Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 11:54 — 13.3MB)

Thanks to Ezra and Leo for suggesting these two sea monsters this week! Happy Halloween!

Further reading:

Legend of Chessie alive, well in Maryland

Here be sea monsters: We have met Chessie and…is it us?

Not actually a kraken, probably:

Not actually Chessie but an atmospheric photo of a toy brontosaurus:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

Just a few days remain in October, so this is our Halloween episode and the end of monster month for another year! We had so many great suggestions for Halloween episodes that I couldn’t get to them all, but I might just sprinkle some in throughout the other months too. We have two great monsters to talk about this week, suggested by Ezra and Leo, the kraken and Chessie the sea serpent.

First, as always on our Halloween episode, we have a few housekeeping details. If anyone wants a sticker, feel free to email me and I’ll send you one, or more than one if you like. That offer is good all the time, not just now. I don’t have any new stickers printed but I do have lots of the little ones with the logo and the little ones with the capybara.

I also don’t have any new books out this year, but you can still buy the Beyond Bigfoot & Nessie book if you like. I am actually working on another book about mystery animals, tentatively titled Small Mysteries since it’s going to be all about mysteries surrounding small animals like frogs and invertebrates that often get overlooked. I’m hoping to have it ready to publish in early 2026 or so. I don’t know that I’ll do another Kickstarter for it since that was a lot of work, and I just finished a Kickstarter for more enamel pins and just can’t even think about the stress of doing another crowdfunding campaign anytime soon. Also, I hate to keep asking listeners for money.

Anyway, one of the things I don’t like about Beyond Bigfoot & Nessie is that I didn’t cite my sources properly, so for the Small Mysteries book I’m being very careful to have footnotes on pretty much every page so that anyone who wants to double-check my information can do so easily.

But all that is in the future. Let’s celebrate Halloween now with a couple of sea monsters!

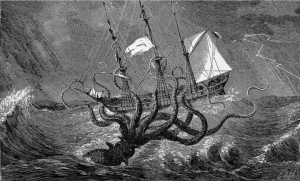

We’ll start with Ezra’s suggestion, the kraken. It’s a creature of folklore that has gotten confused with lots of other folklore monsters. We don’t know how old the original legend is, but the first mention of it in writing dates to 1700, when an Italian writer published a book about his travels to Scandinavia. One of the things he mentions is a giant fish with lots of horns and arms, which he called the “sciu-crak.” This seems to come from the Norwegian word meaning sea krake.

“Krake” is related to the English word crooked, and it can refer to an old dead tree with crooked branches, or tree roots, or something with a hook on the end like a boat hook, or an anchor or drag, or various similar things related to hooks or multiple prongs. That has led to people naturally assuming that the kraken had many arms and was probably a giant squid, and that may be the case. But there’s another possibility, because in many old uses of the word krake, it means something weak or misshapen, like a rotten old dead tree. In the olden days in Norway, people thought that if you spoke about an animal by name, the spirit that protected that animal would hear you. Some historians think that whale-hunters referred to whales as krake so the whale’s protective spirit wouldn’t guess that they were planning a whale-hunt. Who would refer to a huge, strong animal like a whale as weak and crooked, after all?

Whatever its origins, the kraken’s modern form is mainly due to a Danish bishop called Erik Pontoppidan. He wrote about the kraken in 1753, and embellished the story by saying the kraken could reach out of the ocean with its long arms to grab sailors or just pull an entire ship down into the water and sink it. He also said the kraken was so big that when it rested at the water’s surface, sailors would mistake it for an island. This is a common story in many cultures, always referring to whales. Pontoppidan suggested the kraken might be a giant octopus, but also thought it might be a giant starfish or even a giant crab. He seemed to think the word kraken should be krabben, and I swear I didn’t make that up.

Either way, the kraken is a monster of folklore, not a real animal. That’s a relief! Now you don’t have anything to worry about in the ocean at all, right?

Next, let’s learn about another water monster, Chessie, suggested by Leo. Leo also suggested we talk about Chesapeake Bay in general.

