Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 12:56 — 14.9MB)

Sign up for our mailing list! Even though I hardly ever send an email to it!

It’s INVERTEBRATE AUGUST! Thanks to Elizabeth, Richard, and Llewelly for their suggestions this week!

Further reading:

Meet Phylliroe: the sea slug that looks and swims like a fish

Hey, so these sea slugs decapitate themselves and grow new bodies

Found, Then Lost, Then Found Again: Scientists Have Rediscovered the Sand Octopus

A sand crab in the air:

Sand crabs in the water, feeding:

Phylliroe is a sea slug that looks like a fish (pictures from article linked to above):

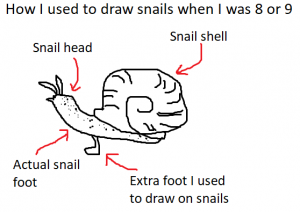

How I used to draw snails when I was a kid, adding an extra foot because I didn’t understand that the “foot” of a snail/slug is the flat part of the body that touches the ground:

The mysterious sand octopus in mid-swim:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

It’s the first week of invertebrate August and we’re heading to the ocean for our first episode! Let’s jump right in with an episode about sand crabs, a couple of sea slugs, and an octopus mystery that was recently solved. Thanks to Elizabeth, my brother Richard, and Llewelly for their suggestions!

We’ll start with Elizabeth’s suggestion. The sand crab is also called the sand bug, the mole crab, or similar names that refer to its habit of burrowing into the sand. It’s common throughout much of the world’s oceans, especially in warm areas, and can be extremely numerous. It’s also sometimes called the sand flea, but it’s not the kind of tiny jumping crustacean that bites, also called the sand flea. This little crustacean is harmless to humans. It doesn’t even have pincers.

The sand crab isn’t a true crab although it is closely related to them. It’s gray-brown and has a tough carapace to protect it when it’s washed around by waves and to help protect it from predators. Females are larger than males and can grow up to an inch and a half long in the largest species, or about 35 mm, and an inch wide, or 25 mm. So it’s longer than it is wide, unlike most crabs, and its carapace is domed sort of like a tiny tortoise shell. Overall, it’s shaped sort of like a streamlined barrel. I saw one site that called it the sand cicada and it is actually about the same size and shape as a cicada, which it isn’t related to at all except that they’re both invertebrates. Some species have little spines on the carapace while others are smooth.

The sand crab lives in the ocean, specifically in the intertidal zone right at the area where waves wash up on the beach. This is called the swash, by the way, which is a great word. The sand crab burrows into the sand tail-first, using its strong rear legs, and during the time that there’s water over the sand, it unfurls its feathery antennae to filter tiny food particles from the water. When the wave goes out, it retracts its antennae and works on staying buried in the sand as the next wave rolls in.

In some species, males are very similar to females, but smaller. In other species, they’re tiny, barely 3 mm long at most, and even as adults they resemble larvae. The male finds a female and grabs hold of her leg, and there he stays. I tried to find out more about this, but it doesn’t look like the humble sand crab gets a lot of attention. If you’re interested in becoming a scientist who studies invertebrates and you want to spend a lot of time on the beach, the sand crab would make a good study buddy.

Lots of fish and birds eat sand crabs, and people do too. In many places they’re considered a delicacy and grilled as a snack. This isn’t surprising since they’re related to other crustaceans people like to eat, like crabs and lobsters.

Next, let’s learn about two strange sea slugs. We’ve talked about sea slugs a few times before, including in episodes 215 and 129, but there are a lot of species, with more being discovered pretty often.

Llewelly sent me a link ages ago about a sea slug that’s related to the sea bunny, which we talked about in the cutest invertebrates episode, 215. It’s called Phylliroe and doesn’t look like a little bunny or a slug. It looks like a fish.

Phylliroe grows a few inches long at most, or 5 cm, and the article Llewelly sent, which I’ve linked to in the show notes, points out that it’s about the size of a goldfish. Its rear end is shaped roughly like a fish tail, which it uses just like a fish tail to propel itself through the water. It’s probable that Phylliroe’s shape doesn’t have anything to do with disguising it, but instead is just the result of convergent evolution. A body streamlined to move through the water with minimal resistance is always going to be fish-shaped, because that’s why fish are shaped the way they are. The fish-like tail is also an efficient way to move through the water relatively quickly.

