Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 11:44 — 13.0MB)

Thanks to Anbo and Siya for suggesting the mantis shrimp this week!

The Kickstarter for some animal-themed enamel pins is still going on!

Further reading:

Rolling with the punches: How mantis shrimp defend against high-speed strikes

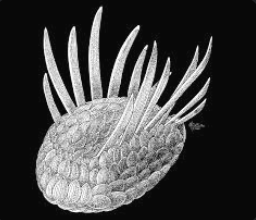

The magnificent peacock mantis shrimp [picture by Cédric Péneau, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=117431670]:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

As invertebrate August continues, this week we have a topic suggested by Anbo and Siya. They both wanted to learn about the mantis shrimp!

The mantis shrimp, which is properly called a stomatopod, is a crustacean that looks sort of like a lobster without the bulky front end, or a really big crayfish. Despite its name, it’s not a shrimp although it is related to shrimps, but it’s more closely related to lobsters and crabs. It can grow as much as 18 inches long, or 46 cm, but most are about half that size. Most are brown but there are hundreds of different species and some are various brighter colors like pink, blue, orange, red, or bright green, or a rainbow of colors and patterns.

There are two things almost everyone knows about the mantis shrimp. One, it can punch so hard with its claws that it breaks aquarium glass, and two, it has 12 to 16 types of photoreceptor cells compared to 3 that humans have, and therefore it must be able to see colors humans can’t possibly imagine.

One of those things is right, but one is wrong, or at least partially wrong. We’ll discuss both in a minute, but first let’s learn the basics about these fascinating animals.

The mantis shrimp lives in shallow water and spends most of its time in a burrow that it digs either in the sea floor or in crevices in rocks or coral, which it enlarges if necessary. Some species will dig elaborate tunnel systems while others just wedge themselves into any old crack that will hide them. It molts its exoskeleton periodically as it grows, like other crustaceans, and after that it either has to expand its burrow or move to a larger one. Most species live in tropical or subtropical areas, but some prefer more temperate waters.

It has eight pairs of legs, which includes three pairs of walking legs, four pairs with claws that help it grasp items, and its front pair, which are hinged and look a little like the front legs of a praying mantis. That’s where the “mantis” in mantis shrimp comes from, although of course it has lots of other names worldwide. In some places it’s called the thumb splitter.

The mantis shrimp has two eyes on stalks that move independently. Its brain extends into the eye stalks, and the section of the brain in the eye stalks, called the reniform body, is what processes vision. This allows it to process a lot of visual information very quickly. Reniform bodies have also been identified in the brains of some other crustaceans, including shrimp, crayfish, and some crabs. Scientists also think that the eyes themselves do a lot of visual processing before that information gets to the reniform body or the brain at all. In other words, part of the reason the mantis shrimp’s eyes are so complicated and so unusual compared to other animals’ eyes is because each eye is sort of a tiny additional brain that mainly processes color.

The typical human eye can only sense three wavelengths of light, which correspond to red, green, and blue. The mantis shrimp has twelve different photoreceptors instead of three, meaning it can sense twelve wavelengths of light, and some species have even more photoreceptors. But while our brains are really good at synthesizing the three wavelengths of light we can see, combining them so that we see incredibly fine gradations of color in between red, green, and blue, the mantis shrimp doesn’t process color the same way we do. So while its eyes can sense colors we can’t, its brain doesn’t seem to do anything with the color information. The eyes themselves process the colors to determine if an object is important or dangerous or food or whatever, and the determination of the object is the part that’s important to the brain, not what the actual color is.

Maybe by the year 2124, you can go into an eye clinic and have those extra sensors added to your eyes so you can see more colors, because a human brain knows exactly what to do with extra color information. We use it to make art.