Chesapeake Bay is located on the east coast of North America, specifically where the states of Virginia, Maryland, and Delaware meet. On the map it looks sort of like a huge crack in the land, but while rivers and streams empty into it like they would a gigantic lake, it’s connected to the Atlantic Ocean. It’s about 200 miles long, or 320 km, and up to 30 miles wide, or 48 km.

It formed about 35 million years ago when a small meteor struck the area. During the Pleistocene, AKA the ice ages, the Susquehanna River flowed through the crater and into the sea. Around 10,000 years ago, ocean levels rose due to melting glaciers, and flooded the river valley that had started out as an impact crater. Now it’s a bay.

Chesapeake Bay isn’t technically a lake, but it’s also not really part of the ocean. Part of the bay is freshwater from the rivers that flow into it, while at the end that connects to the Atlantic Ocean, it’s salty. In between it’s brackish water that’s kind of salty but not nearly as salty as the ocean. It’s home to hundreds of animals, with many more visiting the bay during migration. Sometimes whales are even spotted in the bay.

We could literally talk about the animals and the history of Chesapeake Bay all day and not run out of topics, so I have plans to revisit some of the animals in future episodes. Today we mainly want to focus on the sea monster known as Chessie.

As you may have already guessed, the name Chessie isn’t just short for Chesapeake, it also echoes the name Nessie, the Loch Ness Monster. The first Nessie sighting was in 1933, leading to a lake monster craze in Scotland and many other parts of the world. Suddenly people were seeing monsters everywhere, such as Champ from Lake Champlain, which we talked about in episode 29 along with Nessie.

No one’s sure when the first Chessie sighting happened. Some people say it was as early as 1936, while others claim it wasn’t until 1980. In 1943 two fishermen reported seeing a strange creature in the water about 75 yards from their boat, or 68 meters. At first they thought there was something black floating in the water, with the visible part of it about 12 feet long, or 3 ½ meters. Then they realized it was alive. Its head was shaped like a horse’s but was only about the size of an American football. It’s not clear if it raised its head completely out of the water like a sea serpent in a cartoon, but the men did say that it turned its head almost all the way around several times.

There are also reports from 1977, 1978, 1980, 1982, 1997, and 2014. In 1978 a retired CIA officer saw what looked like a 15-foot, or 4 ½ meter, snake swimming in the water. In 1982 a man named Bob Frew took some grainy videocamera footage of something that he described as “a telephone pole that swims.” The video shows a brown object swimming like a marine snake, with a side to side motion.

In the 1980s people in the state of Maryland tried to get Chessie listed as a protected species. It didn’t work, but it did bring attention to the state of the Chesapeake Bay. The bay was increasingly polluted by industrial and agricultural waste that was allowed to enter the bay untreated, leading to algal blooms that deoxygenated the water and killed everything around them. The once-famous oyster reefs in the bay started to be overharvested too, and since oysters are natural water filters, their absence has caused an extra decrease in water quality. With Chessie acting as a mascot for water quality and ecology, people paid more attention to what was happening to the bay.

Chessie the monster doesn’t have a lot of sightings, and most likely they’re all misidentifications of ordinary animals or items, like whales or floating logs. There are some amazing creatures that live in or visit the bay, including a fish called the sturgeon that can grow up to 15 feet long, or 4.6 meters, bull sharks that can grow up to 13 feet long, or 4 meters, bottlenose dolphins, sea turtles, even manta rays. Most people agree that Chessie probably isn’t an actual sea serpent.

But there is another Chessie that’s definitely real, although you can’t actually call him a monster. A Florida manatee was spotted in the summer of 1994 swimming around in the bay and exploring some of the river mouths. Since Chesapeake Bay is nice and warm in summer, the manatee was fine at first. But by October he was still there, and the water was getting too cold for a manatee to tolerate.

Maryland’s Department of Natural Resources worked with the Coast Guard and a lot of volunteers to find the manatee, capture him safely, and get him back to Florida. He was given a clean bill of health by veterinarians and was tagged and released.

The following summer, he swam back to Chesapeake Bay. But who can blame him? It’s a beautiful place!

You can find Strange Animals Podcast at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us for as little as one dollar a month and get monthly bonus episodes.

Thanks for listening!