Phylliroe mostly eats tiny jellyfish, which it grabs with its small foot. It doesn’t need a big flat foot to glide on, since it doesn’t live on the sea floor like some of its relations, so over many, many generations its foot has become smaller and smaller until it’s just a little tiny foot near its mouth. It’s still sticky, though, which means jellies stick to it, which means it’s easier for Phylliroe to eat the jellies.

Phylliroe is mostly see-through, although you can see its digestive system. It also has two so-called horns, called rhinophores, that it probably uses to sense the chemical signature of its prey in the water. If you remember the sea bunny, its rhinophores look like bunny ears. Phylliroe’s look more like thick antennae or barbels. Phylliroe also exhibits bioluminescence, which is not a typical trait for a sea slug.

My brother Richard alerted me to another sea slug a while back, this one referred to as the Deadpool slug. The reason why it’s called the Deadpool slug is lost on me because I haven’t seen that movie or read the comic book, but the sea slug can separate its head from its body when it wants to, and it just grows a new body. The old body eventually dies instead of growing a new head.

The Deadpool slug is one of a type of sea slug that we talked about back in episode 129, about the blurry line between plants and animals. It eats algae and incorporates the algae’s chloroplasts into its body to use. Chloroplasts are what allows a plant to photosynthesize energy from sunlight, and the sea slug absolutely uses them for the same thing. Researchers think the Deadpool slug uses the energy from photosynthesis to regrow its body even though it has no digestive system after it separates its head from its body.

The big question is why the Deadpool slug wants to grow a new body in the first place. It doesn’t seem to be a defensive strategy if the sea slug is attacked. Instead, researchers think it often happens when the body contains too many parasites, specifically a type of tiny parasitic copepod, which is a crustacean. It might also happen after a predator bites a big chunk off the slug. Instead of hauling around a damaged body, the sea slug just jettisons the old body and regrows it.

Let’s finish with a recently solved octopus mystery that goes back almost 200 years. In 1838, the United States launched a scientific expedition throughout the Pacific Ocean and parts of the Atlantic that lasted four years. While it was mostly for exploration and mapping of places seldom or never visited by outsiders, the expedition also brought along a team of scientists and artists to document and study all the animals and plants they found. One of the things they found was an octopus.

The scientists didn’t fish the octopus up themselves. They actually bought several of them at a fish market in Brazil. It was red with little white spots all over it and not very big, although a dead octopus tends to shrink, especially when it’s out of water. The specimens were preserved in a jar of alcohol and brought back to the United States, where in 1852 they were studied by an expert on mollusks, Augustus Addison Gould. Octopuses are in the phylum Mollusca and Gould had examined lots and lots of octopuses. He decided this one was a new species and named it Callistoctopus furvus.

At some point the specimens were either lost or destroyed. Decades passed, then a century, then almost two centuries. Modern scientists thought Gould was probably wrong and that the little red octopus was one known from the Mediterranean Sea, Calistoctopus macropus. It’s red with little white spots, and has a mantle length only about 8 inches long, or 20 cm, although it has long arms and has been measured as almost five feet long, or 1.5 meters, if you include the arms. It lives in shallow water, where it spends a lot of time hunting for small animals that live in coral or in sea grass. It’s sometimes called the grass octopus.

Then a graduate student in Brazil named Manuella Dultra was studying octopuses, and part of her research involved talking to local fishers. They told her about an octopus that lived in shallow water and often buried itself in sand to hide, which is why they called it the sand octopus. They also said it was generally only seen when the wind blew from the east, and was more likely to be out and about during the new moon. Naturally Dultra wanted to find one. She asked the fishers to keep an eye out, and in 2013 she was given a freshly caught specimen.

The biologists at Dultra’s university identified the octopus as C. macropus, the grass octopus. Dultra wasn’t so sure. She noticed a lot of differences that seemed significant, and decided to do more research. She and her team gathered genetic material from specimens the local fishers caught, and sure enough, it was different from the grass octopus.

At the same time, researchers in Mexico had also found a sand octopus that they thought might be C. furvus. When Dultra compared her specimens’ DNA profile with the DNA profile from the Mexican octopus, it matched.

The discovery is still very new and isn’t accepted by all scientists yet, not until more studies are completed. The sand octopus appears to be rare, and once it’s definitely identified as its own species or subspecies and we learn more about it, we can do more to protect it.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. If you like the podcast and want to help us out, leave us a rating and review on Apple Podcasts or Podchaser, or just tell a friend. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us for as little as one dollar a month and get monthly bonus episodes.

Thanks for listening!