Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 16:44 — 18.9MB)

It’s the annual discoveries episode! Thanks to Stephen and Aryeh for their corrections and suggestions this week!

Further reading:

Salinella Salve: The Vanishing Creature That Defied Science for Over a Century

Three new species of the genus Scutiger

A new species of supergiant Bathynomus

Giant ‘Darth Vader’ sea bug discovered off the coast of Vietnam

A New Species of easter egg weevil

Bizarre ‘bone collector’ caterpillar discovered by UH scientists

1,500th Bat Species Discovered in Africa’s Equatorial Guinea

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

This week we’re going to learn about some animals discovered in 2025! We’ll also make this our corrections episode. This is the last new episode we’ll have until the end of August when we reach our 500th episode, but don’t worry, until then there will be rescheduled Patreon episodes every single week as usual.

We’ll start with some corrections. Shortly after episode 452 was published in September, where we talked about the swamp wallaby and some other animals, Stephen emailed to point out that I’d made a major mistake! In that episode I said that not all animals called wallabies were actually members of the family Macropodidae, but that’s actually not the case. All wallabies are macropodids, but they aren’t all members of the same genus in that family. I corrected the episode but I wanted to mention it here too so no one is confused.

Stephen also caught another mistake in episode 458, which is embarrassing. I mentioned that marsupials didn’t just live in Australia, they were found all over the world. That’s not actually the case! Marsupials are found in North and South America, Australia, New Guinea and nearby areas, and that’s it. They were once also found in what is now Asia, but that was millions of years ago. So I apologize to everyone in Africa, Asia, and Europe who were excited about finding out what their local marsupials are. You don’t have any, sorry.

One update that Aryeh asked about specifically is an animal we talked about in episode 445, salinella. Aryeh emailed asking for more information if I could find any, because it’s such a fascinating mystery! I looked for some more recent findings, unfortunately without luck. I do have an article linked in the show notes that goes into detail about everything we covered in that episode, though, dated to mid-January 2026, and it’s a nice clear account.

Now, let’s get into the 2025 discoveries! There are lots more animals that were discovered last year, but I just chose some that I thought were especially interesting. Mostly I chose ones that I thought had funny names.

Let’s start with three new species of frog in the genus Scutiger. Species in this genus are called lazy toads and I couldn’t find out why. Maybe they don’t like to move around too much. Lazy toads live in mountains in some parts of Asia, and we don’t know very much about most of the 31 species described so far. Probably the most common lazy toad is the Sikkim lazy toad that lives along high altitude streams in the Himalaya Mountains. It’s mottled greenish-brown and yellowish in color with lots of warts, and while its feet have webbed toes, it doesn’t have webbed fingers on its little froggy hands. This is your reminder that every toad is a frog but not every frog is a toad. The Sikkim lazy toad grows about two and a half inches long, or about 65 mm, from nose to butt. It seems to be pretty average for a lazy toad.

The three new species of lazy toad are found in Yunnan Province in China, in a mountainous region where several species of lazy toad were already known. Between 2021 and 2024, a team of scientists collected 27 lazy toads from various places, then carefully examined them to see if they were species already known to science. This included genetic analysis. The team compared their findings with other lazy toad species and discovered that not all of the specimens matched any known species. Further comparison with each other revealed that the team had discovered three new species, which they described in December of 2025.

Next, isopods are common crustaceans that live throughout the world. You have undoubtedly seen at least one species of isopod, because an animal with lots of common names, including woodlouse, pill bug, roly-poly, and sowbug, is a terrestrial isopod. That’s right, the roly-poly is not a bug or a centipede but a crustacean. The order Isopoda contains more than 10,000 species, and there are undoubtedly thousands more that haven’t been discovered by scientists yet. About half the species discovered so far live on land and the other half live in water, most in the ocean but some in fresh water. They don’t all look like roly-polies, of course. Many look like their distant crustacean cousins, shrimps and crayfish, while others look more like weird centipedes or fleas or worms. There’s a lot of variation in an animal that’s extremely common throughout the world, so it’s no surprise that more species are discovered almost every year.

