Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 13:30 — 15.9MB)

Thanks to Richard from NC for inspiring this episode!

Further reading:

Paleontologists Debunk Popular Claim that Protoceratops Fossils Inspired Legend of Griffin

The Fossil Dragons of Lake Lucerne, Switzerland

The Lindworm statue:

A woolly rhinoceros skull:

A golden collar dated to the 4th century BCE, made by Greek artisans for the Scythians, discovered in Ukraine. The bottom row of figures shows griffins attacking horses:

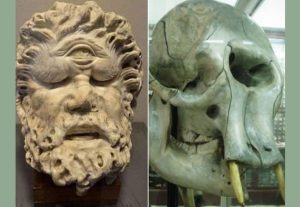

The Cyclops and a (damaged, polished) elephant skull:

A camahueto statue [photo by De Rjcastillo – Trabajo propio, CC BY 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=145434346]:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

This week we’re going to learn about the link between fossils and folklore, a topic inspired by a conversation I had with Richard from North Carolina.

We know that stories about monsters were sometimes inspired by fossils, and we even have an example from episode 53. That was way back in 2018, so let’s talk about it again.

In Klagenfurt in Austria there’s a statue of a dragon, called the lindorm or lindwurm, that was erected in 1593 to commemorate a local story. The story goes that a dragon lived near the lake and on foggy days would leap out of the fog and attack people. Sometimes people could hear its roaring over the noise of the river. Finally the duke had a tower built and filled it with brave knights. They fastened a barbed chain to a collar on a bull, and when the dragon came and swallowed the bull, the chain caught in its throat and tethered it to the tower. The knights came out and killed the dragon.

The original story probably dates to around the 12th century, but it was given new life in 1335 when a skull was found in a local gravel pit. It was clearly a dragon skull and in fact it’s still on display in a local museum. The monument’s artist based the shape of the dragon’s head on the skull. In 1935 the skull was identified as that of a woolly rhinoceros.

In 1989 a folklorist proposed that the legend of the griffin was inspired by protoceratops fossils. The griffin is a mythological creature that’s been depicted in art, writing, and folklore dating back at least 5,000 years, with early variations on the monster dating back as much as 8,000 years. The griffin these days is depicted as a mixture of a lion and an eagle. It has an eagle’s head, wings, and front legs, and it often has long ears, while the rest of its body is that of a lion.

The griffin isn’t a real animal and never was. It has six limbs, for one thing, four legs and two wings, and it also has a mixture of mammal and bird traits. I can confirm that it’s a lot of fun to draw, though, and lots of great stories and books have been written about it in modern times. Ancient depictions of a griffin-like monster have been found throughout much of eastern Europe, the Middle East, the Mediterranean, northern Africa, and central Asia. Much of what we know about the griffin legend comes from ancient Greek and Roman stories, but they in turn got at least some of their stories from ancient Scythia. That’s important for the hypothesis that the griffin legend was inspired by protoceratops fossils.

Protoceratops lived between 75 and 71 million years ago and its fossils have been found in parts of China and Mongolia. It was a ceratopsian but it didn’t belong to the family Ceratopsidae, which includes Triceratops. It grew up to about 8 feet long, or 2.5 meters, with a big skull and a neck frill, but while that sounds big, it actually was on the small size for a ceratopsian. At most it would have barely stood waist-high to an average human, so while it was heavy and compact, it was probably smaller, if not lighter, than a modern lion. It ate plants and while it had teeth, it also had a beak, sort of like a turtle’s beak.

Folklorist Adrienne Mayor published a number of papers and a book in the 1990s discussing the links between protoceratops fossils and the griffin legend. The fossils are fairly common in parts of Mongolia and China, and Mayor pointed out that the beak combined with four legs would have suggested a four-footed animal with a bird’s head. She suggested that the head frill might have been interpreted as wings.

As for the Scythians, which we talked about a few minutes ago, they were a nomadic people who ruled much of west and central Asia and part of eastern Europe up to about 300 BCE. They were skilled in metalworking and loved gold, so even though they didn’t have a system of writing, we have some of their metal artifacts found by archaeologists. The Scythians were so important to the ancient world that we know a lot about them from other cultures, especially the ancient Greeks, Persians, and Assyrians.

We know the griffin appeared in Scythian mythology because it’s depicted on some decorative metal items. We also have ancient stories about griffins loving gold and either battling people to steal gold, or mining gold that people stole from them, or some other variation. Scythians had elaborate trade routes that connected Asia and Europe, and as I mentioned, they were hugely influential. I mean, we’re still telling versions of monster stories that the Scythians probably came up with originally.

Mayor suggested that the Scythians found protoceratops fossils while prospecting for gold, thought they were the bones of the monster we now call a griffin, and spread stories about them throughout Eurasia. It sounds plausible, so much so that no one really investigated the story until recently.