Mantis shrimp can see ultraviolet light, which we talked about in episode 369. To be clear, we didn’t specifically talk about mantis shrimp in that episode, just UV light. At least six species of mantis shrimp can also see polarized light, with at least one species, the purple spot mantis shrimp, capable of dynamic polarization vision. (I don’t know what that means.) When sunlight reaches our earth’s atmosphere, the light waves are affected by earth’s magnetic field and the atmosphere itself. This scatters the light, causing it to travel in a sort of spiral. A lot of animals can sense light polarization, like bees and octopuses, which allows them to navigate more accurately. Mantis shrimp have patterns on their bodies that reflect polarized light in certain ways, so scientists think that’s one way mantis shrimp identify each other while staying hidden from most animals, which either can’t sense polarized light at all or can only sense it faintly.

So we must ask ourselves: If the mantis shrimp doesn’t use its multiple photoreceptors to see color, what does it use them for? We’re not fully sure yet, but scientists have some suggestions. The fertility of a female mantis shrimp depends on the tidal cycle, which is dependent on the phase of the moon, but if you live underwater and spend most of the time in a burrow, you can’t exactly look up at the moon easily or check how big the waves are. The female fluoresces when she’s fertile, though, and she fluoresces at a wavelength that the male can see but other animals can’t.

So it’s not completely accurate to say that the mantis shrimp can see colors we can’t even imagine, because there’s a difference in the eye seeing something and the brain processing it. But that means that the other mantis shrimp fact is completely true, that its claws are so strong that it can crack aquarium glass. But it’s more complicated than it sounds, because different mantis shrimp species have different abilities.

Mantis shrimp that hunt fish are called spearers, because the ends of their front pair of legs have a barbed spike that the mantis shrimp uses to spear the fish. Mantis shrimp that eat clams and other animals with hard shells are called smashers, and instead of spikes, the ends of their front pair of legs have a hammer-like club that the mantis shrimp uses to punch its prey. Both spearers and smashers can move their front legs incredibly fast, literally at the speed that a bullet leaves the barrel of a gun, with a correspondingly strong amount of force when the leg connects with something.

Moving the legs so fast also causes a small shock wave in the water, which can kill a small animal even if the mantis shrimp misses hitting it. The shock wave is actually what the mantis shrimp uses to smash the shells of clams and other hard-shelled prey, and it also uses the shock wave to smash pieces of coral or rock when it wants to enlarge its burrow. Its body has multiple layers of tissue that absorb the shock wave so it won’t damage the mantis shrimp itself.

Smashing or spearing so fast costs the mantis shrimp a lot of energy, so if it feels threatened by a potential predator it will spread its arms wide to look intimidating before it actually resorts to striking. That’s when it earns the name thumb splitter. That’s also the main reason why it isn’t very common for people to eat mantis shrimp even though they’re perfectly edible to humans and reportedly taste like lobster. They’re just too hard to catch and kill safely.

Some species of mantis shrimp mate for life, with some bonded pairs staying together for decades. Depending on the species, both parents take care of the eggs, or the female takes care of the eggs and the male brings her food. In one species, the female lays two bunches of eggs. She takes care of one bunch, while the male takes care of the other.

Many species of mantis shrimp are territorial, and if one enters another’s territory, the two may end up fighting. When you can punch as hard as a mantis shrimp, you need a good defense. During fights, the mantis shrimp coils its tail in front of its body to act as a shield. The tail is well armored, but the armor is layered to absorb and dissipate energy from punches.

The peacock mantis shrimp is the one that most people have heard about. It’s even one of the creatures you can catch in Animal Crossing by diving. It’s metallic green and blue with orange legs, purple eyes, and white spots, so some aquarium keepers love having one on display. The problem is that they will kill and eat pretty much anything else kept in the same tank, will smash up any rocks or coral in the tank too, and yes, they will even smash the aquarium glass—which is exceptionally strong in big aquariums, more like a car window than a window in your house. Sometimes an aquarium keeper will use a rock from the ocean to decorate the aquarium, and only find out too late that there’s a peacock mantis shrimp already living in a crevice in the rock. Then all they can do is take the rock back to the ocean, because getting a mantis shrimp out of its rock safely is pretty much impossible.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us for as little as one dollar a month and get monthly bonus episodes.

Thanks for listening!