In 2021 and 2022, a team of Spanish scientists took a biological survey of an ancient Roman tunnel system beneath Carmona, Spain. The tunnels were built around 2,000 years ago as a water source, since they capture groundwater, but it hasn’t been used in so long that it’s more or less a natural environment these days.

The scientists quickly discovered plenty of life in the tunnels, including an isopod living in cracks in some ancient timbers. It grows about two and a half millimeters long and actually does look a lot like a tiny roly-poly. It has long antennae and its body mostly lacks pigment, but it does have dark eyes. Most animals that live in total darkness eventually evolve to no longer have functioning eyes, since they don’t need them, but that isn’t the case for this new isopod. Scientists think it might take advantage of small amounts of light available near the tunnel entrances.

As far as the scientists can tell, the Carmona isopod only lives in this one tunnel system, so it’s vulnerable to pollutants and human activity that might disrupt its underground home.

Another new isopod species that’s vulnerable to human activity, in this case overfishing, lives off the coast of Vietnam. It’s another isopod that looks a lot like a roly-poly, which I swear is not what every isopod looks like. It’s a deep-sea animal that hunts for food on the ocean floor, and it’s a popular delicacy in Vietnam. Remember, it’s a crustacean, and people say it tastes like another crustacean, lobster. In fact, scientists discovered their specimens in a fish market.

Deep-sea animals sometimes feature what’s called deep-sea gigantism. Most isopods are quite small, no more than a few cm at most, but the new species grows almost 13 inches long, or over 32 cm. It’s almost the largest isopod known. Its head covering made the scientists think of Darth Vader’s helmet, so it’s been named Bathynomus vaderi.

Next we have a new species of Easter egg weevil, a flightless beetle found on many islands in Southeast Asia. Easter egg weevils are beautiful, with every species having a different pattern of spots and stripes. Many are brightly colored and iridescent. The new species shows a lot of variability, but it’s basically a black beetle with a diamond-shaped pattern that can be yellow, gold, or blue. Some individuals have pink spots in the middle of some of the diamonds. It’s really pretty and that is just about all I could find out about it.

Another new insect is a type of Hawaiian fancy case caterpillar, which metamorphose into moths. They’re only found on the Hawaiian islands, and there are over 350 species known. The new species has been named the bone collector, because of what the caterpillar does.

Fancy case caterpillars spin a sort of shell out of silk, which is called a case, and the caterpillar carries its case around with it as protection. Some of the cases are unadorned but resemble tree bark, while many species will decorate the case with lichens, sand, or other items that help it blend in with its background. Some fancy case caterpillars can live in water as well as on land, and while most caterpillars eat plant material, some fancy case caterpillars eat insects.

That’s the situation with the bone collector caterpillar. It lives in spider webs, which right there is astonishing, and decorates its case with bits and pieces of dead insect it finds in the web. This can include wings, heads, legs, and other body parts.

The bone collector caterpillar eats insects, and it will chew through strands of the spider’s web to get to a trapped insect before the spider does. Sometimes it will eat what’s left of a spider’s meal once the spider is finished.

The bone collector caterpillar has only been found in one tiny part of O’ahu, a 15-square-km area of forest, although researchers think it was probably much more widespread before invasive plants and animals were introduced to the island.

Next, the Antarctic Ocean is one of the least explored parts of the world, and a whole batch of new species was announced in 2025 after two recent expeditions. One of the expeditions explored ocean that was newly revealed after a huge iceberg split off the ice shelf off West Antarctica in early 2025. That’s not where the expedition had planned to go, but it happened to be nearby when the iceberg broke off, and of course the team immediately went to take a look.

Back in episode 199 we talked about some carnivorous sponges. Sponges have been around for more than half a billion years, and early on they evolved a simple but effective body plan that they mostly still retain. Most sponges have a skeleton made of calcium carbonate that forms a sort of dense net that’s covered with soft body tissues. The sponge has lots of open pores in the outside of its body, which generally just resembles a sack or sometimes a tube, with one end attached to something hard like a rock, or just the bottom of the ocean. Water flows into the sponge’s tissues through the pores, and special cells filter out particles of food from the water, much of it microscopic, and release any waste material. The sponge doesn’t have a stomach or any kind of digestive tract. The cells process the food individually and pass on any extra nutrients to adjoining cells.