Just last week as this episode goes live, a new study has been published by a team of paleontologists about the griffin-protoceratops connection. They worked with historians and archaeologists to determine when and where (and if) the Scythians might have discovered protoceratops fossils.

It turns out that they probably wouldn’t have, certainly not while prospecting or mining gold. Gold has never been found anywhere near protoceratops fossils, and in fact the known gold deposits in central Asia occur hundreds of kilometers away from the fossils found so far. Not only that, it would be very rare to find more than a little bit of fossilized bone sticking out of the rock in most cases.

The spread of the griffin in art doesn’t seem to have begun in central Asia, for that matter, and even the earliest artwork doesn’t seem to be very protoceratops-like. The head isn’t huge in comparison to the body, for instance. Early griffins were commonly depicted as lions with an eagle’s head, but sometimes they were depicted as eagles with a lion’s head.

That doesn’t mean that protoceratops fossils didn’t influence griffin mythology at some point, just that it didn’t seem to happen the way Mayor claimed it did.

Another common connection between a fossil and a mythical monster is likewise just speculation. The skulls of elephants and their ancestors have a big opening in the front that looks like a giant eyesocket, but which is where the trunk was located. The eyes are much smaller and more on the sides of the head, and the skull itself does somewhat resemble a really big human skull. The Cyclops, or Cyclopes, was a giant from ancient Greek myth with one eye in the middle of its face instead of the usual two eyes. Is there really a connection between some kind of elephant skull and the Cyclops?

The connection was first suggested in 1914 by a paleontologist named Othenio Abel, who suggested that skulls from dwarf elephants had inspired the myth. Before about 500 BCE, the ancient Greeks didn’t know what elephants were, and the dwarf elephants that once lived in the area went extinct about 20,000 years ago. Sicily and Malta in particular had been home to various species of dwarf elephant for half a million years, so it’s possible that elephant remains were occasionally discovered in the area. Our griffin-protoceratops friend Adrienne Mayor agrees, but there’s no proof either way of this happening.

Stories of dragons living on Mount Pilatus in Switzerland may have been inspired by the pterosaur fossils that are frequently found in the area. In 1649 a man named Christopher Schorer reported seeing a fiery dragon fly from a cave in the side of Mount Pilatus to another mountain, although he admitted that at first he thought it was a meteor. It was probably a meteor, in fact, but he convinced himself it had to be a dragon because they were known to live on the mountain. A so-called dragon skeleton found near the mountain in 1602 had reportedly been crushed flat by rocks during an earthquake, but once science caught up with the finding, it was determined to be a fossilized pterodactyl.

In many parts of the world, especially China, fossilized bones are called dragon bones, but the dragon as a mythological creature probably came first. This is probably the case for a lot of folklore monsters and animals. The story came first, and once fossils were found in the area, they were seen as proof that the story was true.

In Patagonia in South America, there’s a Chilote legend of a monster called the camahueto. When it’s grown it lives in the ocean, but it starts out life living underground. Eventually it picks a stormy night, and it emerges from the ground and rushes toward the ocean, destroying everything in its path. Its single horn may gouge a channel in the ground for a new stream to form, or it may actually live in a river as a young animal and migrate to the ocean as an adult.

An animal named Trigodon once lived in Patagonia. It was a notoungulate, part of an extinct order of hoofed animals that lived throughout South America. It was probably most closely related to rhinoceroses, horses, and other odd-toed ungulates, but it and its relatives are completely extinct with no living descendants.

Trigodon was big and heavy, probably resembling a rhinoceros in many ways, and that includes having a single short horn on its head. On its forehead, in fact, pointing straight forward. It probably wasn’t a true horn but it was a protuberance of the skull. We don’t know if it was covered with skin and hair like an ossicone, a keratin sheath like a true horn, or if it was more like a rhinoceros horn. It might have been something completely different that’s currently unknown among living animals.

Trigodon went extinct around 4 million years ago, as far as we know, but other notoungulates only went extinct around 12,000 years ago. We don’t know very much about most of them, but we do know that at least one other species had a forehead horn like Trigodon’s. It’s always possible that a rhinoceros-like one-horned animal was still alive when humans first settled Patagonia, and that it was so big and scary it inspired stories about the monster Camahueto, a bull with a single horn on its forehead.

Then again, consider the story about the camahueto. It lives underground or in rivers when it’s young, and travels to the sea only during a storm. That might just be a story used to explain earthquakes that open fissures in the ground, and other natural phenomena. Then again, it might have been inspired by fossilized trigodon skulls that are washed out of the ground by torrential rain or rivers. That’s just my theory, though, but it’s fun to speculate.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us for as little as one dollar a month and get monthly bonus episodes.

Thanks for listening!