribbean, parts of Africa and Asia, and Australia and New Zealand, but we know it used to be more widespread because we’ve found velvet worms in Baltic amber from what is now northern Europe. It has a soft, segmented body that’s covered with a very thin layer of chitin with tiny overlapping scales. This makes the velvet worm look velvety and acts as a water repellent so the body won’t dry out, but it also needs plenty of humidity in its environment to survive.

At first glance, the velvet worm looks like a caterpillar. It has a caterpillar’s stumpy bumps of legs and a long soft-looking body like a caterpillar. Various species grow to various sizes, but the largest is only about eight inches long, or 20 cm, and most are much shorter. Different species are different colors, from brown or reddish to blue, white, or even bright green like a caterpillar. But it’s not related to any animal that goes through a caterpillar-like stage of life. Scientists aren’t even completely sure what the velvet worm is actually most closely related to. It shares features with some of the strange animals that evolved during the Cambrian, and currently many researchers think it’s a descendant of a group of Cambrian animals called lobopodians, a group which includes Hallucigenia. You may remember Hallucigenia from episode 69.

Some beautifully preserved fossil ancestors of velvet worms have been found in a Canadian fossil bed dated to 425 million years ago. While modern velvet worms live exclusively on land, its 425 million years old ancestors lived in shallow coastal water.

These days, velvet worms are uncommon animals that mostly live in leaf litter or under rotting logs or similar places. Two species even live in caves. It’s mostly nocturnal, although it will come out during the day in rainy weather. During the day, or when it’s too dry or cold for its liking, it will rest in tiny crevices in its habitat. That may be just a deep crack in the earth or a rock, a tunnel originally dug by termites, or a little hidden spot inside a rotting log. It’s eaten by a lot of animals, including birds, insects, spiders, rodents, and snakes, so it’s good at hiding.

But when the velvet worm is out hunting, it is fearsome to its prey. It mostly eats small invertebrates like insects, worms, spiders, and snails, but it can kill animals its own size or even a little larger. And it doesn’t need to eat very often, maybe once a week or even just once a month.

The velvet worm has a pair of retractable antennae that act as feelers that the velvet worm uses to very lightly touch potential prey to see whether it wants to attack. It will sneak up on an animal and use these feelers to touch it so lightly that the animal has no idea the velvet worm is there or is touching it. If that doesn’t creep you out completely, you haven’t read the spooky horror stories I’ve read, that’s all I can say. At the base of the antennae the velvet worm has a pair of eyes, although some species don’t have eyes at all.

The velvet worm’s mouth contains a sharp pair of mandibles, but these are actually inside the mouth, sort of like teeth although they’re nothing like teeth, rather than external mandibles like those of insects. But it’s behind the mouth where things get really interesting, because that’s where the slime is secreted. The velvet worm has a pair of slime glands in its body that generate and hold extremely sticky slime. The velvet worm squirts it from two tiny openings on the sides of its head to form a sort of net that ensnares its prey. If the prey is large or strong, the velvet worm may squirt more slime at its legs to keep it immobilized.

The slime immediately starts to dry and harden, and as it dries it contracts. Then the velvet worm bites the animal and injects digestive saliva into the wound that liquefies the tissues it comes in contact with. Sort of like a chigger. While it’s waiting for the saliva to do its work, the velvet worm eats up the slime it discharged, because it’s made of proteins and takes several weeks to regenerate. Then the velvet worm clamps its mouth over the wound and slurps up the liquefied insides of its prey, which by the way is very dead by this point.

But the really amazing thing is that some species of velvet worm are social. It lives in family groups that hunt together, led by a dominant female. She eats first, then the other females, then the males, then any young. Females are usually larger than males.

Velvet worms have been well studied and I could go on and on about them. I might return to them eventually and give them their own episode. But let’s go on now to our last velvet animal, the velvet asity.

Simon suggested the velvet asity of Madagascar when we were talking on twitter about an insect called the eyed elater, or eyed click beetle, which lives in forests in North and Central America. It’s a slender beetle that grows about 2.5 inches long, or 4.5 cm. The larvae are sometimes called wireworms because they’re so long and skinny. They eat the grubs of other beetles that live in rotting wood, but it’s not known what the adults eat, if anything.

Like other click beetles, if it feels threatened, the eyed click beetle can suddenly launch itself away with its click mechanism. This is a spine underneath its thorax that fits into a groove between its legs. If the insect is threatened, it flexes its body to release the spine, which snaps against whatever surface the beetle is touching and catapults it sometimes several inches away.

The eyed click beetle is black and mottled gray to blend in with tree bark, but it has two large eye spots that are probably meant to frighten predators away. The eye spots are black outlined with white, and the black part contains cone-shaped microtubules made of modified setae that contain the pigment melanin. Between the pigment and the shape of the hairs and the way they’re aligned, the eyespots absorb 96.1% of light that hits them. This makes them look much larger and more conspicuous to potential predators.

Quite a few insects and some other animals have developed similar coloring that will absorb light, often called super-black. And that brings us to the velvet asity, the male of which is almost all super-black as an adult except for bright lime green wattles above the eyes.

Uh, and this is where I have to admit I made a mistake. I often take quick notes about animals people recommend, especially if the recommendation comes from a Twitter conversation that’s easily lost. Later on I transfer my notes to the big ideas spreadsheet. Well, this time I made a note that said “Velvet asity of Madagascar, Simon replied with this to a twitter post about the eyed elater, with specialized hairs in the eyespots that deaden reflection.” That’s literally what’s in my notes, and I listed it under the invertebrates tab because I forgot what the velvet asity is and just assumed it was another insect like the eyed click beetle.

But the velvet asity isn’t an invertebrate, which I only discovered after I’d started researching the other velvet animals in this episode. It’s a bird. But what a bird it is! It’s a little round bird with a very short tail, short wings, and amazing coloration! While the female is a streaky olive color, the male’s breeding plumage is striking.

The super-black coloring of the male velvet asity deadens reflections and makes its green eyebrows look even brighter, which attracts females. The velvet asity lives in the rainforests of Madagascar and mostly eats fruit, but it will also eat nectar and some insects. During breeding season, males gather in small groups called leks to show off for females with a mating dance that involves him flipping all the way around the branch he’s standing on. The female weaves a pear-shaped nest that hangs from a branch and is camouflaged because she uses materials like strips of bark, leaves, and moss to make it. She also takes care of the eggs and chicks by herself. All the male does is show off, but you can hardly blame him. If you’ve got it, flaunt it, velvet asity.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast online at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. If you like the podcast and want to help us out, leave a rating and review on Apple Podcasts or just tell a friend. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us that way.

Thanks for listening!