In 1995, scientists discovered a tiny sponge that wasn’t a regular filter feeder. It had little hooks all over it, and it turns out that when a small animal gets caught on the hooks, the sponge grows a membrane that envelops the animal within a few hours. The cells of the membrane contain bacteria that help digest the animal so the cells can absorb the nutrients.

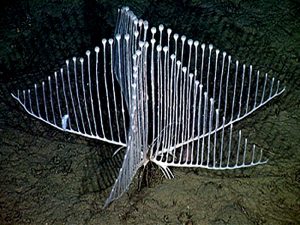

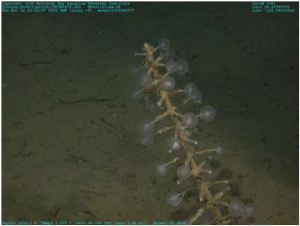

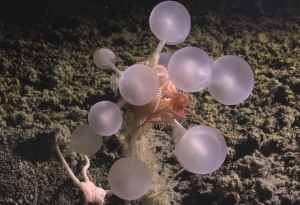

Since then, other carnivorous sponges have been discovered, or scientists have found that some sponges already known to science are actually carnivorous. That’s the case with the ping-pong tree sponge. It looks kind of like a bunch of grapes on a central stem that grows up from the bottom of the ocean, and it can be more than 20 inches tall, or 50 cm. The little balls are actually balloon-like structures that inflate with water and are covered with little hooks. It was discovered off the coast of South America near Easter Island, in deep water where the sea floor is mostly made of hardened lava. It was classified in the genus Chondrocladia, and so far there are more than 30 other species known.

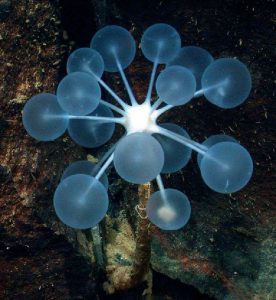

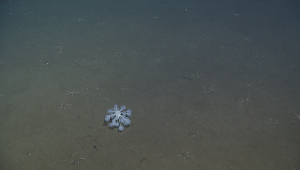

The reason we’re talking about the ping-pong tree sponge is that a new species of Chondrocladia has been discovered in the Antarctic Ocean, and it looks a lot like the ping-pong tree sponge. It’s been dubbed the death-ball sponge, which is hilarious. It was found two and a quarter miles deep on the ocean floor, or 3.6 km, and while scientists have determined it’s a new species of sponge, it hasn’t been described yet. It’s one of 30 new species found so far, and the team says that there are many other specimens collected that haven’t been studied yet.

We haven’t talked about any new mammal discoveries yet, so let’s finish with one of my favorites, a new bat! It was discovered on Bioko Island in Equatorial Guinea, which is part of Africa. During a 2024 biodiversity assessment on the island, a PhD student named Laura Torrent captured a bat that turned out to be not only a brand new species, it is the 1,500th species of bat known to science!

Pipistrellus etula gets its name from the local language, Bantu, since “etula” means both “island” and “god of the island” in that language. The bat was found in forests at elevations over 1,000 meters, on the slopes of a volcano. Back in 1989, a different researcher captured a few of the bats on another volcano, but never got a chance to examine them to determine if they were a new species. When Torrent’s team were studying their bats, one of the things they did was compare them to the preserved specimens from 1989, and they discovered the bats were indeed a match.

P. etula is a type of vesper bat, which is mostly active at dusk and eats insects. It’s brown with black wings and ears. Just like all the other species we’ve talked about today, now that we know it exists, it can be protected and studied in the wild.

That’s what science is really for, after all. It’s not just to satisfy our human curiosity and desire for knowledge, although that’s important too. It’s so we can make this world a better place for everyone to live—humans, animals, plants, isopods, weird caterpillars, and everything else on Earth and beyond.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. Thanks for listening! I’ll see you in August.